The past has a disconcerting habit of bursting, uninvited and unwelcome, into the present. This year history gate-crashed modern America in the form of a 150-year-old document: a few sheets of paper that compelled Hollywood actor Ben Affleck to issue a public apology and forced the highly regarded US public service broadcaster PBS to launch an internal investigation.

The document, which emerged during the production of Finding Your Roots, a celebrity genealogy show, is neither unique nor unusual. It is one of thousands that record the primal wound of the American republic – slavery. It lists the names of 24 slaves, men and women, who in 1858 were owned by Benjamin L Cole, Affleck’s great-great-great-grandfather. When this uncomfortable fact came to light, Affleck asked the show’s producers to conceal his family’s links to slavery. Internal emails discussing the programme were later published by WikiLeaks, forcing Affleck to admit in a Facebook post: “I didn’t want any television show about my family to include a guy who owned slaves. I was embarrassed.”

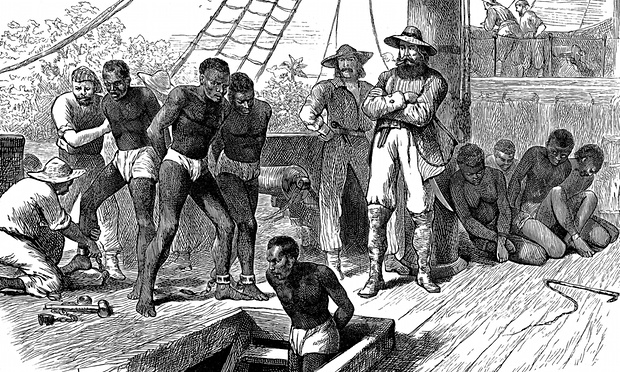

It was precisely because slaves were reduced to property that they appear so regularly in historic documents, both in the US and in Britain. As property, slaves were listed in plantation accounts and itemised in inventories. They were recorded for tax reasons and detailed alongside other transferable goods on the pages of thousands of wills. Few historical documents cut to the reality of slavery more than lists of names written alongside monetary values. It is now almost two decades since I had my first encounter with British plantation records, and I still feel a surge of emotion when I come across entries for slave children who, at only a few months old, have been ascribed a value in sterling; the sale of children and the separation of families was among the most bitterly resented aspects of an inhuman system.

Slavery resurfaces in America regularly. The disadvantage and discrimination that disfigures the lives and limits the life chances of so many African-Americans is the bitter legacy of the slave system and the racism that underwrote and outlasted it. Britain, by contrast, has been far more successful at covering up its slave-owning and slave-trading past. Whereas the cotton plantations of the American south were established on the soil of the continental United States, British slavery took place 3,000 miles away in the Caribbean.

That geographic distance made it possible for slavery to be largely airbrushed out of British history, following the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. Many of us today have a more vivid image of American slavery than we have of life as it was for British-owned slaves on the plantations of the Caribbean. The word slavery is more likely to conjure up images of Alabama cotton fields and whitewashed plantation houses, of Roots, Gone With The Wind and 12 Years A Slave, than images of Jamaica or Barbados in the 18th century. This is not an accident.

The history of British slavery has been buried. The thousands of British families who grew rich on the slave trade, or from the sale of slave-produced sugar, in the 17th and 18th centuries, brushed those uncomfortable chapters of their dynastic stories under the carpet. Today, across the country, heritage plaques on Georgian townhouses describe former slave traders as “West India merchants”, while slave owners are hidden behind the equally euphemistic term “West India planter”. Thousands of biographies written in celebration of notable 17th and 18th-century Britons have reduced their ownership of human beings to the footnotes, or else expunged such unpleasant details altogether. The Dictionary of National Biography has been especially culpable in this respect. Few acts of collective forgetting have been as thorough and as successful as the erasing of slavery from the Britain’s “island story”. If it was geography that made this great forgetting possible, what completed the disappearing act was our collective fixation with the one redemptive chapter in the whole story. William Wilberforce and the abolitionist crusade, first against the slave trade and then slavery itself, has become a figleaf behind which the larger, longer and darker history of slavery has been concealed.

It is still the case that Wilberforce remains the only household name of a history that begins during the reign of Elizabeth I and ends in the 1830s. There is no slave trader or slave owner, and certainly no enslaved person, who can compete with Wilberforce when it comes to name recognition. Little surprise then that when, in 2007, we marked the bicentenary of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, the only feature film to emerge from the commemoration was Amazing Grace, a Wilberforce biopic.

