With less than a year to go, how are preparations going? Who is running? What will be the key issues?

It is now less than a year before Nigeria’s critical general elections. In those polls, currently scheduled for 16 February and 2 March 2019, tens of millions of citizens will vote in what could be some of the country’s most fiercely fought contests yet.

It is now less than a year before Nigeria’s critical general elections. In those polls, currently scheduled for 16 February and 2 March 2019, tens of millions of citizens will vote in what could be some of the country’s most fiercely fought contests yet.

How are preparations going? Who is running? What will be the key issues?

Preparations for the elections

Since Mahmood Yakubu took over as chair of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) in 2015, the body has carried out over 167 elections. One was nullified in court. INEC has also undertaken several institutional reforms. This includes launching a new strategic plan, working on a youth engagement strategy, and reviewing its gender policy. It has promoted deserving staff and, in an unprecedented move, prosecuted officials found to have committed wrongdoing in the 2015 elections.

Ahead of 2019, the commission has set up a committee to review the voting process and transmission of tallies. For the first time since the return to democracy in 1999, INEC is also conducting continuous voter registration.

Despite these giant strides, however, the body is facing some challenges.

Because of delays caused by a dispute between the president and Senate, for example, INEC still only has 30 out of 37 Resident Electoral Commissioners, the key officials responsible for organising elections at the state level. Continuous voter registration, which opened in 2016, has also experienced glitches, with some citizens complaining of being unable to register. This led INEC to recently deploy additional registration machines and increase the number of registration centres to 1,446 nationwide. Meanwhile, the cost of running the elections may also present a challenge. This is especially the case given that Nigeria has just exited a recession.

The commission has also been given additional headaches following last month’s local elections in Kano State. In the aftermath of that poll, a video emerged showing young children thumb-printing ballot papers. INEC did not oversee that election, but some claimed it had been responsible for registering the underage voters in the first place.

In response to this criticism, the commission set up a panel to probe the alleged underage voting and examine the nearly 5 million voters on the register in Kano. INEC has previously helped other countries in West Africa clean up their electoral registers, most recently ahead of Liberia’s run-off polls in December 2017.

Who is running?

In the 2015 elections, Nigeria had 40 registered political parties. Ahead of 2019, there are now 68, with 33 more being considered for registration.

The ones to beat this time around will be the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC). This party was created ahead of 2015 through a merger of what were then the country’s four biggest opposition parties. Its growing ranks were further boosted when several figures from the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), in power at the time, crossed the floor.

In the election, the APC enjoyed an historic victory and ended the PDP’s political dominance, which had lasted since 1999. But since those heights, internal rivalries have come to the fore and prevented it from emerging as a cohesive force. The APC continues to run as an amalgam of the interests that created it in the first instance, with intra-party disputes emerging at both federal and state levels.

