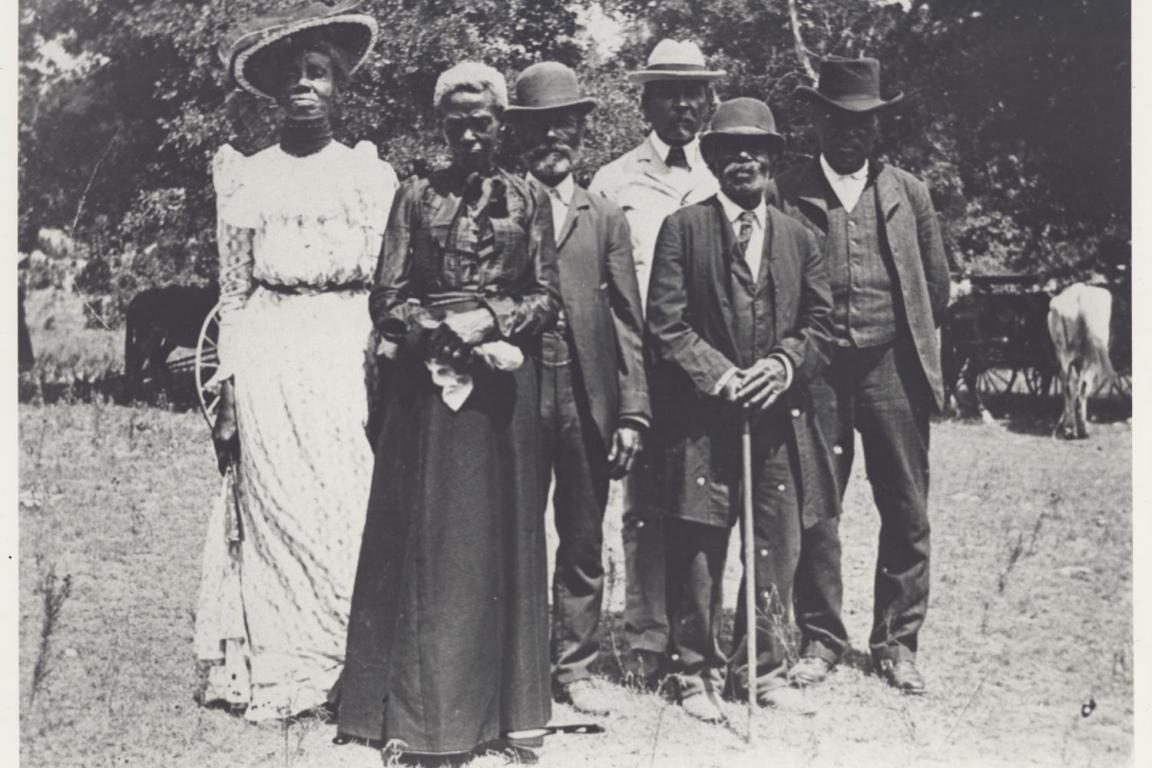

On June 19, 1865, nearly two years after President Abraham Lincoln emancipated enslaved Africans in America, Union troops arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas with news of freedom. More than 250,000 African Americans embraced freedom by executive decree in what became known as Juneteenth or Freedom Day. With the principles of self-determination, citizenship, and democracy magnifying their hopes and dreams, those Texans held fast to the promise of true liberty for all.

The Historical Legacy of Juneteenth

On “Freedom’s Eve,” or the eve of January 1, 1863, the first Watch Night services took place. On that night, enslaved and free African Americans gathered in churches and private homes all across the country awaiting news that the Emancipation Proclamation had taken effect. At the stroke of midnight, prayers were answered as all enslaved people in Confederate States were declared legally free. Union soldiers, many of whom were black, marched onto plantations and across cities in the south reading small copies of the Emancipation Proclamation spreading the news of freedom in Confederate States. Only through the Thirteenth Amendment did emancipation end slavery throughout the United States.

But not everyone in Confederate territory would immediately be free. Even though the Emancipation Proclamation was made effective in 1863, it could not be implemented in places still under Confederate control. As a result, in the westernmost Confederate state of Texas, enslaved people would not be free until much later. Freedom finally came on June 19, 1865, when some 2,000 Union troops arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas. The army announced that the more than 250,000 enslaved black people in the state, were free by executive decree. This day came to be known as “Juneteenth,” by the newly freed people in Texas.

The post-emancipation period known as Reconstruction (1865-1877) marked an era of great hope, uncertainty, and struggle for the nation as a whole. Formerly enslaved people immediately sought to reunify families, establish schools, run for political office, push radical legislation and even sue slaveholders for compensation. Given the 200+ years of enslavement, such changes were nothing short of amazing. Not even a generation out of slavery, African Americans were inspired and empowered to transform their lives and their country.

Juneteenth marks our country’s second independence day. Although it has long celebrated in the African American community, this monumental event remains largely unknown to most Americans.

