Which African Countries are at Risk from the Current Market Turmoil?

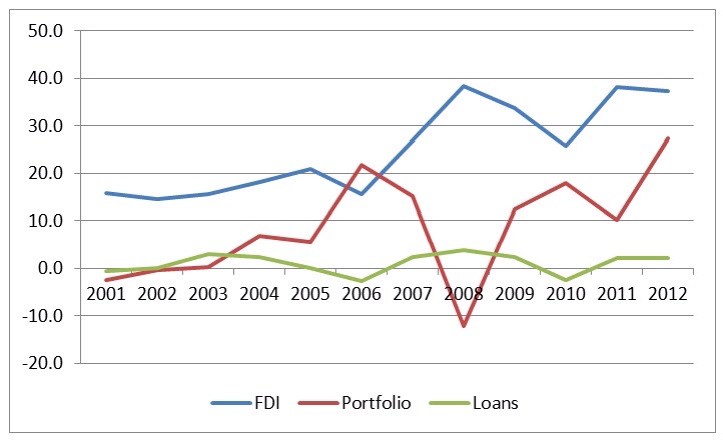

A few years ago, an analysis of the spillover effects of financial shocks on African countries would have only included South Africa. Given the relatively less-developed state of their capital markets, most African countries were not able to attract portfolio flows. Instead, they depended mostly on foreign direct investment  flows to complement their domestic revenues. However, this picture has changed, and a number of countries such as Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria are becoming increasingly connected to global financial markets (Figure 1). Foreign investors have started investing in African domestic bond and stock markets, and in dollar-denominated sovereign bonds issued by African countries. Portfolio investments, however, can be reversed quickly and, in the process, generate market volatility. At the moment, South Africa, Ghana and, to some extent, Nigeria are the African countries most at risk from the current market turmoil.

flows to complement their domestic revenues. However, this picture has changed, and a number of countries such as Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria are becoming increasingly connected to global financial markets (Figure 1). Foreign investors have started investing in African domestic bond and stock markets, and in dollar-denominated sovereign bonds issued by African countries. Portfolio investments, however, can be reversed quickly and, in the process, generate market volatility. At the moment, South Africa, Ghana and, to some extent, Nigeria are the African countries most at risk from the current market turmoil.

Indeed, emerging markets are experiencing a bout of volatility reminiscent of the pre-1998 Asian crisis period. The trailer of this movie was launched last May when market participants were unnerved by Chairman Ben Bernanke’s mention of the possibility of the Federal Reserve tapering its securities purchases, thereby raising interest rates. This time, signs of a slowdown in Chinese growth have exacerbated market anxiousness about the Fed tapering.

One explanation for the current market turmoil is that market participants that have poured money into these countries when U.S. interest rates were low are now finding them less attractive as U.S. interest rates are rising, and the appetite for riskier investments is decreasing. The least attractive countries will be the most affected and as investors exit and sell their assets, the currencies and financial markets of these countries will take a beating.

Now what is deemed “less attractive” by market participants is debatable. And, for each seller, you need a buyer. But it is clear that investors are scrutinizing the fundamentals of the so-called “Fragile Five” countries—Brazil, India, Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa. These countries are labeled as fragile because they have weaker fundamentals than other countries. Fundamentals can include fiscal and current-account deficits (or a combination of the two), falling GDP growth rates, above-target inflation, and political uncertainty from upcoming elections. Worse, other countries such as Argentina, Venezuela, Ukraine, Hungary and Thailand are being added to the list of vulnerable countries.

One way to identify the other African countries most at risk is to check where the current episode of volatility in emerging markets is being mirrored in domestic equity and bond markets as well as in currency markets.

Domestic stock markets suffer when foreign investors exit. The MSCI Frontier Market indices (which foreign investors monitor) show that returns from Ghanaian equity investments have dropped from a whopping 56 percent annualized return last year to 4 percent since January. In South Africa, Kenya and Nigeria, stock market returns have turned negative, erasing more than last year’s gains (Figure 2). The performance of these equity markets is not surprising, as all these countries have been receiving significant portfolio inflows in their local securities markets.

Volatility on global markets can also spill over to African bond markets. Although it is difficult to obtain historical data on local currency bonds, data on nonresident holdings of domestic debt indicate that Nigeria, Ghana and South Africa are the most vulnerable countries to portfolio reallocation by foreign investors. In these three countries, at least one investor out of five is a nonresident. Interestingly, Kenya’s domestic bond market does not rely much on foreign investors.