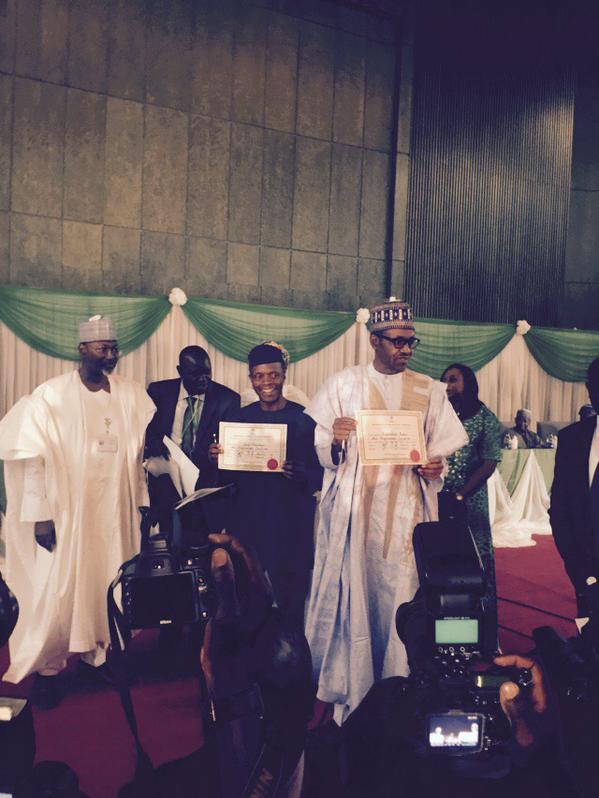

The incumbent President Buhari is the front runner to be the party’s flagbearer in 2019. However, aside from his mixed record in office, his advanced age of 75 and ill health could arise as an issue. Many are asking whether he will be fit to govern if re-elected, especially given that he spent several months of his first term receiving treatment in London for an undisclosed ailment.

The main opposition PDP has faced similar infighting to the APC since 2015. After the election, the party faced a bitter legal battle over the leadership of the party with Ahmed Makarfi eventually confirmed as the party chair. Since then, the PDP has held a national convention in which new officials were elected. Some regions were marginalised, however, and the party has yet to calm concerns about the state of its internal democracy or shed its reputation for corruption, which it developed over its 16 years in office.

Several candidates are lining up to bid to be the PDP’s presidential nominee. They include former Vice President Atiku Abubakar, who recently crossed over from the APC. Often described as a serial defector, Atiku has commenced consultations and is regularly voicing his opinions on policy matters. At 71, his age and unproven corruption allegations remains the albatross around his neck. Other aspirants from the PDP include controversial governor of Ekiti State, Ayodele Fayose, and former governors of Kaduna and Jigawa, Ahmed Makarfi and Sule Lamido respectively.

Along with these two big parties, Nigeria could, for the first time, also see a powerful third party emerge in 2019. The most popular phrase in the country today is “Third Force” and various groupings are attempting to harness the appetite for an alternative to the APC and PDP.

30 opposition parties have joined forces under the banner of the Coalition for a New Nigeria (CNN). Former president Olusegun Obasanjo has helped set up the Coalition for Nigeria Movement (CNM). And groups such as the Nigerian Intervention Movement, Revive Nigeria and Emerging Leaders’ Summit are also trying to jostle for position. Regarding the presidency, the likes of motivational speaker Fela Durotoye, former deputy governor of Central Bank of Nigeria Kingsley Moghalu, and founder of the online whistleblowing site Sahara Reporter Omoyele Sowore have all expressed their intention to challenge the main parties’ candidates.

At the same time, citizen-led groups are also making their voices heard. The Red Card Movement, led by former minister and #BringBackOurGirls campaigner Oby Ezekwesili, is calling for the APC and PDP to be “sent off”. Meanwhile, the Not Too Young To Run movement is demanding the inclusion of young people in the political space.

Unfortunately, there is less momentum behind efforts seeking to enhance the participation of women in politics. Less than 6% of Nigeria’s lawmakers are female, one of the lowest proportion in Africa, and while more marginal parties may make space for women and youth to lure voters, the same is likely to be less true of the big parties.

The issues that will determine the 2019 Nigeria elections

Insecurity

One of the biggest issues that will determine the 2019 general elections is insecurity, which is affecting communities across the country. Ongoing instability could affect the vote itself and will certainly be a big issue on the campaign trail.

On Boko Haram in the North East, the APC will claim to have successfully tackled the insurgency. The PDP and other opposition parties will argue against this and likely emphasise the dire humanitarian situation. The candidates may try to woo internally-displaced persons as the election nears.

Another matter will be the conflict between herders and farmers, which has arguably become Nigeria’s most pressing internal security threat. As hundreds have died in clashes over land disputes in a dozen states, the Buhari administration has been criticised for its poor handling of the issue. The conflict – and lack of accountability for heinous crimes – predates the APC’s rule, but its severity and death toll have escalated in recent years.

