His Imperial Majesty

Alayeluwa Oba Okunade Sijuwade

(CFR, DCL, LLD, D. LITT)

Olubuse II

OONI of Ife

ONI OF IFE ; OBA SIJUWADE CROSS OVER TO THE HEAVENS @ 85

OBA WA’JA

Oba Sijuwade stood by Opa Oranmiyan on the cradle of his kingdom periscoping the ancient kingdom of Yoruba race . he sails across the ocean and spreads his white sails to the morning breeze , starts for the cool vegetation of the savannah .

He is an epitome civility, authority and power of his kingdom , Ile adulawo , ile odua , Ile kaaro ojire , nibi ti a ‘ti da iwa , iwa baba oro , oro omo sijuwade ! ..

so the emperor gazed with authority and bow to no one but bid the soul to havens and smile at his glorious exist , he fades on the horizon, and someone at other side says, “he is gone”,

Gone where?

Gone to land of his ancestors

Who has left the world better than he found it

His Imperial Majesty

Alayeluwa Oba Okunade Sijuwade Cross of to the heavens

@JIDE ADESINA // THE AFRIKA MARKE

IFE PEOPLE: ANCIENT ARTISTIC, HIGHLY SPIRITUAL AND THE FIRST YORUBA PEOPLE

Ife people celebrating their Obatala festival at Ile IfeThe Ikedu tradition, though unpublicised is the oldest Ife tradition portraying the origin of the Yoruba people and it is clear from this tradition that Oduduwa did not belong to this early period of the emergence of the Yorubas’ as a distinct language group (Olatunji 1996). Okelola (2001) acknowledges that it is hard to establish when the city of Ile-Ife was founded but recognises that Oduduwa was the first King of Ile Ife Kingdom. Akinjogbin (1980),Olatunji (1996) and Adelogun (1999) contrary to Okelola (2001) suggests that there were between ninety three to ninety seven kings who reigned at Ile-Ife before Oduduwa led his people to Ile-Ife. This was confirmed by the archeological evidence unearthed in and around Ile-Ife which dated back to 410 B.C that proves the possibility of human settlement before the advent of Oduduwa (Adelogun 1999). Oduduwa though credited for the establishment of a centralised state at Ife is suggested to have encountered indigenous people in the region (Falola and Heaton, 2008). This centralised state formed by Oduduwa has contributed to the Kingdom of Ile-Ife being the strong hold of indigenous worship as well as the spiritual headquarters of the Yoruba Kingdom (Lucas 1948: Okelola 2001).

Ile ife women in their traditional dress

Ile Ife translated as the spreading of the earth with ‘Ife’ meaning ‘wide’ or and the prefix ‘Ile’ meaning ‘home’ could refer to the creation of the whole world (Smith 1988). Harris (1997) describes Ile-Ife as ‘the place where things spread out, where people left’. There are suggestions that the present Ife town does not stand upon its original site due to difficulty in establishing a coherent account of the past of Ife (Crowder 1962, Smith 1988). Despite the above suggestions Ile Ife is claimed to be the mother city whence all Yoruba people hailed: this is apparent as each princedom were founded and situated few miles from the mother city (Okelola 2001). This myth provides the charter for the Yoruba people, providing them with a sense of unity through a common origin (Bascom 1969). Ile Ife in the Yoruba belief is the oldest of all the Yoruba towns given that it was from Ile Ife that all other towns were founded (Krapf-Askari, 1969). the town provides the fundamental and continuity of great deal of identity conceptualization for the modern Yoruba with it’s role as a center from which Yoruba culture emanates and a place for validation of Yoruba authority (Harris 1997).

Diasporan Ifa priests undergoing their initiation at Ifa temple in Ile Ife, Nigeria

The early written records that mentionss Ife was during the early fourteenth century High Florescence Era when the well-known adventurer, historian and travelor Ibn Battûta(1325–1354) mentioned them in his travelogue. Here we read (1958:409–10) that southwest of the Mâlli (Mali) kingdom lies a country called Yoûfi [Ife?] that is one of the “most considerable countries of the Soudan [governed by a] …souverain [who] is one of the greatest kings.” Battûta’s description of Yoûfi as a country that “No white man can enter … because the negros will kill him before he arrives” appears to reference the ritual primacy long associated with Ife, in keeping with its important manufacturing and mercantile interests, among these advanced technologies of glass bead manufacturing, iron smelting and forging, and textile-production. Blue-green segi beads from Ife have been found as far west as Mali, Mauritania, and modern Ghana, suggesting that Battuta may well have learned of this center in the course of his travels in Mali.

There also appears to be a reference to Ife on a 1375 Spanish trade map known as the Catalan Atlas. This can be seen in the name Rey de Organa, i.e. King of Organa (Obayemi 1980:92),

associated with a locale in the central Saharan region. While the geography is problematic, as was often the case in maps from this era, the name Organa resonates with the title of early Ife rulers,

i.e. Ogane (Oghene, Ogene; Akinjogbin n.d.). The same title is found in a late fifteenth-century account by the Portuguese seafarer Joao Afonso de Aveiro (in Ryder 1969:31), documenting

Benin traditions about an inland kingdom that played a role in local enthronement rituals. While the identity of this inland ruler also is debated, Ife seems to be the most likely referent (see Thornton 1988, among others)

Ife is well known as the city of 401 or 201 deities. It is said that every day of the year the traditional Ifa worshippers celebrate a festival of one of these deities. Often the festivals extend over more than one day and they involve both priestly activities in the palace and theatrical dramatisations in the rest of the kingdom. Because of Ife’s importance in the realm of creation, it has many traditional festivals to commemorate the many deities known in the history of the city and in Yoruba land. The most spectacular festivals demand the King’s participation. These include the Itapa festival for Obatala and Obameri, the Edi festival for Moremi Ajasoro, and the Igare masqueraders, and the Olojo festival for Ogoun. During the festivals and at other occasions the traditional priests offer prayers for the blessing of their own cult-group, the city of Ile Ife, the Nigerian nation and the whole world.

Ile Ifa Ifa practitioners in a street procession in celebration of the anniversary of the Orisha Obatala festival.

The Oòni (or king) of Ife claims direct descent from Oduduwa, and is counted first among the Yoruba kings. He is traditionally considered the 401st deity (òrìshà), the only one that speaks. In fact, the royal dynasty of Ife traces its origin back to the founding of the city more than two thousand years ago. The present ruler is Alayeluwa Oba Okunade Sijuwade, Olubuse II, styled His Imperial Majesty by his subjects. The Ooni ascended his throne in 1980. Following the formation of the Yoruba Orisha Congress in 1986, the Ooni acquired an international status the likes of which the holders of his title hadn’t had since the city’s colonisation by the British. Nationally he had always been prominent amongst the Federal Republic of Nigeria’s company of royal Obas, being regarded as the chief priest and custodian of the holy city of all the Yorubas. In former times, the palace of the Oni of Ife was a structure built of authentic enameled bricks, decorated with artistic porcelain tiles and all sorts of ornaments.

