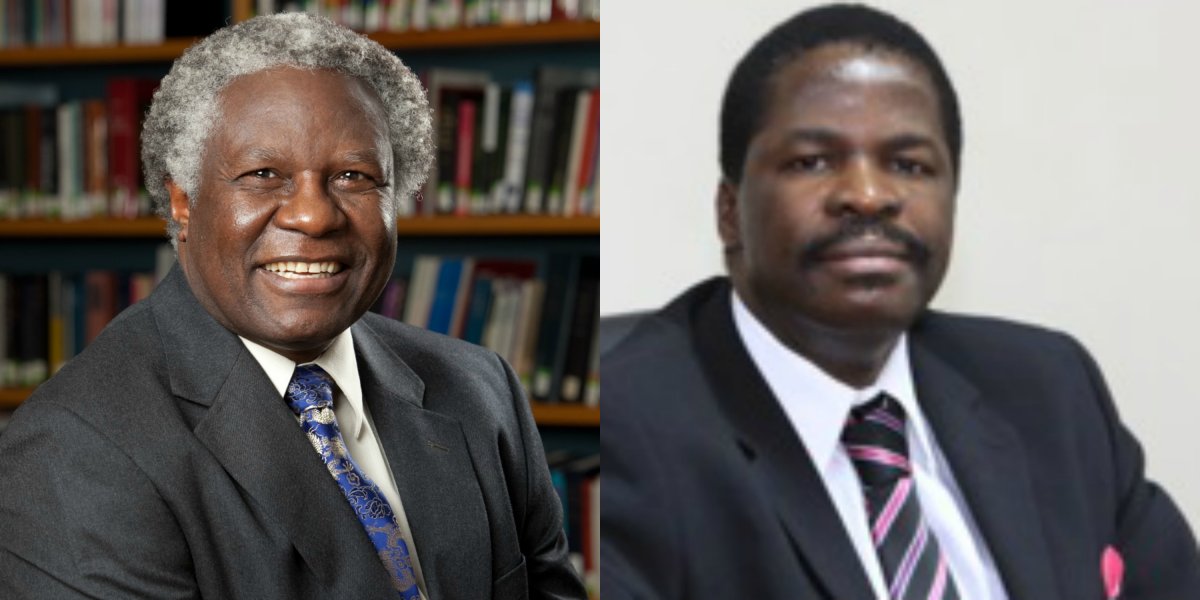

The following opinion piece was written by Calestous Juma, who is professor of the Practice of International Development at Harvard Kennedy School, and Francis Mangeni, who is director of Trade, Customs and Monetary Affairs at the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) in Lusaka, Zambia.

A major trade deal signed in June 2015 is about to remake Africa. Dubbed the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA), the 26-nation market created by this deal will liberalize intra-Africa trade, foster cross-border infrastructure investment, and stimulate industrial diversification.

The TFTA seeks to merge three existing regional organizations: the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the East African Community (EAC), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). The result is a territory twice as big as the United States with a population of 632 million and a combined GDP of $1.3 trillion.

African countries have traditionally been associated with the export of raw materials to industrialized countries. As a result, there is little free tradewithin Africa. But while many have long believed that intra-Africa trade is largely in unprocessed goods and raw materials, recent analysis has firmly established that more than half of intra-Africa trade is in intermediate and manufactured goods. Most of the imports, especially from developed countries and emerging powers, are in capital goods such as machinery for production.

Despite the rise in regional trade, only about 12 percent of the continent’s commerce is internal, compared with 70 percent in Western Europe, 50 percent in Asia, 40 percent in North America, and 22 percent in South America.

Because of the small size of domestic markets, there has previously been pressure to protect local industries from products imported from other African countries. This results in higher penalties for intra-African imports than for goods coming from outside the region. On average, products being sold within Africa attract a tariff of 8.7 percent, whereas similar goods coming from outside the region have a tariff of 2.5 percent.

There are also large imbalances in the application of tariffs between North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa. For example, Tunisian exports to Ethiopia attract a 15 percent tariff protection, while the opposite flow is given a tax of 50.4 percent. A Moroccan exporting to Nigeria pays almost four times as much as a Nigerian exporting to Morocco.

The planned tariff liberation of 60–85 percent will significantly facilitate cross-border flow of goods and services. It will also stimulate production and increase the internal tax revenue collected by member states. By maintaining economic growth of six to seven percent, Africa is projected to have a GDP of US$29 trillion by 2050, equivalent to the current combined GDP of the United States and the European Union. This will help spread prosperity and reduce poverty.

A larger African market will also stimulate investment in infrastructure. It is estimated that Africa needs to invest nearly US$100 billion in infrastructure per year over the next decade to meet its economic objectives. It is currently meeting less than half of that target. The TFTA will help create the predictability needed to attract local and international investors. Building infrastructure projects will also help create new jobs and foster the growth of engineering capabilities.

Probably the most important benefit of an integrated African market will be industrial development. Today, most African markets are too small to support large industrial investments, and the use of import duty to protect local industries undercuts the prospects of deepening trade.

The stage is now set for a new phase of industrial development. In fact, much of the intra-African trade that has been recorded over the last decade has come from growth in manufacturing. A liberalized continental market will help spur further industrial growth. This, combined with infrastructure investments and technology acquisition, will enable African firms to tap into global value chains, and will position Africa as a viable destination for new industrial investors.

The TFTA builds on achievements and lessons learned through existing trade blocs. It is not a new organization. In fact, it is a way to create the African Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA), whose negotiations were launched in South Africa in June 2015. Inspired by the diplomatic progress made under the TFTA deal, African presidents have committed themselves to create the African Economic Community by 2017.

The way ahead for Africa is long. Following tariff liberalization, the continent will start negotiating the free movement of services and people. Other areas that need to be negotiated include competition policy and intellectual property.

The TFTA is a major milestone in Africa’s economic development. It paves the way for the establishment of a single African free market area using harmonized trade policies and regulations, reducing the cost of doing business and streamlining future trade negotiations.

The expansion of regional trade through COMESA has attracted foreign firms such as First Quantum Minerals, British Petroleum, Qatar Petroleum, MTN Group, Bharti Airtel, Samsung Electronics, and Huawei Technologies to invest in the region. Local firms such as the UAP Group, Kenya Commercial Bank, Nakumatt, and Zambeef are also increasing their cross-border trade.

Above all, the TFTA will stimulate economic growth and help spread prosperity through infrastructure investments and industrial development. It will prepare Africa to become a more serious player in the global economy.

BIO: Calestous Juma (Twitter @calestous) is professor of the Practice of International Development at Harvard Kennedy School. Francis Mangeni (Twitter @francismangeni) is director of Trade, Customs and Monetary Affairs at the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) in Lusaka, Zambia. This article draws from their forthcoming book, Trading Up: Africa’s Regional Economic Integration.