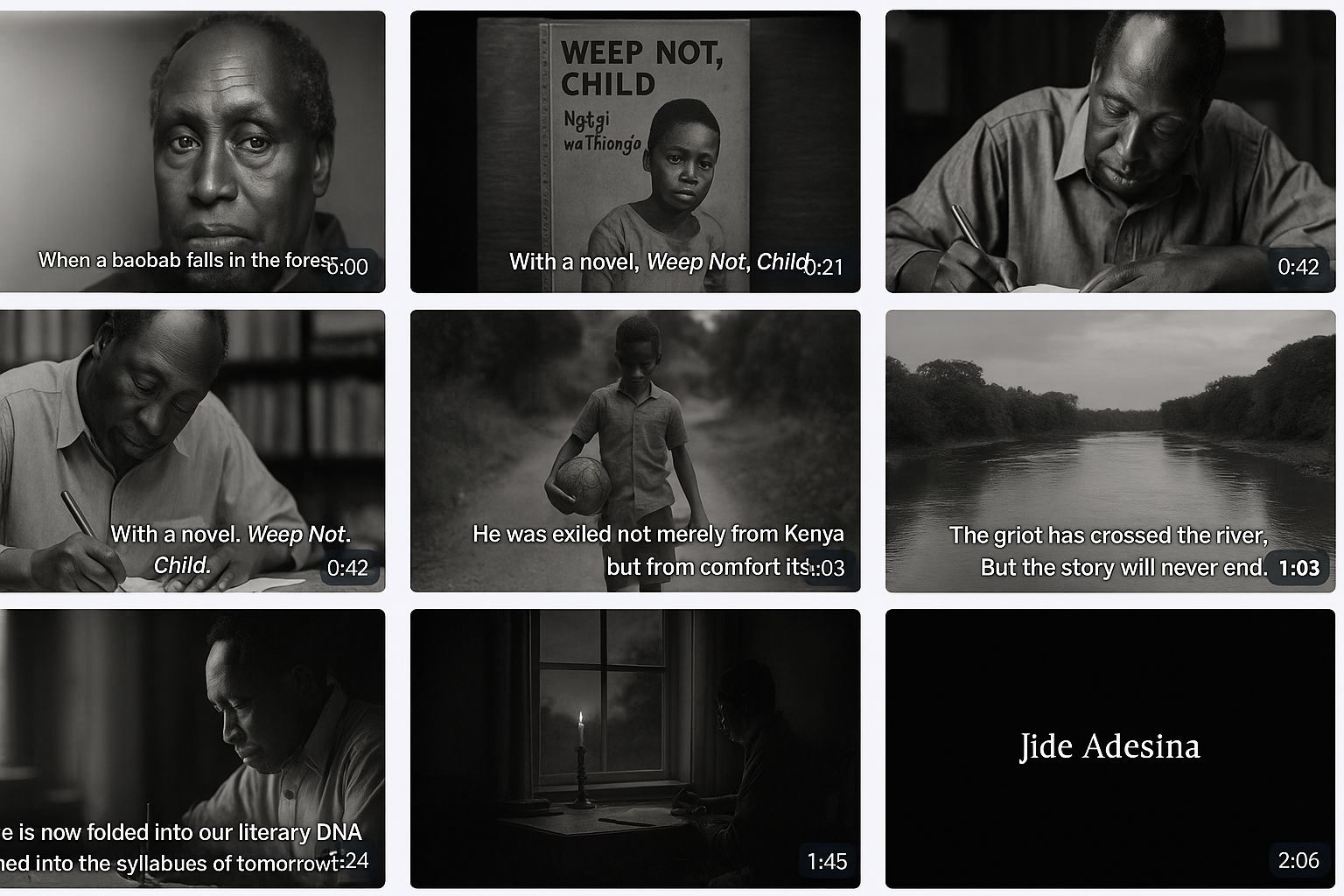

When a baobab falls in the forest, the birds scatter, the light changes, and silence acquires a new grammar.”

When a baobab falls in the forest, the birds scatter, the light changes, and silence acquires a new grammar.”

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o has joined the ancestors.

And we, children of his ink and keepers of his pages, now gather at the intersection of sorrow and reverence—to whisper, to wail, and to write his farewell.

Ngũgĩ was not merely a novelist; he was a continent’s memory in motion, a walking archive of agony and resistance, of laughter layered with loss. He was the griot who bore no drum but thundered through syllables. He taught generations how to wield the pen not just as a tool, but as a machete—cutting through colonial overgrowth, carving open the chest of imperial deception, so that we might examine the wound and name it truth.

He wrote not with ink but with fire drawn from the hearth of his mother tongue—Kikuyu—when he declared war on the colonizer’s grammar, abandoning the English language not out of disdain, but out of devotion. He reclaimed his voice, not for himself, but for us all.

And yet, it began so simply.

With a novel.

Weep Not, Child.

That was my doorway. That was the first flame I carried.

As a teenager, book in one hand and football in the other, I paraded Weep Not, Child like a talisman of thought. I bruised its spine and wore out its corners with rereading. That novel became my hidden anthem—its pages a secret scripture I returned to between goals and exams, between laughter and heartbreak. Even now, I can recall the aching simplicity of its prose, the quiet roar of its rebellion.

Then there was The River Between, whose memory escapes me now like a dream that once mattered but left only its fragrance behind. And I Will Marry When I Want, the audacious play he co-wrote, which I borrowed from Shamsudden, my friend and literary compass—Ngũgĩ’s disciple in every sense. For Shamsudden, Ngũgĩ was not a writer, but a constellation. He spoke of him with the fervour of one defending a god.

And perhaps he was.

A god of the page.

A deity of dissent.

A prophet whose scriptures were inked in exile.

Ngũgĩ was exiled not merely from Kenya but from comfort itself. He walked the lonely path of truth-tellers—threatened, imprisoned, hunted—yet unbowed. His jail cell became a writing desk. His silence, a megaphone.

When he chose to write in Kikuyu, the West recoiled. The Nobel eluded him—perhaps not because he was unworthy, but because he dared to be sovereign. He wrote against empire, not to spite it, but to reclaim what it stole: the African imagination.

And now, the earth of Limuru has reclaimed him.

But not his voice.

That is immortal.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o does not die. He multiplies. He becomes every pen that dares speak in mother tongue. Every child that asks, “Who am I before they named me?” Every rebel who writes under threat, every exile who dreams in verse.

He is now folded into our literary DNA, stitched into the syllables of tomorrow’s writers. He is in the sighs of young boys holding worn books in football-stained hands. He is in the trembling mouths of stage actors shouting, “I Will Marry When I Want!”

So today, we do not mourn as those without inheritance.

We mourn as heirs.

Heirs to a canon carved in courage.

Heirs to a dream no bullet or silence could erase.

Sleep well, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

The griot has crossed the river.

But the story—your story—will never end.

🖋️

Weep not, child… For your father now speaks through the wind.

And the river between us shall carry his words.

Forever.