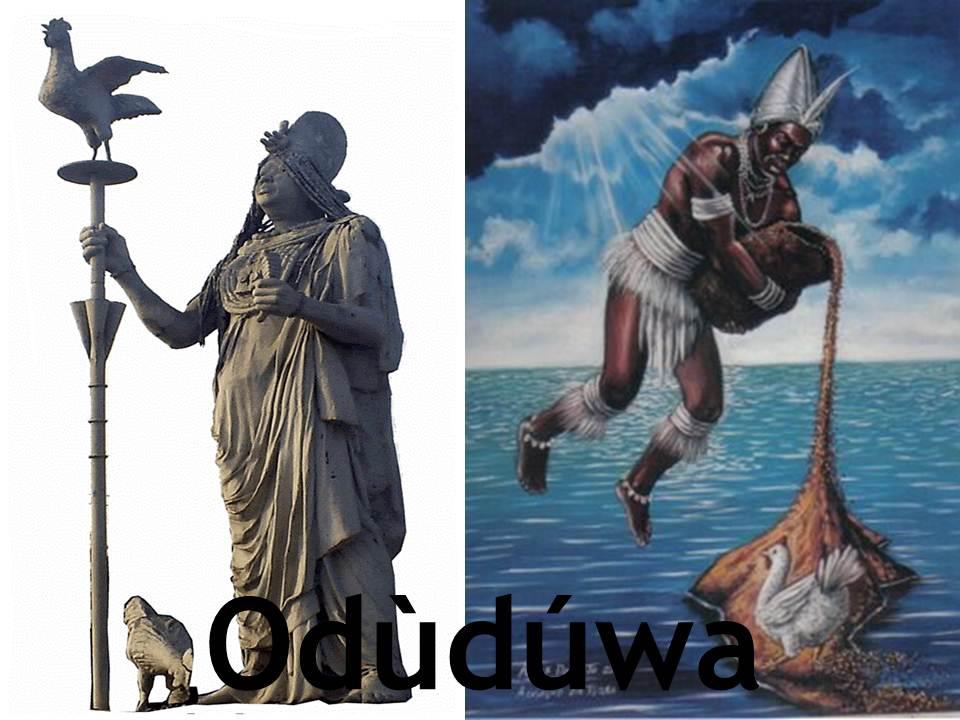

Statue of Oduduwa, the progenitor of Yoruba people

Ife people and their ancient city of Ile Ife which is regarded as the ancient metropolis of Old Yoruba, are so precious and sacred to the Yoruba people so much that every Yoruba sub-group is forbidden to attack them no matter how they provoke a particular sub-group. Attacking an Ife citizen or Ile Ife town is an abomination, high treason and sacrilegious act that can lead to complete extermination of a particular Yoruba group, as all other Yoruba groups will come together to fight against any Yoruba that fight or attack Ife citizen or towns. The case in point is how combined Yoruba forces led by Ijebu, Ife and their allies completely destroyed the original habitat of Orile-Owu or Owu-Ipole and their Ikija allies forcing them to flee to seek sanctuary at Abeokuta among the Egbas, when Owu people under the leadership of Olowu Amororo attacked Ife towns. The result result of Olowu`s action became a disaster for the Owu people in their original abode and threw the whole of Yoruba land into civil war. In fact, the Owu were thoroughly defeated by the combined forces of Ibadan and Ijebu, and the Oni of Ife, the spiritual head of the Yorubas, ordered with his constitutional authority, that the Owu capital, Orile-Owu must be destroyed with no human existence. According to Samuel Johnson in his renowned book “The History of the Yoruba” Owu was rendered helpless as famine emerged and they “began for the first time to eat those large beans called popondo (or awuje) hitherto considered unfit for food; hence the taunting songs of the allies : —

“Popondo I’ara Owu nje. (The Owus now live on propondo)

Aje f’ajaga bo ‘run.” (That done, their necks for the yoke)

Unto this day, whoever would hum this ditty within the hearing of an Owu man, must look out for an accident to his own person. Ikija was the only Egba town which befriended the city of Owu in her straits hence after the fall of the latter town, the combined armies went to punish her for supplying Owu with provisions during the siege. Being a much smaller town, they soon made short work of it. After the destruction of Ikija,^ the allies returned to their former camp at Idi Ogungun (under the Ogiingun tree). “Owu was thenceforth placed under an interdict, never to be rebuilt ; and it was resolved that in future, however great might be the population of Oje — the nearest town to it — the town walls should not extend as far as the Ogungun tree, where the camp was pitched. Consequently to this day, although the land may be cultivated yet no one is allowed to build a house on it.” (Johnson, 1928)

According to Fashogbon (1995) recounting the oral historical handout of the ancient Yoruba town of Ile-Ife submits that “it is the first creation in this world”. Ile-Ife is the holy city, the home of divinities and mysterious spirits, the source of all oceans and the gateway to heaven. A school of thought even speculates that Ile-Ife was the seat of civilization from where Egypt received its civilization which later spread to the Hebrews and the Babylonians then to the Chaldeans, the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans and finally to the Britons (Fabunmi, 1969).

Ile-Ife’s prominence in the ritual system like ‘Ifa’ and ‘Ijala’ has helped in preserving the city’s significance in Yoruba culture despite its political decline. Generally, therefore, Ile-Ife has earned many enviable appellations, viz:

Ile-Ife, ile Owuro Ile-Ife, the land of the most ancient days

Ile-Ife, Oodaye Ile-Ife, where the word of creation took place

Ile-Ife, Ibi ti ojumo ti mowa Ile-Ife, where the dawn of the day was first experienced

Ile-Ife, Ori aye gbogbo Ile-Ife, head of the whole universe

Ile-Ife, Ooye Lagbo Ile-Ife the city of the Survivors.

(Fashogbon, op.cit)

Yoruba oral history even testifies to it that Oduduwa the progenitor of the Yoruba, and other ‘Leaders of Mankind’ (deities and divinities) were the Survivors (Ooye Lagbo) after the deluge and that they were the founders of Ile-Ife whence the people migrated to the different territories they presently occupy (Fashogbon, 1995).

Yoruba people see Ife as a place where the founding deities Oduduwa and Obatala began the creation of the world, as directed by the paramount deity Olodumare. Obàtálá created the first humans out of clay, while Odùduwà became the first divine king of the Yoruba. But it must be emphasised that Oduduwa and Obatala met aboriginal people on the land. Regardless of the considerable differences between the various Yoruba myths as to which deity could claim to be the world’s creator, all agree on one factor, the presence of a hunter named Ore at the time. In the most widespread account, when Odudua came down to create the Earth, he found that Ore, an aboriginal hunter, was already established there (Idowu, 23). In the major opposing legend, in which Obatala is credited with creating the world, Ore (Oreluere) is said to have come down with the first party that Obatala sent to Earth (Idowu, 20). Both versions express concern for a legitimate claim to the Ife lands (i.e., creation of) and, in turn, control over them. Though the accounts differ as to the creator (Odudua or Obatala), they both indicate that the hunter Ore (Oreluere) had rightful claim to the land. Interestingly, according to T. J. Bowen (Adventures and Missionary Labours in Several Countries in the Interior of Africa from 1849 to 1956, London, 1857, 267), the “great mother” of the Yoruba is worshipped under the name of Iymmodeh (Iya ommoh Oddeh) “the mother of the hunter’s [i.e., Ore’s] children.”

Yoruba religious history, emerged most likely in the aftermath of the establishment of Ife’s second dynasty in about 1300 CE when many of Ife’s famous early arts appear to have been made, a period closely identified with King Obalufon II. This ruler is credited not only with bringing peace to this center, and with commissioning an array of important arts (bronze casting, beaded regalia, weaving), but also with a new city plan in which the palace and market are located in the center surrounded by various religious sanctuaries arrayed in relationship to it. This plan features four main avenues leading into the city, each roughly running along a cardinal axis through what were once manned gates that pierced the circular city walls at points broadly consistent with the cardinal directions. The plan of Ile-Ife, which may have housed some 125,000 inhabitants in that era, offers important clues into early Yoruba views of both cosmology and directional primacy.

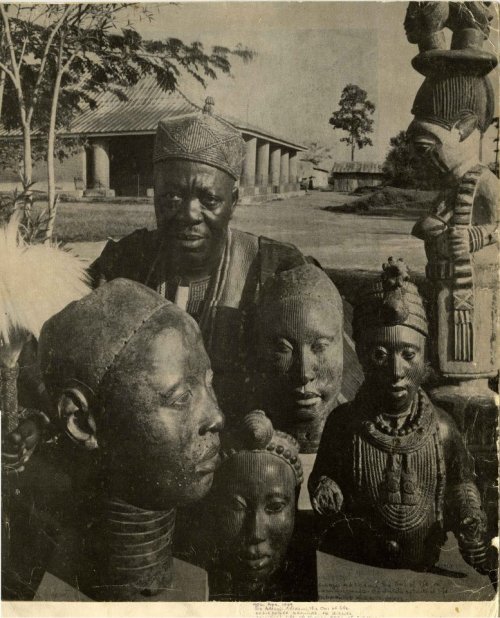

In Ife artistic works, important people were often depicted with large heads because the artists believed that the Ase was held in the head, the Ase being the inner power and energy of a person. Their rulers were also often depicted with their mouths covered so that the power of their speech would not be too great. They did not idealize individual people, but they tended rather to idealize the office of the king. The city was a settlement of substantial size between the 9th and 12th centuries, with houses featuring potsherd pavements. Ilé-Ifè is known worldwide for its ancient and naturalistic bronze, stone and terracotta sculptures, which reached their peak of artistic expression between 1200 and 1400 A.D. After this period, production declined as political and economic power shifted to the nearby kingdom of Benin which, like the Yoruba kingdom of Oyo, developed into a major empire.