George Orwell once likened Britain to a wealthy family that maintains a guilty silence about the sources of its wealth. Orwell, whose real name was Eric Blair, had seen that conspiracy of silence at close quarters. His father, Richard W Blair, was a civil servant who oversaw the production of opium on plantations near the Indian-Nepalese border and supervised the export of that lethal crop to China. The department for which the elder Blair worked was called, unashamedly, the opium department. However, the Blair family fortune – which had been largely squandered by the time Eric was born – stemmed from their investments in plantations far from India.

The Blair name is one of thousands that appear in a collection of documents held at the National Archives in Kew that have the potential to do to Britain what the hackers of WikiLeaks and the researchers of PBS did to Affleck. The T71 files consist of 1,631 volumes of leather-bound ledgers and neatly tied bundles of letters that have lain in the archives for 180 years, for the most part unexamined. They are the records and the correspondence of the Slave Compensation Commission.

The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 formally freed 800,000 Africans who were then the legal property of Britain’s slave owners. What is less well known is that the same act contained a provision for the financial compensation of the owners of those slaves, by the British taxpayer, for the loss of their “property”. The compensation commission was the government body established to evaluate the claims of the slave owners and administer the distribution of the £20m the government had set aside to pay them off. That sum represented 40% of the total government expenditure for 1834. It is the modern equivalent of between £16bn and £17bn.

The compensation of Britain’s 46,000 slave owners was the largest bailout in British history until the bailout of the banks in 2009. Not only did the slaves receive nothing, under another clause of the act they were compelled to provide 45 hours of unpaid labour each week for their former masters, for a further four years after their supposed liberation. In effect, the enslaved paid part of the bill for their own manumission.

The records of the Slave Compensation Commission are an unintended byproduct of the scheme. They represent a near complete census of British slavery as it was on 1 August, 1834, the day the system ended. For that one day we have a full list of Britain’s slave owners. All of them. The T71s tell us how many slaves each of them owned, where those slaves lived and toiled, and how much compensation the owners received for them. Although the existence of the T71s was never a secret, it was not until 2010 that a team from University College London began to systematically analyse them. The Legacies of British Slave-ownership project, which is still continuing, is led by Professor Catherine Hall and Dr Nick Draper, and the picture of slave ownership that has emerged from their work is not what anyone was expecting.

The large slave owners, the men of the “West India interest”, who owned huge estates from which they drew vast fortunes, appear in the files of the commission. The man who received the most money from the state was John Gladstone, the father of Victorian prime minister William Ewart Gladstone. He was paid £106,769 in compensation for the 2,508 slaves he owned across nine plantations, the modern equivalent of about £80m. Given such an investment, it is perhaps not surprising that William Gladstone’s maiden speech in parliament was in defence of slavery.

The records show that for the 218 men and women he regarded as his property, Charles Blair, the great-grandfather of George Orwell, was paid the more modest sum of £4,442 – the modern equivalent of about £3m. There are other famous names hidden within the records. Ancestors of the novelist Graham Greene, the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and the architect Sir George Gilbert Scott all received compensation for slaves. As did a distant ancestor of David Cameron. But what is most significant is the revelation of the smaller-scale slave owners.

Slave ownership, it appears, was far more common than has previously been presumed. Many of these middle-class slave owners had just a few slaves, possessed no land in the Caribbean and rented their slaves out to landowners, in work gangs.These bit-players were home county vicars, iron manufacturers from the Midlands and lots and lots of widows. About 40% of the slave owners living in the colonies were women. Then, as now, women tended to outlive their husbands and simply inherited human property through their partner’s wills.

The geographic spread of the slave owners who were resident in Britain in 1834 was almost as unexpected as the gender breakdown. Slavery was once thought of as an activity largely limited to the ports from which the ships of the triangular trade set sail; Bristol, London, Liverpool and Glasgow. Yet there were slave owners across the country, from Cornwall to the Orkneys. In proportion to population, the highest rates of slave ownership are found in Scotland.

The T71 files have been converted into an online database; a free, publicly available resource.

During the production of a documentary series about Britain’s slave owners for the BBC, made in partnership with UCL, all of my colleagues who learned of the existence of the database found themselves compelled to enter their own family names. Those whose surnames flashed up on screen experienced, like Ben Affleck, a strange sense of embarrassment, irrespective of whether the slave owners in question were potentially ancestors.

There are, however, millions of people, in the Caribbean and the UK, who do not need a database to tell them that they are linked to Britain’s hidden slave-owning past. The descendants of the enslaved carry the same English surnames that appear in the ledgers of the Slave Compensation Commission – Gladstone, Beckford, Hibbert, Blair, etc – names that were imposed on their ancestors, initials that were sometimes branded on their skin, in order to mark them as items of property.

Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners, the first of two episodes, presented by David Olusoga, will be broadcast on Wednesday on BBC2. Click here for the Legacies of British Slave Ownership Database

FRENCH VERSION