In the South East, Biafra separatists continue to call for independence. The most prominent voice in this is the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), whose leader Nnamdi Kanu has been missing for several months. The group has vowed that no election will take place in the south east until a referendum on secession is called.

Finally, gang violence has resulted in several deaths recently, particularly in the Niger Delta and South-South region. Worrying, these groups are often instrumentalised by politicians around elections.

The economy

The economy will be another crucial issue. Nigeria is still suffering from a fuel scarcity, while the economic downturn continues. When Buhari came into office, the price of dollar was around N170. Today that figure is closer to N360.

Nigeria exited its first recession in 25 years in the second quarter of 2017, but growth remains sluggish. The country continues to depend on oil, while un- and under-employment have increased notwithstanding the administration’s novel social intervention programmes (SIP).

Corruption

Buhari rode to victory in 2015 as the anti-corruption candidate, vowing to launch a war on graft. Corruption will once again be an important issue, but the incumbent will struggle to present himself as the same clean crusader this time around.

While Buhari has embarked on some anti-corruption measures, critics note that his allies have avoided prosecution. Various of his associates have been fingered in scams, such as his chief-of-staff Abba Kyari, while the president has been perceived to have targeted his opponents.

The uncoordinated approach taken by agencies in the fight against corruption have contributed to the fact that Nigeria has actually dropped 12 places from 136 to 148 in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.

Social media, fake new, misinformation and disinformation

As in politics and elections across the world, social media is set to play a major role in Nigeria’s 2019 campaign.

In the 2015 elections, hate speeches and misinformation spread far and wide, with Buhari targeted in particular. After the elections, incredible rumours and lies continued to abound, to the extent that there were even allegations that the man that eventually returned from London after prolonged illness was not in fact the real Buhari, but a cloned version from Sudan.

Ahead of the recently concluded Anambra governorship elections, we saw another example of how fast-spreading misinformation could almost skew a process. Rumours emerged on social media that soldiers had invaded schools in Ozobulu, Anambra State, and were forcefully injecting pupils with poisonous substances that cause monkey pox. This led to the shutdown of schools in Imo, Enugu, Abia, Anambra and Ebonyi state and even affected Rivers and Balyesa states. The false story was said to have been posted on the Facebook page of the IPOB, which had vowed to disrupt any elections in the region.

Nigeria’s social media space is generally highly susceptible from manipulation by influential individuals with vested interests and little sense of electoral ethics. They are ready to confuse or divide people along ethnic, religious or other lines to serve their own ends. In 2015, the PDP recruited Cambridge Analytica. In 2019, those with sufficient resources may again solicit the services of international PR firms with records of employing questionable methods.

With that declaration, the race to lead Africa’s largest democracy is underway.

The path ahead could be tough for his All Progressives Congress (APC), the opposition People’s Democratic Party (PDP) and any other party that may contest the vote.

The region includes several states that are likely to be hotly contested, including Plateau, Taraba, Nasarawa and the Federal Capital Territory, which the PDP won by margins ranging from three percent to 12 percent in 2015.

Can Buhari win again?

Buhari’s 2015 victory was built on three promises: to rid Nigeria of its endemic corruption, to fix the economy and to defeat threats to security.

The results have been mixed. He has not brought an end to the war with the Boko Haram Islamist insurgency, now in its tenth year. The economy entered and climbed out of recession under Buhari, yet the average Nigerian is still getting poorer; and opponents say his administration is failing to tackle endemic corruption, targeting only the president’s enemies and ignoring allegations against his allies.

After spending five months in Britain last year being treated for an undisclosed ailment, opposition groups and other critics said he was unfit for office and his administration was beset by inertia.

If Buhari wins again, his opponents say, Nigeria would be in for another four years of political torpor.

On the other hand, the president’s supporters say the opposition has little to offer beyond “Not Buhari”, a sign of Nigeria’s personality-driven politics.