Bronze and terracotta art created by this civilization are significant examples of realism in pre-colonial African art.

In his book, “The Oral Traditions in Ile-Ife,” Yemi D. Prince referred to the terracotta artists of 900 A.D. as the founders of Art Guilds, cultural schools of philosophy, which today can be likened to many of Europe’s old institutions of learning that were originally established as religious bodies. These guilds may well be some of the oldest non-Abrahamic African centres of learning to remain as viable entities in the contemporary world. A major exhibition entitled Kingdom of Ife: Sculptures of West Africa, displaying works of art found in Ife and the surrounding area, was held in the British Museum from 4 March to 4 July 2010.

Today a mid-sized city, Ife is home to both the Obafemi Awolowo University and the Natural History Museum of Nigeria. Its people are of the Yoruba ethnic group, one of the largest ethnolinguistic groups in Africa and its diaspora (The population of the Yoruba outside of their homeland is said to be more than the population of Yoruba in Nigeria, about 35 million).[citation needed] Ife has a local television station called NTA Ife, and is home to various businesses. It is also the trade center for a farming region where yams, cassava, grain, cacao, and tobacco are grown. Cotton is also produced, and is used to weave cloth. Hotels in Ilé-Ife include Cameroon Hotel, Hotel Diganga Ife-Ibadan road, Mayfair Hotel, Obafemi Awolowo University Guest House etc. Ilé-Ife has a stadium with a capacity of 9,000 and a second division professional league football team.

The Orunmila Barami Agbonmiregun, the World Ifa Festival was held Saturday June 4-5, 2011 at Oketase the World Ifa Temple, Ile-Ife.

Mythic origin of Ife, the holy city: Creation of the world

The Yoruba claim to have originated in Ife. According to their mythology, Olodumare, the Supreme God, ordered Obatala to create the earth but on his way he found palm wine, drank it and became intoxicated. Therefore the younger brother of the latter, Oduduwa, took the three items of creation from him, climbed down from the heavens on a chain and threw a handful of earth on the primordial ocean, then put a cockerel on it so that it would scatter the earth, thus creating the land on which Ile Ife would be built. Oduduwa planted a palm nut in a hole in the newly formed land and from there sprang a great tree with sixteen branches, a symbolic representation of the clans of the early Ife city-state.

The usurpation of creation by Oduduwa gave rise to the ever lasting conflict between him and his elder brother Obatala, which is still re-enacted in the modern era by the cult groups of the two clans during the Itapa New Year festival. On account of his creation of the world Oduduwa became the ancestor of the first divine king of the Yoruba, while Obatala is believed to have created the first humans out of clay. The meaning of the word “ife” in Yoruba is “expansion”; “Ile-Ife” is therefore in reference to the myth of origin “The Land of Expansion”. Due to this fact, the city is commonly regarded as the cradle of not just the Yoruba culture, but all of humanity as well, especially by the followers of the Yoruba faith.

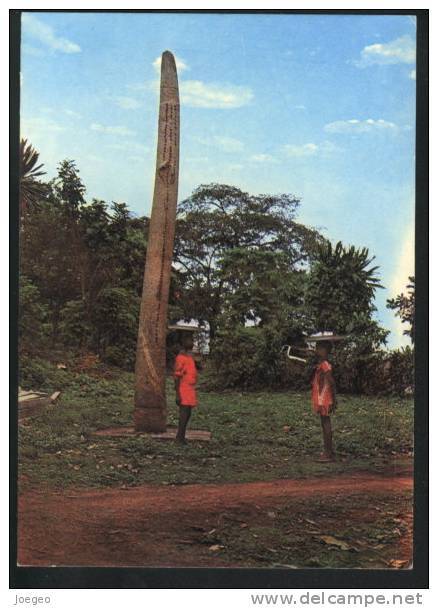

Oduduwa had sons, daughters and a grandson who went on to found their own kingdoms and empires, namely Ila Orangun, Owu, Ketu, Sabe, Popo, Oyo and Benin. Oranmiyan, Oduduwa’s last born, was one of his father’s principal ministers and overseer of the nascent Edo empire after Oduduwa granted the plea of the Edo people for his governance. When Oranmiyan decided to go back to Ile Ife after a period of service in Benin, he left behind a child named Eweka that he had in the interim with an indigenous princess. The young boy went on to become the first legitimate ruler of the second Edo dynasty that has ruled what is now Benin from that day to this. Oranmiyan later went on to found the Oyo empire that stretched at its height from the western banks of the river Niger to the Eastern banks of the river Volta. It would serve as one of the most powerful of Africa’s medieval states prior to its collapse in the 19th century.

Language

The people of Ife speak a unique and authentic Central Yoruba (CY) dialect of Yoruba language which belongs to the larger Niger-Congo language family. Apart from Ife, the other Yoruba sub-groups that speak Central Yoruba (CY) dialects are Igbomina, Yagba, Ilésà, Ekiti, Akurẹ, Ẹfọn, and Ijẹbu areas.

History of Ife Kingdom

In the southern forested region of Nigeria, the largest centralized states were the kingdoms centered on Ile-Ife and Benin which emerged by 1500 CE and the origins of the Ife natives are lost in antiquity (Falola and Heaton 2008, Osasona et al 2009). According to Biobaku (1955) the town was probably founded between the 7th and 10th centuries AD; Jeffrey (1958) opines that it had become a flourishing civilization by the 11th Century. Carbon-dating yielded from work of archaeologists appears to support these views, as it establishes that Ile Ife “was a settlement of substantial size between the 9th and 12th centuries” (Willett, 1971:367, Smith 1988). Drewal et al (1998)also suggested that the site of Ile–Ife was occupied as early as 350 B.C. and consisted of a cluster of hamlets; though little is known about the early occupants except for a city wall at Enuwa and later the construction of another outer city wall. Traditionally, Ile-Ife was divided into five quarters namely Iremo, Okerewe, Moore, Ilode and Ilare and within each quarter were compounds with family lineages (Eluyemi 1978). The traditional Ife kingdom, schematically, could be described as a wheel, with the Oba’s palace as the hub, from which roads radiated like spokes and in relation to which the en-framing town wall represented the rim (Krapf-Askari, 1969; Obateru, 2006). Ile–Ife is regarded therefore as the metropolis of old Yoruba. Though suggested by various scholars including Johnson (1921); Lucas (1948); and Ajayi and Crowther (1972) that Ile-Ife is fabled as the spot where God created man, white and black and from whence they dispersed all over the earth it is yet to be scientifically proven. Fabunmi (1969) further argued that Ile Ife is further regarded and believed to be the cradle of the world. The history of Ile Ife though unwritten is based on oral traditions and referred to as the original home of all things, the place where the day dawns; the holy city, the home of divinities and mysterious spirits (Okelola, 2001). It is however believed that the tradition of the world and of the origin of the peoples and their state centers on Ile Ife, the source whence all the major rulers of the then southern Nigeria derive the sanctions of their kingship where gods, shrines and festivals forms the center of religion (Smith 1988).

Ile Ife translated as the spreading of the earth with ‘Ife’ meaning ‘wide’ and the prefix ‘Ile’ meaning ‘home’ could refer to the creation of the whole world (Smith 1988). Harris (1997) describes Ile-Ife as ‘the place where things spread out, where people left’. There are suggestions that the present Ife town does not stand upon its original site due to difficulty in establishing a coherent account of the past of Ife (Crowder 1962, Smith 1988). Despite the above suggestions Ile Ife is claimed to be the mother city whence all Yoruba people hailed: this is apparent as each princedom were founded and situated few miles from the mother city (Okelola 2001). This myth provides the charter for the Yoruba people, providing them with a sense of unity through a common origin (Bascom 1969). Ile Ife in the Yoruba belief is the oldest of all the Yoruba towns given that it was from Ile Ife that all other towns were founded (Krapf-Askari, 1969). the town provides the fundamental and continuity of great deal of identity conceptualization for the modern Yoruba with it’s role as a center from which Yoruba culture emanates and a place for validation of Yoruba authority (Harris 1997). There was a monarch called Ogane who reigned in ancient Ife whom modern scholars have identified as the Ooni of Ife (Pereira 1937, Krapf-Askari 1969, Harris, 1997). The Ooni or Onife is regarded as the spiritual head of the Yoruba whose influence was not confined to his own kingdom but was also exercised over other Yoruba kingdoms through the sanctions of kinship and by ancient constitutional devices (Smith 1988). The Ooni is believed to be a sacred being because he sits on the throne of Oduduwa at Ile-Ife.

