Amid all the distress of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, progress on the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) has been a bright light.

The Secretariat was established in Ghana, and Africa’s most populous economy, Nigeria, joined 33 other countries in ratifying the agreement. This progress is important. The AfCFTA has been a long time coming. 2020 marks two decades since a major decision among African governments to strengthen the coordination of the continent’s economic policy. The turn of the millennium saw, in Lomé, Togo, the Constitutive Act of the African Union agreed – setting the stage for the AfCFTA 20 years later.

But much more was envisioned in Lomé, and as 2020 also brings new concerns about African financial stability in the wake of Covid-19, the time is now to turn from trade to money, money, money.

The triple emphasis is appropriate, because the idea governments committed to all the way back in 2000 was to create a set of three, exclusively African financial organisations: an African Central Bank (ACB); an African Monetary Fund (AMF), and an African Investment Bank (AIB).

The vision was similar to what we see in Europe today – a single currency; a European Central Bank (ECB) that can bail out European economies on their terms; and a separate, exclusively European Investment Bank (EIB) that can fund infrastructure and leverage private investment into long-term projects in the region. There are similar analogies for American states and Chinese provinces.

The rationale for the three African financial institutions is as clear as the rationale for the AfCFTA. Right now, Africa’s dependence on the rest of the world for finance is a major impediment to development. Debt-to-GDP ratios on the continent can rise not because of actual increases in borrowing for road, rail or even digital infrastructure projects, but simply because risk perceptions of Africa worsen.

Having emerged highly damaged from the external-interest-rate-hike-induced debt crisis in the 1990s and accompanying structural adjustment policies required by the IMF and World Bank for bailouts, this need for financial independence was starkly obvious to African leaders 20 years ago.

Indeed, post-2000, some progress was made. The key documents for the AIB were drawn up back in 2006. So far, 22 African countries have signed up, and six formally ratified – Togo, Libya, Congo, Chad, Burkina Faso and Benin. Similarly, the documents for the AMF were drawn up, and a location for headquarters identified – Yaoundé, Cameroon.

The documents were adopted in 2014, and so far, 12 African countries have signed on the dotted line. One of them – Chad – has even made a capital deposit. Only the ACB is still pending, with an expected timeframe for the establishment around 2028~2034.

Lenders shun Africa

But if 2020 is to have any impact on African integration in 2021, it has to be to a reminder that this external financial dependency is unsustainable.

The majority of African leaders and citizens have done everything they can to fight against Covid-19, in sharp contrast to many other countries around the world.

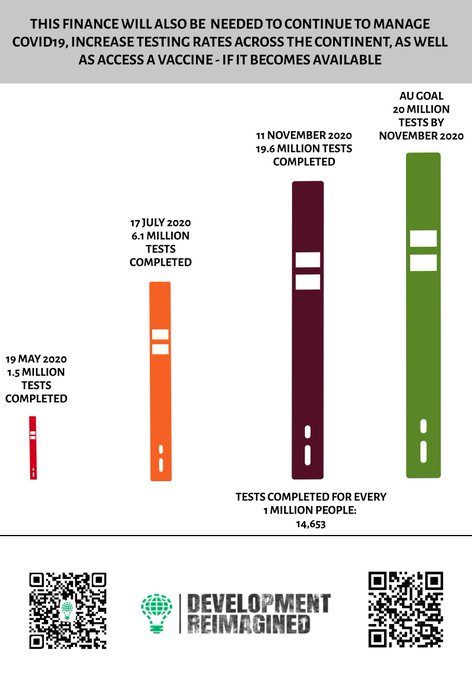

Analysts at our firm, Development Reimagined, found that 37 African countries implemented some degree of social distancing measures before recording 10 cases. Ten of these countries implemented the measures before seeing any cases at all. African governments together have put aside at least $68bn collectively to deal with Covid-19, through measures that we estimate reach 175m people.

By the end of May, 37 African governments had announced special financing support for SMEs. Five – Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Uganda and Mozambique – had special schemes to encourage local firms to repurpose to manufacture PPEs and other health equipment.

Covid-19 demonstrates Africa is not an incompetent, high-risk continent. Governments are active and involved, and citizens respond. Indeed, research from the Political Economic Research Institute (PERI) and Global Financial Integrity (GFI) have proven that Africa is a net creditor to the global economy.

But the reality is that this understanding does not – as yet – translate into money. The perception of risk persists. Pleas from African governments to external lenders to take some responsibility to help create fiscal space to address Covid-19 have gone mostly unanswered.

Where they are answered – for example through the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) – they are limited to the poorest countries, and come loaded with new conditions, potentially taking governments back to the 1990s.

In November this year, bondholders determined that Zambia was “defaulting”, after the government asked for “breathing space” in the form of a six-month payment suspension valued at under $50m, meaning Zambia’s access to finance for potential growth-inducing projects will be curtailed.

The government had prior to this announced direct Covid-19 expenses of over $100m. Figuratively speaking, if a country asks for breathing space, it can be deduced that such a country feels it is suffocating. Economic development or recovery cannot happen under such conditions.

Levelling the playing field

So what can African governments and stakeholders do in these circumstances? Others have advocated for the – unconditional – release of special drawing rights, held by the IMF, as was done in the 2008 financial crisis for wealthy nations. We have argued in African Business magazine and elsewhere for new, innovative and longer-term solutions such as a “borrowers’ club”.

But the work on Africa’s own, exclusively African financial organisations is also a crucial, long-term answer that can be combined with others. Yes, the African Development Bank (AfDB) exists, and is an incredibly important institution for Africa. But as we saw play out in mid-2020 with external questioning of the Bank’s president, Akinwumi Adesina, the fact that the AfDB board and capital is inclusive of non-African countries, suggests its financial decisions and attitude to risk are heavily externally influenced as well.

The fact is, European, American, Chinese and other populations benefit hugely from integration and independence of their own financial systems. These systems allow for elimination of foreign exchange issues that disrupt trade; they enable exchange rate stability to avoid competitive depreciation; and they also enable new debt to be issued promptly to shield citizens and businesses from challenges such as Covid-19 – without prior, protracted consultation, negotiation and concessions with the rest of the world. African citizens – and others around the world – deserve these benefits too. The playing field needs levelling.

The whole point behind the creation of the African Union and the plan for its new trade, financial and other institutions 20 years ago was this levelling. A unified position was required to effectively deal with dire economic conditions that plague the African continent.

The fact that the AfCFTA has swung into action in the year of a pandemic provides ample inspiration for a further, proactive 2021 agenda. The work has already been done on the documents for these key financial bodies. It’s time for African governments to get signing again. 2021 needs to be all about the money.

Hannah Ryder is the CEO of Development Reimagined, a pioneering African-led international development consultancy based in China.

Ovigwe Eguegu is a policy adviser at Development Reimagined and a specialist in geopolitics.