The Turks used their presence to pressure the Emiratis there, then to incite the Somalis to turn against them after years of Emirati support for the nascent security forces in Somalia.Because he overreached his country’ abilities, Erdogan found himself compelled to shelve the Suakin base project and was content with a more modest relationship than the initial alliance he initially envisaged with the Somali government.

The Turks and the Somalis discovered that opportunism does not make for a long-term policy. As soon as tensions between Doha and its neighbours subsided, opportunist Turks and Somalis began to wonder if their relationship served any purpose whatsoever.

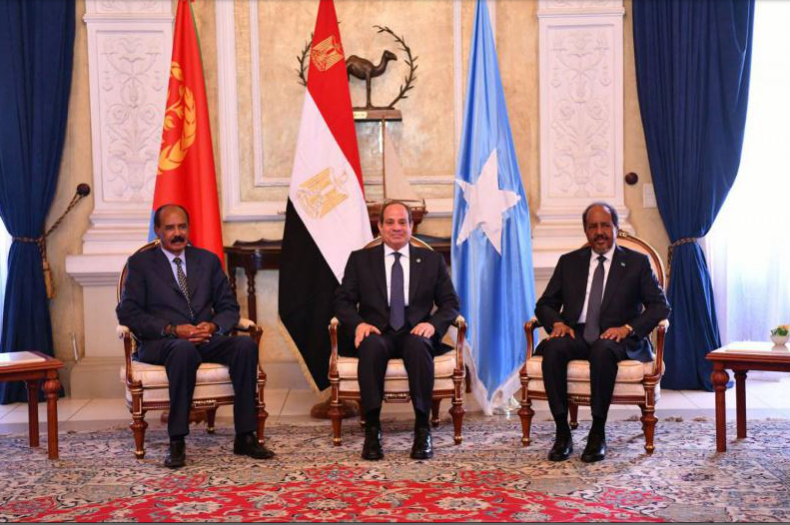

For some reason, the Egyptians have decided to re-enact the Turkish scenario. Instead of seeking a Suakin base in Sudan, they have headed for Eritrea, using the same lexicon from the relationship between Turkey and Somalia. They have sought to substitute themselves for Turkey by stationing Egyptian forces or advisors on the ground and delivering arms to support the Somali forces in the hope of entrenching Egyptian influence or gaining the initiative in the face of the Ethiopians. Cairo somehow believes it can succeed in the Horn of Africa where Turkey failed.

Most certainly, the Eritreans are different from the Sudanese. Many accusations can be levelled at Sudanese military leaders. Their role is one of the reasons for Sudan’s catastrophe. But all Sudanese leaders, since the time when their country was under the Egyptian crown, have never started any initiative without taking into account Egypt’s situation and its stature.

Even Islamists who infiltrated the Sudanese army have acted as if Egypt was part of the spoils they stood to reap, if and when they acceded to power. These are the same Islamists who brought new types of disasters upon their country, leading it to be divided and mired in all kinds of wars.

The Eritreans are different kinds of politicians, especially when it comes to their eternal leader Isaias Afwerki. This former revolutionary sees himself and his country as the centre of the universe. To this day, he has not dealt with anyone nor any country, since the days of the war of independence from Ethiopia, except within the logic of betraying his friends and backers.

There is no country in the region that did not support the Eritrean liberation movement in the seventies and eighties. But all these countries were rewarded with ingratitude. Afwerki is the embodiment of opportunism and betrayal. Perhaps this is what made everyone, except the Israelis, deal with him with the utmost caution. There is no reason to believe that Afwerki’s political logic has changed while he makes his overtures to Egypt and pursues what looks like an attempt to form an alliance with Cairo in order to antagonise the Ethiopians.

One ought to welcome Egypt’s decision to undertake a reassessment of its strategic position in the region and of the repercussions it faces from developments in the southern Red Sea, Bab al-Mandab Strait, the Gulf of Aden and the Horn of Africa.

The Egyptians have long denied the serious nature of the situation because they were driven by an historical syndrome stemming from their costly intervention in Yemen in the sixties and their interpretation of that intervention as one of the key reasons for their 1967 defeat by Israel.