Statue of Moremi at Moremi Hall (UNILAG) . Moremi was the wife of Oranmiyan. A woman of tremendous beauty and a faithful and zealous supporter of her husband and the Kingdom of Ile Ife.

The Ikedu tradition, though unpublicised is the oldest Ife tradition portraying the origin of the Yoruba people and it is clear from this tradition that Oduduwa did not belong to this early period of the emergence of the Yorubas’ as a distinct language group (Olatunji 1996). Okelola (2001) acknowledges that it is hard to establish when the city of Ile-Ife was founded but recognises that Oduduwa was the first King of Ile Ife Kingdom. Akinjogbin (1980),Olatunji (1996) and Adelogun (1999) contrary to Okelola (2001) suggests that there were between ninety three to ninety seven kings who reigned at Ile-Ife before Oduduwa led his people to Ile-Ife. This was confirmed by the archeological evidence unearthed in and around Ile-Ife which dated back to 410 B.C that proves the possibility of human settlement before the advent of Oduduwa (Adelogun 1999). Oduduwa though credited for the establishment of a centralised state at Ife is suggested to have encountered indigenous peop,le in the region (Falola and Heaton, 2008). This centralised state formed by Oduduwa . has contributed to the Kingdom of Ile-Ife being the strong hold of indigenous worship as well as the spiritual headquarters of the Yoruba Kingdom (Lucas 1948: Okelola 2001).

The city of Ile-Ife today sits in what is today Osun State in southern Nigeria located on the longitude 4.6N and 7.5°N, surrounded by hills and is about fifty miles (80.467kms) to Ibadan and Osogbo (Philips, 1852; White, 1876). The city popularly known to as Ile-Ife and the people are referred to as ‘Ife’ who also refer to the town as ‘Ife’ or ‘Ilurun’ which means ‘the gateway to heaven’ (Eluyemi 1986:16). Confirmed to be situated on the site of ancient Ile Ife due to the location of the seven brass castings excavated from the ancient Ife sites which were in corresponding stratigraphic positions confirming that a settlement of substantial size existed there between the ninth and twelfth centuries (Willet, 1967). He also confirmed that the terracotta sculpture and lost wax (cire-perdue) castings were made there from early in the present millennium. Ile-Ife’s prominence in the ritual system like ‘Ifa’ and ‘Ijala’ has helped in preserving the city’s significance in Yoruba culture despite its political decline.

Freedom’ ceremony. Taken at Ile-Ife in present day Osun State. 1968. Freedom ceremonies marked women’s graduation into professions such as nursing and tailoring

Among the first of the Ife works to reach the West were those brought to Europe by the British colonial governor Gilbert Thomas Carter. According to Samuel Johnson (p. 647) “three of those national and ancestral works of art known as the ‘Ife marbles’ “were given to Carter in 1896 by

Adelekan, the then recently crowned king of Ife. Johnson explains that the king gave them to Governor Carter in an effort to gain a positive decision concerning the resettlement of Modakeke residents outside the city.

Past Ooni of Ife

1ST ODUDUWA

2ND OSANGANGAN OBAMAKIN

3RD OGUN

4TH OBALUFON OGBOGBODIRIN

5TH OBALUFON ALAYEMORE

6TH ORANMIYAN

7TH AYETISE

8TH LAJAMISAN

9TH LAJODOOGUN

10TH LAFOGIDO

11TH ODIDIMODE ROGBEESIN

12TH AWOROKOLOKIN

13TH EKUN

14TH AJIMUDA

15TH GBOONIJIO

16TH OKANLAJOSIN

17TH ADEGBALU

18TH OSINKOLA

19TH OGBORUU

20TH GIESI

21ST LUWOO (FEMALE)

22ND LUMOBI

23RD AGBEDEGBEDE

24TH OJELOKUNBIRIN

25TH LAGUNJA

26TH LARUNNKA

27TH ADEMILU

28TH OMOGBOGBO

29TH AJILA-OORUN

30TH ADEJINLE

31ST OLOJO

32ND OKITI

33RD LUGBADE

34TH ARIBIWOSO

35TH OSINLADE

36TH ADAGBA

37TH OJIGIDIRI

38TH AKINMOYERO

1770-1800

39TH GBANLARE

1800-1823

40TH GBEGBAAJE

1823-1835

41ST WUNMONIJE

1835-1839

42ND ADEGUNLE ADEWELA

1839-1849

43RD DEGBINSOKUN

1849-1878

44TH ORARIGBA

1878-1880

45TH DERIN OLOGBENLA- He was a powerful warrior!

1880-1894

46TH ADELEKAN (OLUBUSE I)- He was the first Ooni to travel outside Ile-Ife to

Lagos in 1903 when he was invited by the then Governor General to settle the

dispute involving Elepe of Epe. All Yoruba Kings including the Alaafin left

their respective thrones as a mark of respect for the Ooni. They returned to

their respective stools after Ooni returned to Ile-Ife from Lagos. Oba Adelekan

Olubuse was nicknamed ‘ERIOGUN’; Akitikori; Ebitikimopiri.

1894-1910

47TH ADEKOLA

1910-1910

48TH ADEMILUYI (AJAGUN) – He also was reputed to be a powerful Monarch.

1910-1930

49TH ADESOJI ADEREMI- Very intelligent with good foresight, he was invited to be

minister without portfolio when he ruled from 1951 to 1955. He was the first

indigenous governor of Western Nigeria. One of his most laudable achievements

was the establishment of the GREAT University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo

University) at Ile-Ife.

1930-1980

50TH OKUADE SIJUWADE II – 1980-2015

His Royal Highness, Aleyeluwa, Oba Okunade Sijuade, Olubuse II, The Oni of Ife, Ile Ife, Osun State, arriving at the National Museum, Onikan Lagos for the opening ceremony in his car, on Friday, May 18, 2012..

Religion

Like most towns, the people are religion conscious. The three main religions in the city are Christianity, Islam and traditional. Traditional religion appears flourishing than the other two as most people who belong to either of the former two also have soft spot for the age-long religion. So being a Christian or a Moslem does not preclude you from the traditional religion, which the elders hold in high esteem. It is not uncommon to be a leader in a denomination and still hold chieftaincy title that has to do with shrine.

Here, Olojo is the biggest festival on the Ife cultural calendar. This festival is held annually to commemorate Oduduwa’s descent from heaven. It is during the Olojo festival that Ooni wears Aare crown. Aare is a mysterious crown worn only once in a year and it is believed to possess the power that instantly transfigure Ooni to the rank of Orisa (god). With 201 traditional religious festivals, it is only one day that is free that the people do not offer sacrifice at the various shrines that dot the town. This particular day remains a secret the chief and priests of the kingdom keep so dear to the heart.

Ifa is another sect that attracts good number of the people. Unlike what obtains in most other towns where Ifa worship is individualized and confined to illiterate priests or Babalawo in ramshackled buildings, it has been modernised such that one may mistake its worship centre for a church. Incidentally, their worship session is on Sunday like their Christian counterparts. When Sunday Sun visited the imposing Ifa Auditorium on top of a hill, near Ife Town Hall, children were seen playing unmolested. The children admitted that they also worship in the Ifa hall along with the elders. The main auditorium is the Headquarters of Ifa Worship Worldwide, which was being prepared to host a meeting of all worshippers round the globe last month. Araba is the chief priest.

Some of the main gods they worship include Obatala, Ogun, Olokun, Orunmila, Olojo, Sango, Ifa, Osun, Ela, Oya, Yemoja, Oranmiyan. These are what they call ‘sky gods’ that control virtually everything on earth. Many hold that Ife is a fetish town ruled by powers of darkness, but the chiefs and leaders of the town think otherwise. Such views to them can only be from one who is mentally unstable.

One of the oldest Stone buildings in Ile-Ife is the beautifully preserved Seventh Day Adventist church built over a 100 years ago.

