On the 63rd anniversary of the 23 July 1952 revolution, Ahram Online revisits classic films that attempted to capture changes in the socio-political system

Adham Youssef,

In analysing films, one can always understand how the masses thought, and how filmmakers read between the lines, at the time a flick was produced.

This holds very true as far as Egyptian cinema goes.

Pre-1952 cinema: Awaiting Lashin

Egyptian cinema had already started reflecting the ‘historic moment’ very well years before the 23 July 1952 Revolution, when the Free Officers Movement – lead by Mohamed Naguib and Gamal Abdel-Nasser – overthrew Egypt’s King Farouq, ending over a century and half of monarchy and paving the way for independence from 80 years of British colonial rule.

As early as 1938, Lashin, one of Studio Misr’s earlier productions, tackled despotism using the ‘conflict of classes approach.’

Directed and co-authored by German filmmaker Fritz Kramp, the revolutionary film thrives on simple representation of the class struggle between the impoverished, who see the army commander Lashin as their Messiah, and the tyrants embodied by a king and his companions.

The film’s protagonist, a jailed Lashin, becomes the nucleus of rebellious thoughts.

However, Lashin was censored since Kramp dared to shoot it during the king’s reign.

Following the revolution other productions attempted to shed light on political corruption, autocracy, collaboration with the British, unveiling the immense gap between classes.

Films such as Salah Abu Seif’s El-Qahira 30 (Cairo 30) in 1966 and Henri Barakat’s Fi Baytona Ragol (A Man in Our Home) in 1962 deconstructed the past while providing context for the revolution.

El-Qahira 30 strikes at pre-1952 corrupt governments, elitist parties, repressive police apparatus, and the protagonists’ materialistic needs which push them to the abyss.

The 1960 Bedaya wa Nihaya (A Beginning and an End), also by Abu Seif, argued that the corruption of the rich is the root of more misery for the poor.

The Philosophy of the Revolution

Indeed after the revolution, filmmakers presented a nationalist narrative and protagonists full of heroism and sacrifice to the masses.

And what better way to cloak these ideals than a love story.

The 1957 Rudda Qalby (Give Me My Heart Back) directed by Ezzeldin Zulfikar is a story of the lower class peasants and professionals who were able to join the aristocrats-only military academy to end up rising to power as part of the anti-monarchists in the July revolution.

The officer in the film, played by Shukri Sarhan, not only seeks to eliminate differences between himself – and his poor background – and the feudalistic family of his beloved, but also avenge his fallen comrades who fell in the 1948 war to save Palestine due to the ‘betrayal of the monarchy.’

A closer look into Rudda Qalby reveals, in a way, a romanticised biography of Abdel-Nasser.

The 1955 Allah Maena (God Be With Us), starring Faten Hamama, tackles the angle of officers’ fury following the 1948 defeat.

Here, the film’s director, Ahmed Badrakhan, repeats the same points as those tackled by Zulfikar in Rudda Qalby.

Allah Maena was dropped from circulation in months, perhaps because Badrakhan cast the protagonist – an anti-monarchy army officer – as an older and high ranking general, not a young and mid-ranked officer, a fact which lead the masses to think of an older Naguib (by-now the under house arrest ex-real-life protagonist of 1952) not the younger Nasser who took control of all powers in ral life in 1954.

The film was quickly, and conveniently, ‘forgotten’ by decision makers, and disappeared from theatres soon after its release.

Having forced Naguib to resign from the presidency and placing him under house arrest, the new president Nasser succeeded in his quest for unchallenged powers, and began introducing a whole new social and political regime in the country. And, of course, he needed artists and intellectuals to help show the masses what life looked like in the new society.

Actors in the 1964 film Al-Aydi Al-Naema (The Soft Hands) resemble protagonists on Soviet socialist-realism propaganda posters: healthy, challenging, and nationalist. Directed by Mahmoud Zulfikar and starring Ahmed Mazhar, the film argues how Nasser eliminated, or at least minimised, the differences between the old aristocrats and the new middle classes.

More feminist representation of the same goals and themes is found in the 1966 Merati Modeer Aam (My Wife is a General Manager), where the empowerment of women in the new Egypt is awarded importance equivalent to the value of hard work to achieve progress.