The maturity of the domestic debt held by foreign investors matters a lot as short-term debt has to be rolled over more frequently and in periods of stress, at a much higher cost. The foreign currency- denominated bond markets seem to be less of a problem for now, as no eurobond issued by sub-Saharan country matures before 2017, according to Fitch Ratings. However, for those countries—such as Ghana—that plan to issue bonds, higher costs are to be expected.

When it comes to currency markets, South Africa, Ghana, and, to some extent, Nigeria clearly stand out.

Market participants have labeled South Africa as one of the Fragile Five, and the rand has plunged to a five-year low (of 11.39 rand per dollar) after falling 5.7 percent since January. Citing rising inflation, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) raised interest rates by 50 basis points to 5.5 percent, and South African Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan complained that markets were “overshooting.” In his defense, it is well-known that market participants tend to exit quickly from South Africa’s financial markets because they are very liquid. In periods of stress, it is just faster to liquidate assets held in Johannesburg than in many other emerging markets.

The Ghanaian cedi has already dropped 3.8 percent in the first five weeks of the year. Ghana’s troubles are not new but they are a sign of its fragility. Last year, the cedi lost 19 percent of its value and the sovereign rating was downgraded (by one level to B) by Fitch Ratings. The inflation rate of 13.5 percent has almost reached its four-year high. Ghana has both a current account and external deficits, and is having difficulties meeting its target budget deficit of 8.5 percent of GDP (it reached 10.2 percent in 2013). To put simply, the country imports more than it exports, and the government spends more than it can raise through taxes. To finance these gaps, Ghana has had to rely on foreign financing. As a result, increasing foreign money came in the domestic bond and stock markets. Now that some of the foreign money is being repatriated or coming at a much reduced place, the currency loses its value. If Ghanaian firms start losing confidence and start asking for more foreign currency, then the fall of the cedi will accelerate.

Nigeria’s currency has been less volatile in part because of administrative and other measures. The naira weakened to its lowest level since September last year after the central bank removed the limit that may be sold to a bureau de change.

What can African countries do?

It is useful to separate the problem into two related issues: policies to address the current short-term volatility and those that target long-term measures.

South Africa has a lot of experience dealing with the type of volatility it is experiencing now. The recent interest rate hike by SARB actually surprised many observers and had a very limited impact on the falling rand. The rand is left floating (it has reached a five-year low) precisely to serve as a shock absorber.

In contrast, in an effort to limit the fall of the cedi, the Ghanaian central bank imposed limits on foreign-exchange transactions, and ordered sales and purchases made within the country to be done in local currency. It then increased interest rates by two percentage points, to 18 percent.

Whether these measures will work or not is an empirical question but administrative controls can be circumvented (trust people’s imagination), and there is a limit to how much interest rates can be increased.

The Bank of Ghana faces a tough trade-off. On the one hand, “too high” interest rates can hurt the economy. For instance, if borrowing costs increase, local entrepreneurs will find fewer and fewer profitable projects, and may even postpone planned projects. They would hire less people, pay fewer taxes and may even go bankrupt—which would lead to portfolio losses in the banking sector. On the other hand, Ghana remains dependent on foreign savings, and investors there need to be compensated for the risk they rightly or wrongly perceive to be taking. Higher interest rates, in principle, help attract or at least retain foreign investments, but this is not always the case.

Portfolio flows can have benefits when they channel foreign savings to growth-enhancing investments. But the current market turbulence is a reminder that they also carry risks. African countries will have to manage these risks as they become increasingly linked to the global economy. Managing such risks requires adequate macroeconomic policies as well as sound financial supervision and regulation. The 1998 Asian crisis has shown the importance of avoiding the so-called balance sheet mismatches where the government, banks or even corporates rely too much on short-term foreign currency-denominated debt. Opening up domestic markets to foreign investors before building the proper institutional capacity to deal with these risks can be very costly.

But beyond measures to deal with the current market turbulence, structural measures can help reduce the fragility of African economies. For instance, South Africa needs to reduce its high level of youth unemployment and Ghana needs to diversify its economy. As Sri Mulyani Indrawati, the former minister of finance of Indonesia, puts it, “Surviving the crisis is one thing; emerging as a winner is something else entirely.”