Dressing

The people love dressing well in either their native attire or westernized way. Though English garb has eroded the traditional pattern of dressing like in other Nigerian cities, native wears are still prevalent among the middle age and the elderly. When an Ife man puts on Buba, he dons cap to complete the dressing. The women are even more compliant in matters of tradition. Though Chief Ijaodola claimed that Aso Ofi is the main custume of his people, Ankara fabric is the commonest textile of the people today. The Ooni himself is an example in splendid sartorial taste. Each time he comes out, he is pleasant to behold in his expensive apparel.

One thing very noticeable in the dressing of Ife people is that a high sense of discipline and morality is still displayed. It is almost impossible to see a lady-young or old in revealing clothes or in one that shows the upper or lower cleavage. Not even with Ife being a university town will one see beckoning types of dressing on its streets.

Sola Omisore has an explanation for the decent dressing. “Discipline is instilled through family lineage. We know ourselves. So if a lady dresses indecently, people will say: Is this not the child of so so? Don’t think because Ife is a city that we don’t know ourselves.”

Art in Ancient Ife, Birthplace of the Yoruba

Suzanne Preston Blier

Artists the world over shape knowledge and material into works of unique historical importance. The artists of ancient Ife, ancestral home to the Yoruba and mythic birthplace of gods and humans, clearly were interested in creating works that could be read. Breaking the symbolic code that lies behind the unique meanings of Ife’s ancient sculptures, however, has vexed scholars working on this material for over a century. While much remains to be learned, thanks to a better understanding of the larger corpus of ancient Ife arts and the history of this important southwestern Nigerian center, key aspects of this code can now be discerned. In this article I explore how these arts both inform and are enriched by early Ife history and the leaders who shaped it.1 In addition to

core questions of art iconography and symbolism, I also address the potent social, political, religious, and historical import of these works and what they reveal about Ife (Ile-Ife) as an early

cosmopolitan center.

My analysis moves away from the recent framing of ancient Ife art from the vantage of Yoruba cultural practices collected in Nigeria more broadly, and/or the indiscriminate use of regional and modern Yoruba proverbs, poems, or language idioms to inform this city’s unique 700-year-old sculptural oeuvre. Instead I focus on historical and other considerations in metropolitan Ife itself. This shift is an important one because Ife’s history, language, and art forms are notably different than those in the wider Yoruba region and later eras. My approach also differs from recent studies that either ahistorically superimpose contemporary cultural conventions on the reading of ancient works or unilinearly posit art development models concerning form or material differences that lack grounding in Ife archaeological evidence. My aim instead is to reengage these remarkable ancient works alongside diverse evidence on this center’s past and the time frame specific to when these sculptures were made. In this way I bring art and history into direct engagement with each other, enriching both within this process.

One of the most important events in ancient Ife history with respect to both the early arts and later era religious and political traditions here was a devastating civil war pitting one group, the supporters of Obatala (referencing today at once a god, a deity pantheon, and the region’s autochthonous populations) against affiliates of Odudua (an opposing deity, religious pantheon, and newly arriving dynastic group). The Ikedu oral history text addressing Ife’s history (an annotated kings list transposed from the early Ife dialect; Akinjogbin n.d.) indicates that it was during the reign of Ife’s 46th king—what appears to be two rulers prior to the famous King Obalufon II (Ekenwa? Fig. 1)—that this violent civil war broke out. This conflict weakened the city enough so that there was little resistance when a military force under the conqueror Oranmiyan (Fig. 2) arrived in this historic city. The dispute likely was framed in part around issues of control of Ife’s rich manufacturing resources (glass beads, among these). Conceivably it was one of Ife’s feuding polities that invited this outsider force to come to Ife to help rectify the situation for their side.

As Akinjogbin explains (1992:98), Oranmiyan and his calvary, after gaining control of Ife “… stemmed the … uprising by siding with the weaker … of the disunited pre-Oduduwa groups .…

[driving Obalufon II] into exile at Ilara and became the Ooni.” Eventually, the deposed King Obalufon II with the help of a large segment of Ife’s population was able to defeat this military

leader and the latter’s supporters. In Ife today, Odudua is identified in ways that complement Oranmiyan. As Akintitan explains (p.c.): “It was Odudua who was the last to come to Ife, a man

who arrived as a warrior, and took advantage of the situation to impose himself on Ife people.” King Obalufon II, who came to rule twice at Ife, is positioned in local king lists both at the end

of the first (Obatala) dynasty and at the beginning of the second (Odudua) dynasty. He is also credited with bringing peace (a negotiated truce) to the once feuding parties.

Political History and Art at Ancient Ife

What or whom do these early arts depict? Many of the ancient Ife sculptures are identified today with individuals who lived in the era in which Ife King Obalufon II was on the throne and/

or participated in the civil war associated with his reign. This and other evidence suggests that Obalufon II was a key sponsor or patron of these ancient arts, an idea consistent with this

king’s modern identity as patron deity of bronze casting, textiles, regalia, peace, and wellbeing. It also is possible that a majority of the ancient Ife arts were created in conjunction with the famous

truce that Obalufon II is said to have brokered once he returned to power between the embattled Ife citizens as he brought peace to this long embattled city (Adediran 1992:91; Akintitan p.c.).

As part of his plan to reunite the feuding parties, Obalufon II also is credited with the creation of a new city plan with a large, high-walled palace at its center. Around the perimeters, the compounds of key chiefs from the once feuding lineages were positioned. King Obalufon II seems at the same time to have pressed for the erection of new temples in the city and the refurbishment of older ones, these serving in part to honor the leading chiefs on both sides of the dispute. Ife’s ancient art works likely functioned as related temple furnishings.

One particularly art-rich shrine complex that may have come into new prominence as part of Obalufon II’s truce is that honoring the ancient hunter Ore, a deity whose name also features

in one of Obalufon’s praise names. Ore is identified both as an important autochthonous Ife resident and as an opponent to “Odudua.” A number of remarkable granite figures in the Ore

Grove were the focus of ceremonies into the mid-twentieth century. One of these works called Olofefura (Fig. 4) is believed to represent the deified Ore (Dennett 1910:21; Talbot 1926 2:339;

Allison 1968:13). Features of the sculpture suggest a dwarf or sufferer of a congenital disorder in keeping with the identity of many first (Obatala) dynasty shrine figures with body anomalies or disease. Regalia details also offer clues. A three-strand choker encircles Olofefura’s neck; three bracelet coils embellish the wrist; three tassels hang from the left hip knot. These features link this work—and Ore—to the earth, autochthony, and to the Ogboni association, a group promoted by Obalufon II in part to preserve the rights of autochthonous residents.

The left hip knot shown on the wrapper of this work, as well as that of the taller, more elegant Ore Grove priest or servant figure (Fig. 5), also recalls one of Ife’s little-known origin myths within the Obatala priestly family (Akintitan p.c.). According to this myth, Obatala hid the ase (vital force) necessary for Earth’s solidity within this knot, requiring his younger brother Odudua, after his theft of materials from Obatala, to wait for the latter’s help in completing the task. Consistent with this, Ogboni members are said to tie their cloth wrappers on the left hip in memory of Obatala’s use of this knot to safeguard the requisite ase (Owakinyin p.c.). Iron inserts in the coiffure of the taller Ore figure complement those secured in the surface of the Oranmiyan staff (Fig. 2), indicating that this sculpture—like many ancient Ife works of stone—were made in the same era, e.g. the early

fourteenth century.

An additional noteworthy feature of these figures, and others, is the importance of body proportion ratios. Among the Yoruba today, the body is seen to comprise three principal parts: head, trunk, and legs (Ajibade n.d.:3). Many Ife sculptural examples (see Fig. 4; compare also Figs. 15–16) emphasize a larger-thanlife size scale of the head (orí) in relationship to the rest of the body (a roughly 1:4 ratio). Yoruba scholars have seen this headprivileging ratio as reinforcing the importance of this body part as a symbol of ego and destiny (orí), personality (wú), essential

nature (ìwà), and authority (àse) (Abimbola 1975:390ff, Abiodun 1994, Abiodun et. al 1991:12ff).6 Or as Ogunremi suggests (1998:113), such features highlight: “The wealth or poverty of the nation … [as] equated with the ‘head’ (orí) of the ruler of a particular locality.”