Divisions and alliances

Nigeria is deeply divided. One of the most fundamental rifts is between the mainly Muslim north and the largely Christian south, and the population is fairly evenly split between the religions.

Africa’s most populous country also has more than 200 ethnic groups, with the three largest the Hausa in the north, the Yoruba in the southwest and the Igbo in the south-east.

That has led to an unofficial power-sharing agreement among Nigeria’s political elite.

The presidency, in theory, is to alternate between the north and south after every two four-year terms. Buhari, a northern Muslim, has held the post since 2015. His predecessor, the PDP’s Goodluck Jonathan, is a southern Christian. In keeping with the accord, the PDP is set to select a northerner as its candidate for 2019.

Those divisions play into what could be one of the major issues of the 2019 elections: deadly violence between mostly Christian farmers and mainly Muslim nomadic herders that has broken out in the Nigerian hinterland states known as the Middle Belt.

Buhari’s critics say he is soft-peddling justice for the killings because he, like most of the herders, is from the Fulani ethnic group and is Muslim.

The presidency denies that criticism, which also largely ignores the fact that there have been deaths in both communities as a cycle of reprisal attacks shows little sign of ending.

Swing states

This could turn the Middle Belt, much of which voted for Buhari in 2015, into some of the most crucial swing states next year.

Buhari won in 2015, becoming the first candidate to defeat an incumbent president, in part because he gained votes in the Middle Belt, where the predominantly Muslim north and Christian south collide.

“The region includes several states that are likely to be hotly contested, including Plateau, Taraba, Nasarawa and the Federal Capital Territory, which the PDP won by margins ranging from three percent to 12 percent in 2015,” said Ben Payton, head of Africa research at Verisk Maplecroft.

The youth factor

With a booming young population, Nigeria’s median age is just 18, according to the United Nations. Many youth see Nigeria’s ageing leaders as out of touch. Buhari, 75, is the oldest person to helm Nigeria since the transition to civilian government in 1999. That has sparked “Not Too Young to Run” campaigns to allow younger people to seek office.

Nigeria’s former military leaders retain a strong influence over politics nearly two decades after the advent of civilian rule. Buhari himself is a retired general who was head of state from 1983-1985.

Other military-era chiefs continue to wield political leverage, including the likes of Olusegun Obasanjo, who led the country in the 1970s and was president from 1999-2007, and Ibrahim Babangida, who ruled from 1985-1993.

The parties

The two main parties, the ruling APC and opposition PDP, do not have clear ideological differences. Competition for control of national oil revenues by elites, patronage and complex rivalries between Nigeria’s hundreds of ethnic groups have played a much bigger role in elections than ideology.

No clear candidate for the PDP has emerged. Some members see Atiku Abubakar, who has signalled he may run, as the best choice. A local tycoon and former vice president for the PDP under Obasanjo, he has made numerous unsuccessful bids to become Nigeria’s leader. Abubakar became a key ally and funder of Buhari during the 2015 campaign, only to once again switch sides late last year and indicate his desire to contest again.

It is also possible that a third major party may form, with rumours swirling of potential powerful backers including Obasanjo and Babangida.

Social media use during elections

Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal has hit Nigeria. The government has launched an investigation into allegations that the firm was hired to interfere with Buhari’s campaigns in 2011 and 2015, on behalf of the PDPand then-president Goodluck Jonathan. Jonathan, through a spokesman, denied any knowledge of the alleged interference. Cambridge Analytica has not commented on the allegations.

Road to 2019

Voter turnout in the 2015 election was 29.4 million, or 44 percent of registered voters, according to Independent National Electoral Commission data.

Party primaries run from Aug. 18 to Oct. 7. Campaigning will be held from Nov. 18, 2018 to Feb. 14, 2019, and the presidential elections are set for Feb. 16, 2019.

The candidate with the most votes is declared winner as long as they have at least one-quarter of the vote in two-thirds of Nigeria’s 36 states and the capital. Otherwise there is a run-off.