The female protagonist, played by singer Shadia, works at one of the major economic projects built by Nasser, and supervises a mostly-male workforce, one of whom is none other than her husband, played by Salah Zulfikar.

Produced in a period of time when many women were empowered with the help of the regime to enter into many new professions, Shadia refuses to live according to the values of the ‘old’ eastern Harem system.

“Women in the East have gained their rights. We want to show you that we are suitable to occupy leading positions,” she ‘fights back’ against a reluctant ‘manly spouse’ in a famous scene in the 60s classic.

Other films supported Nasser’s goals and the revolution: both the 1958 Bab Al-Hadid (Cairo Station) by Youssef Chahine, and the 1962 Siraa Al-Abtal (Struggle of Heroes, 1962) showed the need for a vanguard in the revolutionary process: a militant worker in the first or a doctor who serves a poor community in the second.

In Sira Al-Abtal, the doctor protagonist is transferred to a poor village controlled by aristocrats, and is put in a situation ‘where the revolutionary should overcome the reactionary and liberate the farmers from ignorance, disease, and occupation.’

In his least-known socialist-realist masterpiece, the 1972 Al-Nas wal Nil (The People and the Nile), Chahine dramatised – or rather documented – the triumph of building Aswan’s High Dam.

The film, highly influenced by Soviet cinema and Egyptian drama of the time, was shot in 1969, but saw the light in 1972.

Despite its socialist-realist approach, the film’s debut was delayed due to ‘objections’ by both ‘socialist’ governments.

Basing the success of love stories on the completion of the grand nationalist project of the Nasser era, the film avoided shedding light on the individual characters and chose to depict them in a parallel to create a collective of incidents.

Between two wars: the rise and fall of Abdel-Nasser

For the regime, similarly to the construction of the High Dam, the 1956 nationalisation of the Suez Canal was considered a unique patriotic accomplishment.

Nasser’s decision to take back the canal from the British was met by the Tripartite Aggression, a war launched by England, France and Israel to defeat Egypt’s young independence.

Nasser, and Egypt, ultimately prevailed thanks to international pressure against the aggressors, popular support for Nasser at home as well as guerrilla resistance in the cities of the Canal.

The film titled Port Said was shown in cinemas weeks after the failure of the invasion.

The ending scene features a brigade of Egyptian guerrilla fighters surrounding a British camp, chanting the name of Nasser.

The film also used real footage of blowing up the statue of the symbol of Egypt’s submission to European colonialism pre-1952, Ferdinand de Lesseps, in Port Fouad city on the Canal.

Nasser came out of the war an anti-colonial pan-Arab hero.

In this context, in 1963 Chahine directed Al-Nasser Salah Al-Deen, a historical depiction more or less of Nasser accomplishments “set centuries earlier in the Crusades’ context.”

The character of Salah Al-Deen (played by Ahmed Mazhar) is a Muslim of Kurdish origins who united the Arabs to regain Jerusalem from the selfish, materialist, and corrupt European crusaders.

In the final analysis, anything but historically accurate, the film is a reflection of how the intellectual class and the masses thought of their leader.

Nevertheless, the biggest challenge to the depiction was the June 1967 Egyptian defeat at the hands of Israel, when both Egyptian soil and pride were stripped by Zionism.

In shock and awe moments after the regime’s acknowledgment of its defeat, people ran in the streets to affirm their support for Nasser, while Egyptian troops remained trapped by the Israelis in Sinai.

Filmmaker Ali Abdel-Khaleq captures this historical moment in the 1972 Ughnia ala al-Mamar (Song on the Passageway), as he dramatised the soldiers’ feelings on war and defeat.

The film narrates the story of how five under-equipped Egyptian soldiers abandoned by their battalion leaders refuse to retreat.

In his turn, Chahine argued in the 1972 Al-Asfour (The Sparrow) that the defeat came as result of the government’s corruption and oppression.

If June 1967 was a tough blow to the 23 July Revolution, January 1970 would have been the knock out.

The theorist and the face of the fifties and sixties died, adding insult to injury to a nation already traumatised by military defeat.