Both here and in ancient Ife art more generally, however, there is striking variability in related body proportions. Such ratios range from roughly 1:4 for the Ore grove deity figure (Fig. 4), the complete copper alloy king figure (Fig. 15), the couple from Ita Yemoo (Fig. 8), and many of the terracotta sculptures, to roughly 1:6 for the taller stone Ore grove figures (Fig. 5) and the copper seated figure from Tada (Fig. 11). Why these proportional differences exist in Ife art is not clear, but issues of class and/or status appear to be key. Whereas sculptures of Ife royals and gods often show 1:4 ratios, most nonroyals show proportions much closer to life. In ancient Ife art, the higher the status, the greater likelihood that body proportions will differ from nature in ways that greatly enhance the size of the head. This not only highlights the head as a prominent status and authority marker, but also points to the primacy of social difference in visual rendering.

While many Ife (and Yoruba) scholars have focused on how the head is privileged in relationship to the body, what also is important, and to date overlooked, is that the belly is equally important. The full, plump torsos (chest and stomachs) of Ife figures depicting rulers and deities complement modern Yoruba beliefs about health and well being on the one hand, and wealth and power on the other. Related ideas are suggested by the modern Yoruba term odù (“full”) which, when applied to an individual, means both “he has blessing in abundance” and “fortune shines on him”(Idowu 1962:33). A full belly is vital to royals and deities not only as a reference to qualities of wellbeing but also as markers of state and religious fullness. In his extended discussion of the concept of odù, the indigenous Ife religious scholar Idowu notes (1962:33) that the same term also indicates a “very

large and deep pot (container)” and by extension anything that is of “sizable worth” and/or “superior quality.” This word features centrally in the name for the high god, Ol-odù-marè. According to Idowu (1962:34) the latter use of the term signifies “He is One who is superlative,” odù here invoking his very extraordinariness. Because large ceramic vessels called odù were employed in ancient Ife contexts as containers for highly valued goods such as beads and art (including the Ita Yemoo king figure, Fig. 16), this idiom offers an interesting modern complement and descriptor for early Ife sculptural portrayals of gods and kings as containers holding many benefits. A complementary feature of many ancient Ife works is that of composure or inner calm (àìkominún, “tranquility of the mind” in modern Yoruba; Abraham 1958:388). This notable quality finds potential expression through the complete repose shown in their faces of early Ife art (Figs. 1, 15, 16), a quality that increases the sense of monumentality and power in these remarkable works.

The ancient Ife arts from Ife’s Ore shrine, which appear to have been carved as a single sculptural group, include a stone vessel with crocodiles on its sides (Fig. 6). On its lid a frog (or toad) is shown in the jaws of a snake. The latter motif references the contestation between Obatala and Odudua for the center’s control (Akintitan p.c.; Adelekan p.c.). According Akintitan (p.c.), this design addresses the less-than-straight manner in which Odudua asserted control over Ife, since poisonous snakes are thought not to consume frogs (and toads). The crocodile, like several other animal figurations from this grove, honor Ore’s hunting and fishing prowess. Carved crocodiles, giant eggs, a mudfish (African lung fish), and an elephant tusk reference the watery realm that dominated primordial Ife. A granite slab from this same site shows evenly placed holes (Fig. 7). This work served perhaps as a real or metaphoric measuring device for Ife’s changing water levels, in keeping both with frequent flooding here (referenced in local accounts about Obalufon II’s wife

Queen Moremi) as well as Ife origin myths in which the Earth is said to have been formed only after Odudua sprinkled dirt upon the water’s surface (Idowu 1962, Blier 2004). One especially striking art-rich Ife site that also seems to have been identified with Obalufon II and his famous political truce is Ita Yemoo, the term yemoo serving as the title for first dynasty Ife queens. This temple complex lies near the site where the annual Edi festival terminates. The Edi ritual is dedicated to Obalufon II’s wife, Moremi, who also at one time was married to Obalufon II’s adversary, the conqueror Oranmiyan. One of the most striking works from Ita Yemoo is a copper alloy casting of a king and queen (Fig. 8) with interlocked arms and legs. The male royal wears a simian skull on his hip, a symbol of Obatala (monkeys evoking the region’s early occupants) and this deity’s identity with Ife’s autochthonous residents and first dynasty line. The female points toward the ground, gesturing toward Odudua as both second dynasty founder and later Yoruba earth god. This royal couple appears to reference in this way not only the painful Ife dynastic struggle between competing Ife families and chiefs, but also the political and religious marriage promoted by Obalufon II between the these groups as part of his truce. Interestingly, a steatite head recovered by Frobenius at Offa (Moremi’s hometown north of Ife) wears a similar queen’s crown. Offa is adjacent to Esie where a group of similar steatite figures were found.

These Esie works conceivably also were identified with Moremi, the local heroine who became Ife’s queen.

A second copper alloy figure of a queen from the Ita Yemoo site is a tiny sculpture showing a recumbent crowned female circumscribing a vessel set atop a throne. She holds a scepter in one hand; the other grasps the throne’s curving handle (Fig.9). Her seat depicts a miniature of the quartz and granite stools identified in the modern era primarily with Ife’s autochthonous (Obatala-linked) priests. The scepter that she holds is similar to another work from Ita Yemoo depicting a man with unusual (for Ife) diagonal cheek mark (Willett 2004:M26a), a pattern similar to markings worn by northern Yoruba residents from Offa among other areas. The recumbent queen’s unusual composition appears to reference the transfer of power at Ife from the first dynasty rulership group to the new (second) dynasty line of kings, here symbolized through a queen, what appears to be

Queen Moremi, the wife of Obalufon II.

Another striking Ita Yemoo sculpture, a Janus staff mount shares similar symbolism. The work depicts two gagged human heads positioned back-to-back, one with vertical line facial marks, the other plain-faced, suggesting the union of two dynasties. This scepter likely was used as a club and

evokes both the punishment that befell supporters of either dynastic group committing serious crimes and the unity of the two factions in state rituals involving human offerings, among these coronations. This scepter mount’s weight and heightened arsenic content reinforces this identity. A larger Janus scepter mount from this same site depicts on one side a youthful head and on the other a very elderly man, consistent with two different dynasty portrayals, and the complementary royal unification/division themes.

A large Ife copper figure of a seated male was recovered at Tada (Fig. 11), an important Niger River crossing point situated some 200 km northeast of Ife. This sculpture is linked in important

ways not only to King Obalufon II, but also to Ife trade, regional economic vitality, and the key role of this ruler in promoting Ogboni (called Imole in Ife), the association dedicated to both autochthonous rights and trade. The work is stylistically very similar to the Obalufon mask (Fig. 1). Both are made of pure copper and were probably cast by members of the same workshop. Although the forearms and hands of the seated figure are now missing, enough remains to suggest that they may have been positioned in front of the body in a way resembling the well-known Ogboni association gestural motif of left hand fisted above right (Fig. 12). This same gesture is referenced in the smaller standing figure (also cast of pure copper) from this same Tada shrine (Fig. 13). Obalufon descendant Olojudo reaffirmed (p.c.) the gestural identity of the standing Tada figure. As I have argued elsewhere (1985) Yoruba works of copper are associated primarily with Ogboni and Obalufon, consistent with the latter ruler’s association with bronze casting and economic wellbeing.

Another notable Ogboni reference in these two copper works from Tada is the diamond-patterned wrapper (Morton Williams 1960:369, Aronson 1992) tied at the left hip with a knot. How the ancient Ife seated sculpture (and other works) found their way to this Tada shrine has been a subject of consider able scholarly debate. I concur with Thurstan Shaw in his view (1973:237) that these sculptures most likely were brought to this critical river-crossing point because of the site’s identity with Niger River trade. As Shaw notes (1973:237) these works seem to be linked to Yoruba commercial engagement along the Niger River “… marking perhaps important toll or control points of that trade.” Specifically, the seated Tada figure offers important evidence of Ife’s early control of this critical Niger River crossing point. Copper alloy castings of an elephant and two ostriches (animals identified with valuable regional trade goods) which were found on this same Tada site likely reference the importance of ivory and exotic feathers in the era’s long distance trade. The goddess Olokun (Fig. 14) who spans both the first and second dynasty religious pantheons, is closely identified with promoting related commerce.

