South Africans endure up to three power outages a day as its electricity company, Eskom, struggles to cope

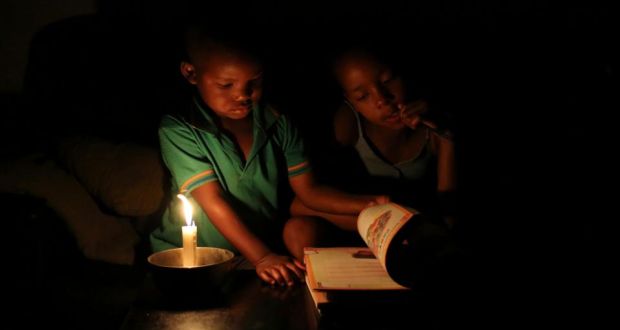

Studying by candle light during load shedding in Soweto. Photograph: Siphiwe Sibeko/Reuters

Studying by candle light during load shedding in Soweto. Photograph: Siphiwe Sibeko/Reuters

Rolling periodic power cuts known as load-shedding have been implemented across the country since mid-January by Eskom – the public electricity utility – to reduce the pressure on the national power grid so that essential maintenance can be carried out on its aging power generators.

Eskom chief executive Tshediso Matona said last month that the need to carry out maintenance at the power utility was so great, power station units had to be shut down to accommodate repairs and prevent a plant’s complete collapse.

“It is not whether or not load-shedding will be part of our lives, but how we are going to cope with it,” Mr Matona said during a January 15th press conference before adding that daily load-shedding would begin within one week.

Stage one load-shedding allows for up to 1,000 megawatts of the national load to be shed, stage two for up to 2,000 megawatts, and stage three for up to 4,000 megawatts.

Each power outage lasts a minimum four-hour period and affected areas can be subjected to two or three outages a day depending on the stage being implemented.

Since South Africa last experienced load-shedding of this magnitude, in 2008, Eskom has been putting off essential maintenance and keeping the lights on by running open cycle gas turbines on diesel. But Mr Matona admitted: “Our equipment is so unreliable and the risk of breakdown has become so high . . . that it has created havoc for us”.

To make matters worse, the availability of energy plants has also fallen over the past six years from 85 per cent to 75 per cent because the quality of maintenance has deteriorated on the power generators, 64 per cent of which are past their mid-life.

Price hikes

Eskom is also in serious financial crisis and further significant electricity price hikes are a near certainty, even as customers increasingly find themselves sitting in the dark.

Eskom is one of the leading utilities in the world and has 27 operational power stations including one nuclear plant. It claims to generate over 95 per cent of the electricity used in South Africa and around 45 per cent of all electricity consumed across the African continent.

Due to the company’s importance to the continent’s economic growth, the questions on everyone’s lips are how have the government and Eskom ended up in this position, and how bad could this energy crisis really get?

According to its 2007 annual report, Eskom needs to nearly double its generation volume from its current maximum self-generated capacity of 41,194 megawatts to 80,000 megawatts by 2025.

To meet the country’s immediate demand shortfall, it is constructing two coal-fired nuclear power stations, Kusile and Medupi, which will contribute 9,000 megawatts of power to the national power per year.

While Eskom has said load-shedding will be with the country for a few years, many energy experts – as well as the main political opposition parties – warn this is an extremely optimistic forecast. They are warning that the current situation of rolling blackouts could be a reality for much longer than that, a factor that could scare off international investors, hamper business development and stifle job creation efforts.

According to the International Monitory Fund, South Africa needs an economic growth rate of at least 3 per cent annually to create jobs, but even this will only facilitation a reduction in the official unemployment rate of around 23 per cent if the labour force remains stagnant.

South Africa has estimated that GDP for the first nine months of 2014 increased by just 1.5 per cent com pared with the corresponding period in 2013, and this was before load-shedding had even been introduced.

The adverse effect that load-shedding is having on the economy in monetary terms was brought sharply into focus by South African energy specialist Chris Yelland.

Last week he was widely quoted in local media as saying that stage one load-shedding was costing the economy 20 billion rand (€1.5 billion) per month, with stage two forecast to carry a 40 billion rand monthly bill and stage three a massive 80 billion rand per month.

As a result of the crisis’s economic ramifications, it has become a political minefield for the ruling African National Congress party.

While the former liberation movement is still the dominant political force in South Africa, it has been losing support steadily for the past five or six years. It is clearly concerned at how rolling blackouts will affect its local election chances next year and beyond.

Passing phase

To try and deflect the culpability for the crisis away from itself, government has gone to great lengths to blame bad planning by successive apartheid-era governments for causing the situation. At the recent World Economic Forum President Jacob Zuma said: “Our electricity infrastructure was never designed to serve an expanded citizenry. Last year, we celebrated the expansion of electricity to 11-million households. In the last six months of the year, we reached more than 100,000 homes.

“This extension of electricity to more households that had been excluded in the past, coupled with a growing economy, has sharply put pressure on the infrastructure, which needs improved maintenance and expansion,” Mr Zuma said.

He went on to say the energy crisis was just a passing phase as the government had its new coal power stations and other sources of energy such as large-scale nuclear, shale gas, solar and wind plants in the pipeline to resolve this situation.

Mr Zuma’s government has insisted that the launch of the Medupi nuclear power station at the end of this year will help plug the current gap, as it has six power generating units that can produce 800 megawatts of electricity each.

However, only one of the units will come online at that time, and all six are not expected to contribute to the national grid before 2018.

Furthermore, Kusile nuclear power station is not expected to start coming online until 2016 at the earliest.

The opposition Democratic Alliance (DA) party maintains that Eskom itself is the main cause of the country’s unstable power supply, as it enjoy an unhealthy market monopoly because it controlled access to the national grid.

Earlier this month, DA leader Helen Zille questioned why the government appeared unwilling to break Eskom’s stranglehold over the market, saying it is not healthy for the same company that produces the bulk of the power, to also make decisions on transmission and grid expansion.

“Opening the grid, in a meaningful way, to independent power producers is key to solving our electricity generation shortfall,” she said. “There is certainly no shortage of project proposals for co-generation, and with every round of bidding, the cost has come down.”