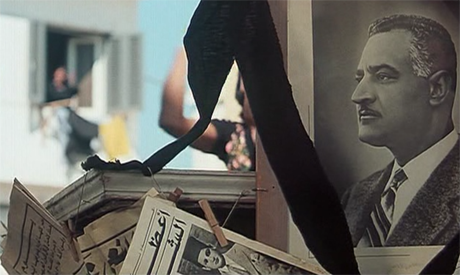

Egyptian directors Hassan Reda, Khalil Shawqi, Shadi Abdel-Salam, Ahmed Rashad, Mohamed Kinawi, Ali Abdel-Khaleq, and New Zealand cinematographer John Feeney joined to depict Abdel-Nasser’s phenomenal funeral in 1970.

Narrated by actor Mahmoud Yassin, the 30 minute documentary The Farewell Ballad (Unshodat Al-Wadaa) paints how Egypt collapsed into tears.

Footage of millions of people marching on the Qasr Al-Nil Bridge, accompanied by drums and chants, captured the agony: from fainting mourners, to women running in the streets carrying Nasser’s photo, to a young officer weeping and kissing the coffin.

A more conceptual depiction of the death of Nasser found its way into Chahine’s 1975 The Return of the Prodigal Son, where Ali, played by Ahmed Mehrez, acted out the now-cynical but once-energised sixties generation.

The peak of the plot marks both the death of the leader and the return of the prodigal son to his struggling community, an imagined messiah who also, like his people, believed that Nasser was “the teacher, the leader, and the big brother.”

Chahine used this twist to directly criticise the radical change in Sadat’s policies in the post-Nasser era of the early 1970s and the retreat from his ‘socialist principles.’

Wave of anti-Nasserism

The same year that saw the release of The Return of the Prodigal Son also witnessed the peak of anti-Nasser campaigns in Egyptian newspapers and intellectual circles.

The revisionist wave dealt a low blow to all that the July Revolution stood for – land reform, free education, nationalisation of mega projects – leaning on criticism of Nasser’s notoriously repressive security apparatus.

By the time this campaign started, most of Nasser’s men had been sent to prison on charges of high treason, with former president Sadat pushing the agenda for countering the old “power centres.”

Three productions, Al-Karnak (1975), the 1978 Wara Al-Shams (Beyond the Sun), and the 1979 Ihna Bitua’ Al-Autobis (We Were Just Riding a Bus), served the same purpose of condemning the practices of Nasser’s police, and intelligence apparatus against citizens.

The three films either start with the 1967 defeat or ends with it; their hypothesis is that the defeat was the either result of or the reason for the creation of a regime of torture and brutality, especially against political prisoners.

Nostalgia

Years after the end of the Nasserist era, the legacy of the 23 July Revolution remains prominent both in the nationalist narrative in government history books and in the hearts and minds of its supporters among and the lower middle classes who were changed by it.

The defence of Nasserism however always meant an onslaught on Sadatism.

In the 1991 Al-Mowaten Masry (The Egyptian Citizen) Salah Abu Seif depicts a story of the very farmers, who once prospered when Nasser distributed nationalised proportions of land to them, but were now faced with new laws that returns land back to feudal landlords.

In the film, actor Ezzat Al-Alayly who plays a poorer farmer, is threatened with the loss of land-reform gains. The old feudal landlord, played by Omar Sharif, is now the village’s mayor. The only way for Al-Alayly to keep his land is to send his son Masry to the military service to save the mayor from the ordeal.

In a memorable scene, Al-Alayly sits barefoot on his land, imagining himself as a lawyer defending the farmers.

“Your honour, in the old days the land was owned by a few… Abdel-Nasser left the rich Pashas enough. He also gave to the poor: two Feddans here, three Feddans there. The poor are those whose sweat is the reason the land is green,” we hear the grieving father say.

Nasserist themes continue to return in cinema, though less frequently and mostly intertwined with other topics.

As late as 2009, in Dokkan Shehata (Shehata’s corner store) director Khaled Youssef drew two scenes where Nasser is remembered for pride and healing.

The protagonist’s father asks the son to cover the crack on the wall with a portrait of Abdel-Nasser.

“The crack is too big to be covered,” replies the son.