Contesting Dynasties: Politics of the Body

Two copper alloy castings depicting royals (Figs. 15–16) offer important insight into early Ife society, politics, and history. One is the half-figure of a male from Ife’s Wunmonije site,

where a corpus of life-size copper alloy heads (Figs. 27–28) was unearthed. The other sculpture is the notably similar full-length standing figure from the Ife site of Ita Yemoo, the locale where

the royal couple (Fig. 8), tiny enthroned queen sculpture (Fig. 9), and metal scepter (Fig. 10) were created. Based on style and similarities in form, the two works clearly were fashioned around the

same time, conceivably during Obalufon II’s reign. Their crowns are different from the tall, conical, veiled are crowns worn by Ife monarchs today. The latter crown a form also seen on the tiny Ife

figure of a king found in Benin (Fig. 17).

Based on both their cap-form head coverings and the horn each holds in the left hand, the figures have been identified as portraying rulers in battle (Odewale p.c.). Not only are the rulers’ caps reminiscent of the smaller crowns (arinla) worn by Yoruba rulers in battle, suggests Odewale (p.c.), but historically, antelope horns similar to those carried in their left hands were used in battle. These horns were filled with powerful ase (authority/force/command), substances that could turn the course of war in one’s favor. When so filled, the horns assured that the king’s words would come to pass, a key attribute of Yoruba statecraft. The two appear to be competitors (e.g. competing lineages) vying for theIfe throne, references to the ruling heads of Ife’s first (Obatala) and

second (Odudua) dynasties shown here in ritual battle.

While these two royal sculptures are very similar in style and iconography, there are notable differences, including the treatment of the rulers’ faces—one showing vertical line marks, the

other lacking facial lines. There are also notable distinctions in headdress details, specifically the diadem shapes and cap tiers. The diadem of the Wunmojie king with striated facial marks (Fig. 15) displays a rosette pattern surmounted by a pointed plume, this motif resting atop a concentric circle. The headdress diadem on the plain-faced (unstriated) Ita Yemoo king figure instead consists of a simple concentric circle surmounted by a pointed plume. The rosette diadem of the king with facial striations seems to carry somewhat higher rank, for his diadem is set above the disk-form, as if to mark superior position. Moreover, the cap of the king with vertical facial markings integrates four

tiers of beads while the plain-faced king’s cap shows only three.

These differences both in crown diadem shapes and bead rows suggest that, among other things, the king bearing the vertical line facial marks and rosette-form diadem (the Wunmonije site ruler) carries a rank that is both different from and in some ways higher than that of the plain-faced royal.

There also are striking distinctions in facial marking and regalia details of these two king figures, differences that offer additional insight into the meaning and identity of these and other works from this center. Similar rosette and concentric circle diadem distinctions can be seen in many ancient Ife works. The Aroye vessel (Fig. 18), which displays rosette motifs and a monstrous human head referencing ancient Ife earth spirits (erunmole, imole; Odewale p.c.), may have functioned as a divination vessel linked to Obatala, a form today in Ife that employs a water-filled pot. The copper alloy head of first dynasty Ife goddess Olokun (Fig. 14) also incorporates a rosette with sixteen

petals. Ife chiefs and priests today sometimes wear beaded pendants (peke) that incorporate similar eight-petal flower forms or rosettes. These individuals include a range of primarily Obatala (first dynasty) affiliates: Obalale (the priest of Obatala), Obalase (the Oluorogbo priest), Obalara (the Obalufon priest), and Chief Woye Asire (the priest of Ife springs and markets. Rosette-form

diadems such as these also can be seen on ancient Ife terracotta animals identified with Obatala, among these the elephant (Fig. 20) and duiker antelope heads from the Lafogido site. These

rosettes suggest the importance of plants (flowers), and the primacy of ancient land ownership and gods to the Obatala group.

Concentric circle-form diadems, in contrast, seem to reference political agency as linked in part to the new Odudua dynasty (Akintitan p.c., Adelekan p.c.). In part for this reason, a concentric circle is incorporated into the iron gate at the front of the modern Ife palace. Agbaje-Williams notes (1991:11) that the burial spots of important chiefs sometimes are marked with stone circles as well. Concentric circle form diadems are displayed on the terracotta sculptures of ram and hippopotamus

heads from Ife’s Lafogido site. Both animals seem to be connected to the Odudua line and the associated sky deity pantheon of Sango among others (Idowu 1962:94, 142; Matory 1994:96).

If, as Ekpo Eyo suggests (1977:114; see also Eyo 1974) the group of Lafogido site animal sculptures were conceived as royal emblems, their distinctive crown diadems suggest that these

works, like the two king figures, were intended to represent two different dynasties and/or the gods associated with them. The king figure with vertical facial markings and a rosette-form diadem

instantiates the first dynasty or Obatala rulership line. The plain-faced ruler with concentric circle diadem evokes the second or Odudua royal line.

Number symbolism in diadem and other forms is important in these and other ancient Ife art works serving to mark grade and status. According to Ife Obatala Chief Adelekan (p.c), eightpetal rosettes are associated with higher Obatala grades. That the Wunmonije king figure wears an eight-petal rosette (Fig. 15) while the Aroye vessel (Fig. 18) and Olokun head (Fig. 14) incorporate sixteen-petal forms is based on power difference. Eight is the highest number accorded humans, suggests Chief Adelekan, whereas sixteen is used for gods.

Facial Marking Distinctions: Ife as a Cosmopolitan Center

One of the most striking differences in the two royal figures and other Ife arts can be seen in the variant facial markings. Scholars have put forward several explanations for these facial pattern disparities in Ife and early regional arts. Among the earliest were William Fagg and Frank Willett (1960:31), who identified vertical line facial marks with royal crown veils and the “shadows” cast onto the face by associated strings of beads. This is highly unlikely, however, since many ancient works depicting women and non-royals without crowns display the same vertical facial patterns. Moreover, of the two copper-alloy king figures (Figs. 15–16), only one shows vertical marks, and they both wear a kind of cap (oro) that does not include a beaded veil. Modern woodcarvings of Ife royals wearing traditional veiled crowns also do not show vertical line facial marks. Due to related inconsistencies, Willett would later retract his original shade-line theory and Fagg would not again discuss this in his later scholarship. As suggested above, the presence and lack of vertical facial marks on the two Ife king figures further reinforces the identity of these rulers as leaders of the two competing dynasties.

An array of early and later artistic evidence supports this. Among these is a Lower Niger style vessel (Fig. 21) collected near Benin that displays a human face with vertical markings beneath the head of an elephant, an animal that in Ife is closely identified with Obatala and the first dynasty. This elephant head has its complement in the Lafogido site terracotta elephant head with a rosette-form diadem (Fig. 20), a site where a terracotta head with vertical facial marks also was buried (Eyo 1974). Nineteenth and early twentieth century royal masks of the Igala (a Yorubalinked group) associated with the ancient Akpoto dynasty (who are ancestors of the current Igala rulers), display similar thin vertical line facial markings referencing the early royals of this group (Sargent 1988:32; Boston 1968:172) (Fig. 22). The ancient Ife terracotta head that represents Obalufon I (Osangangan Obamakin, the father of Obalufon II) displays vertical marks (Fig. 23) consistent with the king’s first-dynasty associations. Vertical line facial marks such as these appear to reference Ife royals (as well as other elites) and ideas of autochthony more generally. The fact that some 50 percent of the ancient Ife terracotta heads and figures show vertical line facial markings suggests

how important this group still was in the early second dynasty era when these works were commissioned. The second largest grouping of Ife terracotta works—around 35 percent—show no

facial markings at all, in keeping with modern Ife traditions forbidding facial marking for members of Ife resident families.

Ife oral tradition maintains that facial marking practices were at one point outlawed. Accordingly, late nineteenth to early twentieth century art and cultural practices display a strong aversion to facial marks of any type. Most likely it was Ife King Obalufon II who helped promote this change after his return to power as part of his plan for a more lasting truce. This change, and the need sometimes to cover one’s historical family and dynastic identity for reasons of political expediency, is also suggested by two masks, one of terracotta and one of copper, both identified with Obaufon II. One of these (Fig. 1) is plain-faced and the other (Fig. 24) has prominent vertical markings. Consistent with Obalufon II’s role in bringing to Ife, and serving as a key early art patron, his association with masking forms that shield (cover) the identities of the once-competing Ife groups is

noteworthy. Like a majority of ancient Ife sculptures with and without facial marks, these works appear to date to the same period, underscoring the fact that different groups were living together at Ife at this time.

