Morocco will let private capital take the lead in developing desalination and irrigation projects as part of a $27 billion plan designed to lessen the stress on its water resources, Minister Charafat Afilal said.

The National Water Plan provides for an additional 5 billion cubic meters in water resources by 2030, as much volume as what flows over Niagara Falls in 24 days, the water minister said in an interview at her office in Rabat.

“The plan aims to address an expected rise in the national water deficit from 3 billion to 5 billion cubic meters in 2030,” Afilal said Sept. 19. The investment will maintain Morocco’s annual average for water availability at its current 700 cubic meters per capita as the population increases.

“Morocco has always had a water deficit, which explains how aquifers have been subject to abuse over the last few years,” said Afilal, a hydraulics engineer and one of five women in the 39-member cabinet of Islamist Prime Minister Abdelilah Benkirane.

The plan, whose cost is almost twice the total public investment budgeted for 2014, will rely mostly for financing on long-term concessions open to private operators.

Wasteful irrigation practices have been blamed for some inefficiencies and loss in the country’s agricultural industry.

“The government will raise the amount of its annual contribution to the water sector but operators will be shouldering a greater proportion of the costs incurred under this plan, whether it’s the investment or the running cost of the facilities they develop,” Afilal said.

‘Pay for Water’

Consumers “should pay for the water they use,” she said.

The government subsidizes the cost of drinking water by 2.3-2.5 dirhams per cubic meter but only for households whose monthly consumption is less than six cubic meters.

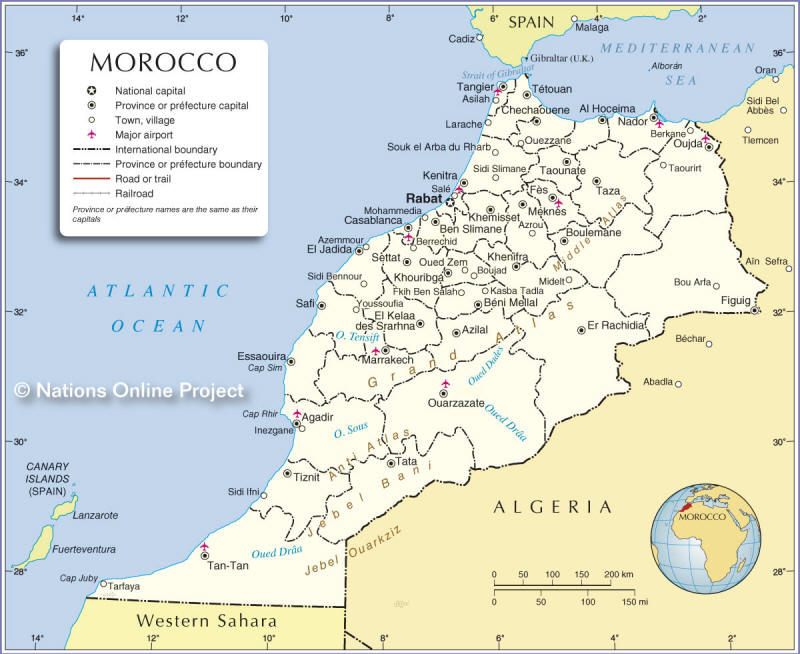

The subsidy is above what some regional independent utilities, such as in the resort of Marrakesh, charge households for up to 8 cubic meters but barely covers two-thirds the tariff in the drier eastern city of Oujda.

Morocco, where tourism has doubled since 2000, is prone to drought and heavily dependent on rainfall. Its agricultural industry employs almost 40 percent of the 11 million workforce. Pressure on water resources in such places as Marrakesh led to clashes in 2012 over rising costs.

“The water plan was elaborated in close cooperation with the agriculture department, which accounts for 80-90 percent of total water usage in Morocco. They agree on the need to shift to less thirsty crops but there is also a need to revamp the predominantly wasteful irrigation systems,” Afilal said.

No Watermelons

The growing of watermelons for instance was banned last week in the southern desert region of Zagora by her department and the agriculture ministry after aquifers fell to such levels it affected the salinity and quality of the water, she said.

Half of the 5 billion cubic meters Morocco hopes to gain from the plan will be through economies in consumption mostly by modernizing agricultural irrigation systems.

“The scope for broadening the use of drip irrigation is huge in Morocco where farming irrigation is generally traditional and wasteful,” she said.

The other 2.5 billion cubic meters will come from a half-dozen new desalination plants in build-operate-transfer partnerships between private operators and the state utility Office National de l’Eau et l’Electricite.

ONEE, which hitherto dominated the production of drinking water, signed a partnership in June for the first of the desalination plants with a consortium that includes Abengoa SA (ABG) of Spain and InfraMaroc, an affiliate of Rabat-based Caisse de Depot et de Gestion, Morocco’s biggest pension fund.

The agreement allows the group for 20 years to sell to ONEE the water it produces from a 100,000-cubic-meter a day desalination unit near Agadir it’s building.

North-South Canal

Another major project is a north-south waterway that Afilal said may carry 800 million cubic meters of water each year from the wetter north mostly to Casablanca, the biggest city and industrial center, as well as farming areas in the Rhamna region.

“It will cost 30 billion dirhams. We had a preliminary study and are currently in the phase of detailed studies which can take up to five years,” Afilal said.

Prime Minister Benkirane has described the canal project as “huge and strategic” and said once completed it would exempt Morocco from the need to import wheat.