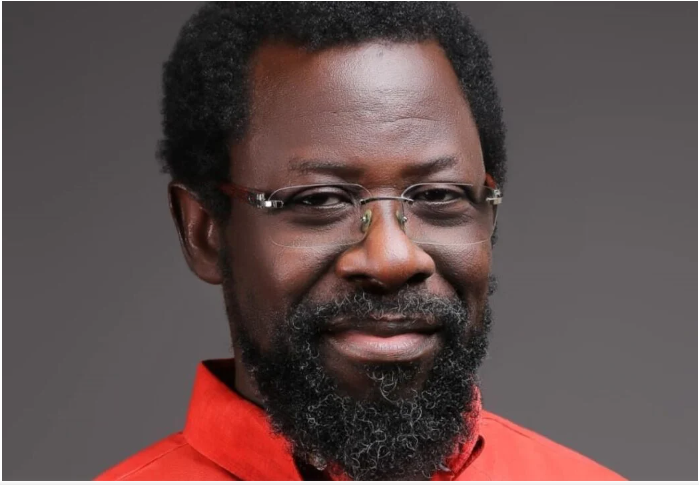

The arrest and continued detention of Dele Farotimi raise serious legal and ethical questions about due process, constitutional rights, and the rule of law in Nigeria. While his outspoken views and allegations against Chief Afe Babalola may be polarizing, this case transcends personal grievances and enters the realm of legal principles, procedural fairness, and the administration of justice. Before delving into the accusations of defamation, judicial corruption, or any underlying motives, it is essential to critically assess the legality of Farotimi’s arrest and the procedural steps taken by law enforcement.

The arrest and continued detention of Dele Farotimi raise serious legal and ethical questions about due process, constitutional rights, and the rule of law in Nigeria. While his outspoken views and allegations against Chief Afe Babalola may be polarizing, this case transcends personal grievances and enters the realm of legal principles, procedural fairness, and the administration of justice. Before delving into the accusations of defamation, judicial corruption, or any underlying motives, it is essential to critically assess the legality of Farotimi’s arrest and the procedural steps taken by law enforcement.

The foundational principle of modern jurisprudence is that no one should be subjected to arbitrary arrest or detention. Section 35 of the Nigerian Constitution guarantees the right to personal liberty, stipulating that no person shall be deprived of their freedom except in circumstances allowed by law and only with strict adherence to legal process. The issue at hand is not just the allegations leveled by Farotimi but whether the police followed due process in effecting his arrest and subsequent detention. This question is fundamental because the legitimacy of any trial or hearing stemming from such an arrest depends on the legality of the initial action taken by law enforcement.

Reports suggest that the police acted based on an investigation activity from Ekiti State, where Chief Afe Babalola resides. If law enforcement from Ekiti State obtained a valid arrest warrant and followed the legally required inter-state arrest procedure—such as notifying the Lagos State Police Command and involving its officers—then the arrest might be legally defensible. However, if these procedures were not meticulously observed, the arrest would be unlawful, regardless of the underlying accusations. Jurisdictional overreach has been a recurring issue in Nigeria’s law enforcement practices, often serving as a means to intimidate rather than to pursue genuine justice.

Furthermore, the circumstances of Farotimi’s arrest appear to reflect extra-legal force, drawing comparisons to practices reminiscent of authoritarian regimes. Historically, Nigeria’s democracy has grappled with accusations of judicial and executive overreach, where arrests have been carried out in a manner that undermines public trust in the legal system. The memory of the military junta era when political dissidents were routinely harassed under the guise of maintaining order cannot be ignored. The arrest of an outspoken critic like Farotimi evokes similar concerns about suppressing free speech through legal coercion.

It is also necessary to analyze the charge itself defamation. Although criminal defamation remains an offense in Nigeria (except in Lagos State), its application must be guided by proof of malicious intent, clear damage, and false statements made with the knowledge of their falsity or reckless disregard for the truth. Farotimi’s allegations against Afe Babalola, no matter how serious, must be proven to be false and maliciously intended to warrant a criminal conviction. His legal misstep, if any, lies in naming a specific individual and making direct accusations without, as of now, presenting indisputable evidence to back those claims. If he is unable to substantiate his claims in court, he risks legal consequences.

However, naming a person in the context of exposing perceived corruption is not inherently defamatory unless proven false. Truth remains a complete defense under Nigerian defamation law. If Farotimi can produce credible evidence that supports his assertions such as proof of judicial misconduct or documented instances of case manipulation the defamation charge may collapse. The court will need to assess the balance between freedom of expression and the protection of individual reputations, especially where issues of public interest are concerned.

Moreover, Chief Afe Babalola’s stature as a legal luminary complicates the narrative. His distinguished career, age, and public service have earned him immense respect. Yet, in legal terms, even a person of such prominence is not above criticism or legal scrutiny. If Babalola is truly aggrieved by defamatory statements, pursuing legal redress through a civil suit would appear more appropriate than invoking criminal defamation laws, especially in a jurisdiction like Ekiti State, where his influence is significant. This raises the specter of perceived judicial bias a critical issue Farotimi himself has long criticized.

The delay in granting bail further exacerbates concerns about procedural fairness. Bail is a constitutional right, not a privilege, particularly for non-violent offenses such as defamation. The magistrate’s insistence on a formal bail application suggests either a strategic legal maneuver or judicial discretion potentially influenced by the case’s high-profile nature. A summary bail hearing would have sufficed under normal circumstances, raising legitimate concerns about whether Farotimi is being subjected to undue legal hardship.

Finally, there is a broader concern about the use of law enforcement to enforce what should primarily be a civil matter. The invocation of cyberbullying charges against Farotimi’s supporters also risks blurring the line between legitimate law enforcement and state-backed suppression of dissent. If online criticism is automatically criminalized, Nigeria’s constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech and expression become hollow promises. The state’s duty is to ensure that defamation laws are used to protect reputations without becoming instruments of persecution.

In summation, while Farotimi’s public statements and allegations carry significant legal risks, the manner of his arrest, detention without immediate bail, and invocation of cyberbullying charges against his supporters raise legitimate concerns about due process, jurisdictional overreach, and judicial independence. Until these procedural issues are resolved transparently, the legal proceedings risk being seen as politically motivated and lacking in fairness. The law must be applied uniformly and impartially, regardless of the personalities involved. If Farotimi must face trial, it must be in a court where procedural integrity is beyond reproach and where the truth, rather than influence or power, will prevail.