The historical legacy of Juneteenth shows the value of never giving up hope in uncertain times. The National Museum of African American History and Culture is a community space where this spirit of hope lives on. A place where historical events like Juneteenth are shared and new stories with equal urgency are told.

Why is Juneteenth Important?

Frederick Douglass once famously asked, “What to a slave is the Fourth of July?” To honor the anniversary of the freedom granted to those enslaved African Americans, we’ve pondered a similar question, “What is the significance of Juneteenth to the Black community?” In this three-part series we interviewed three experts at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) to find the answer: Mary Elliot, Curator of American slavery, and emancipation; Angela Tate, Museum Curator of African American women’s history; and Kelly E. Navies, Museum Specialist of Oral history.

In our previous post, NMAAHC staff explored the identities of the people who celebrate the holiday as well as the cultural and historical significance they place upon the date. In this, the third and final part of our discussion, we asked each curator to answer the question: Why is Juneteenth Important?

Mary Elliott, Curator of American Slavery

Juneteenth is important, because it reminds us of what we came through and what we can achieve.

As my colleagues mentioned, the reason General Order Number 3 existed and the Union Army fought to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation, is because slavery existed. It’s important to remember what we went through and that we were able to get out of the bondage of slavery as a nation. It’s an important reminder and it’s important that we understand what it took. It’s also important that the Juneteenth holiday survives. It allows each generation to reflect what more there is to do. Juneteenth places Black people at the center of the conversation about freedom, it’s meaning and manifestation in this nation.

July 4th is about liberty, but it was an imperfect liberty, because slavery still legally existed in the nation. I personally recognize both holidays because these are important moments in our shared history.

We should regularly consider the evolution of the meaning of freedom as we look at certain moments in the nation’s past and present. Someone can deeply appreciate why Juneteenth was important for the Poor People’s Campaign. Why Juneteenth is important in relation to the events that happened this past summer with the death of George Floyd. Why Juneteenth is important when we think about enforcing our rights to vote and how we define citizenship in this nation.

Juneteenth should really be a rallying call for all of us to think about the meaning of freedom, particularly regarding African Americans, as well as to the nation and the rest of the world.

Angela Tate, Curator of African American Women’s History

Juneteenth doesn’t feel fixed like July 4th. July 4th feels fixed in 1776, whereas Juneteenth always feels fluid and always willing to be adaptable to the incoming and upcoming generations. It always feels relevant to this continuous quest and fight for freedom and equality.

I’ve seen a lot of tweets over the past year from African Americans, African immigrants to the United States, West Indians and how they tie Juneteenth to their own country’s celebrations. I remember seeing a tweet from a Nigerian asking others from Nigeria to wish them a happy Juneteenth. They said, “I’m going to block you if you say happy 4th of July.” I remember another tweet from 2015 where someone said, “I celebrate Juneteenth and Nigerian independence as my independence days.” They don’t even celebrate the 4th of July. It’s not relevant to them.

This is not just a holiday that is fixed and has one meaning. It has a multiplicity of meanings to people of African descent in the United States. They also see it as relevant to Africa, the Caribbean, and any other place where there’s an African diasporic community. It’s a continuous struggle, a continuous fight, a continuous place of remembrance.

Juneteenth is also a site for political knowledge. It’s a time to recognize that you need to be registered to vote. You need to know what’s going on in your own city. You need to take control of your civic duty.

Again, Juneteenth, is not this fixed holiday as the 4th of July is. It’s not a neutral holiday where you just show up. Juneteenth requires you to be present, in the moment, and very specific about why you are showing up to celebrate it. It’s important for everyone to remember where it came from, but also how it has developed in other parts of the African diaspora within and outside of the United States.

So much has been said by my sisters preceding me, but what I think about when I reflect on that question is the 1619 project. There has been so much resistance to the 1619 project, which was an attempt to bring an understanding of slavery, and the history of slavery to the nation and the classrooms of America. But in places like Texas, where Juneteenth was born, you see the strongest resistance to this progressive curriculum.

As the daughter of a teacher and as a former teacher myself, I know that many of our students throughout the country are not learning this history. They don’t learn about Juneteenth in their classrooms. There are pockets, like Berkeley and Washington DC, where they’ve implemented a black history curriculum in the high schools, but there’s resistance throughout the country. Juneteenth facilitates the transmission of our history and our culture. If you are a child that isn’t in one of those towns and you aren’t learning this in your classroom, you can learn about Juneteenth in your city’s parade, or in your friend’s home.

When my family held Juneteenth celebrations in Oakland Bay Area, we would open our home to everyone in the community. We would have people spilling out of our parking lot and into our backyard. We would play our African drums and the police would show up when we got complaints about the noise. The police would come every year. I mean, seriously, this was a big deal! My dad didn’t care, because he owned that house outright, and he knew that we had the right to celebrate our freedom. However, not everyone has access to the space needed to exercise this right.

Juneteenth is here so that we can teach people who don’t always have access to this knowledge in their homes or in their schools. It gives us a space, not only physical, not only external, but a space in our hearts and in our minds.