Like the Wunmonije king figure (Fig. 15), the bronze head associated with the goddess Olokun (Fig. 14) also has vertical facial marks and a rosette-decorated crown. Olokun, the ancient Ife finance minister and later commerce, bead, and sea god, is said to date to Ife’s first dynasty. The copper alloy head now in the British Museum, with both vertical facial marks and a concentric circle diadem, appears to reference a chief in one of Ife’s autochthonous lineages (e.g. a number of first dynasty elite) who lived in Ife in the early second dynasty era before the ban on facial marking took effect.

Several Ife heads show thick vertical facial lines. These marks seem to depict individuals participating in rituals in which blister beetles or leaves (from the bùjé plant) were employed to mark the face with short-term patterns on the skin (Willett 1967:Fig. 23). These temporary “marks” may have served as references to first dynasty elites or their descendants during certain Ife rituals

(Owomoyela n.d. n.p.; Willett 1967:Figs. 13–14, pl. 23; see also discussion in Fagg and Willett 1960:31, Drewal 1989:238–39 n. 65). Interestingly, sculptures depicting these thick lines characteristically show flared nostrils and furled brows, suggesting the pain that accompanied facial blistering practices such as these. Several Florescence Era Ife terracotta heads (roughly 5 percent of the whole) display three elliptical “cat whisker” facial marks at the corners of the mouth (Fig. 25) similar to those associated with more recent northeastern Yagba Yoruba, a group who later came under Nupe rule.17 In one such sculpture, the marks extend into the cheeks in a manner consistent with later Yoruba abaja facial markings, indicating an historic connection between the two. According to Andrew Apter (p.c.), a group of Yagba Yoruba occupy an Ife ward where the Iyagba dialect is still sometimes spoken. Most historic Yagba communities are found in the Ekiti Yoruba region where early iron working sites have been found (Obayemi 1992:73, 74).19 It is possible that Ife’s Yagba population was involved in complementary iron-working and smelting activities at this center. This tradition also offers interesting insight into Benin figures holding blacksmith tools with three similar facial marks, works said to depict messengers from Ife.

A rather unusual Janus figure from ancient Ife shows a man with diagonal facial markings similar to those of historic and modern Igbo Nri titleholders, suggesting the role a similar group may have played in early Ife as well. Today it is Chief Obawinrin, head of Ife’s Iwinrin lineage, who represents Ife’s historic Igbo population during the annual Ife Edi festival. Associated rites are in part dedicated to Obalufon II’s wife, Queen Moremi, who is credited with stopping local Igbo (Ugbo) groups attacking Ife in the era in which she lived. Today Igbo residents also live in nearby regions south of Ife, among these communities such as Ijale (Abimbola p.c., Lawal p.c., Awolalu 1979:26).21 These Ife area Igbo populations appear to be distant relatives of autochthonous Igbo families, many of whom were forced out of the city by members of the new Odudua dynasty. Sculptures from Ife’s Iwinrin Grove, an Ife site closely linked to Ife’s “Igbo” population,

characteristically show vertical line facial markings consistent with works linked to first dynasty Ife history and autochthony. Another 5 percent of Ife sculptures portray Edo (Benin) style facial marks (forehead keloids) or patterns today characteristic of northeastern Yoruba/Nupe communities (a diagonal cheek line and/or vertical forehead line). The remaining 5 percent of the extant Ife terracotta works show unusual “mixed” facial patterns (generally “cat whisker” motifs along with other forms). These marks may reference intermarriages (social or political) at Ife in the early years of the new dynasty. The notable variety of these facial patterns in ancient Ife art makes clear the center’s importance as a cosmopolitan city sought out by people arriving from various regional centers. Features of Ife cosmopolitanism revealed in part through these variant facial markings are consistent with Ife’s identity as a center of manufacturing and trade. Similar issues are raised in Ife origin myths that identify this city as the home (birthplace) of humans of multiple races and ethnicities.

A Corpus of Remarkable Copper Heads Personifying Local Ife Chiefs

A striking group of life-size copper and copper alloy heads (Figs. 27–28) was unearthed in the 1930s at the Wunmonije site behind the Ife palace along with the above-discussed king figure

(Fig. 15).23 In addition to the original corpus of fifteen life-size heads from this site, a clearly related 4.25 inch high fragment of a copper alloy head consisting of a portion of a face showing a

nose and part of a mouth also was collected at an estate in Ado-Ekiti and has been described as “identical with those from Wunmonije” (Werner and Willett 1975: facing p. 142).

These sixteen life-size heads appear to have been created as part of the truce that Obalufon II established between the embattled Ife residents. One of the heads (Fig. 27) indeed is so similar to the Obalufon mask as to depict the same individual. Frank Willett, who published photographs of many of the life-size metal heads in his monograph on Ife, suggests (1967:26–28) that these works

had important royal mortuary functions in which each was displayed with a crown and robes of office, in the course of ceremonies following each ruler’s death. Willett proposes further that

the heads were commissioned as memorial sculptures (ako) consistent with a later era Ife and Yoruba tradition of carved wooden ako effigy figures used in commemorating deceased hunters. This theory, which identifies the corpus of life-size cast heads as effigies of successive rulers of the Ife city state, however, is premised on an idea (now largely discredited; see also Lawal 2005:503ff.) that the works were made by artists over a several-hundred-year period (the reigns of sixteen monarchs). This theory is problematic not only because the styles and material features of the heads are consistent, but also because the heads were found together (divided into two groups) and share a remarkably similar condition apart from blows that some of them received during their discovery. The shared condition indicates that they were interred for a similar length of time and under similar circumstances.

The formal similarities in these heads have led most scholars, myself included (Blier 1985), to argue that the works were created in a short period of time and by fewer than a handful of artists. With respect to style, as Thurstan Shaw notes (1978:134), “…they are of a piece and look like the work of one generation, even perhaps a single great artist.” These heads, I posited in this same article, were cast in part to serve as sacred crown supports and used during coronation rituals for a group of powerful Ife chiefs who head the various core first and second dynasty lineages in the city. These rites appear also to have been associated with Obalufon since related priests have a role in Ife coronations still today. The site where the heads were found today is identified as Obalufon

II’s burial site (Eyo 1976:n.p.). Ife Chief Obalara (Obalufon II’s descendant and priest) crowns each new monarch at a Obalufon shrine (Igbo Obalara) near the Obatala temple a short distance

from here (Verger 1957:439, Fabunmi 1969:10, Eluyemi 1977:41). Today, when a descendant of King Obalufon wishes to commission shrine arts in conjunction with his worship, two copper alloy

heads, one plain faced, the other with vertical line facial markings, are created (Oluyemi p.c.) (Fig. 30). Some of these ancient Ife life-size heads have plain faces. Others show vertical lines. These facial marking variables support the likely use of these heads in coronations and other rites associated with the powerful early Ife first- and second-dynasty-linked chiefs who were brought together as part of Obalufon II’s truce. The grouping of these heads, which in many ways also resemble the Obalufon mask (Fig. 1), together reference (and honor) the leaders of key families (now seen as orisa or gods) who had participated in this conflict. Obalufon II also created a new city plan as part of this truce, one in which the homesteads of these lineage leaders were relocated to sites circumscribing the center of Ife and its palace (Blier 2012). In the eighteenth–nineteenth centuries, when the city came under attack, the heads appear to have been buried for safe keeping near their original shrine locale after many centuries of use and their location eventually forgotten.

There are several ways that the heads could have been displayed in early Ife ritual contexts, among these earthen stepform altars and tall supports similar to one photographed with heads in Benin in the late nineteenth century (Fig. 29). The latter staff would account for the presence of holes near the bases of these works. Wooden mounts such as those known today here as ako were fashioned to commemorate Ife elephant hunters. These also could have been used for display purposes. A perhaps related Ijebu-Ode known as okute and discussed by Ogunba (1964:251) features roughly 4-foot wooden staffs with a symbolic human head. These pole-like forms were secured in the ground and “dressed” during annual rites commemorating early (first dynasty) rulers of the region.

A striking terracotta vessel (Fig. 30) buried at the center of an elaborate potsherd pavement at Obalara’s Land, an Ife site long affiliated with the Obalufon family, also offers clues important

to early display contexts of these heads. This vessel incorporates the depiction of a shrine featuring a naturalistic head with vertical line striations flanked by two cone-shaped motifs described by Garlake (1974:145) as crowns. The scene seems to portray an Obalufon altar with different types of crowns and a an array of Obalufon and Ogboni ritual symbols that find use in coronations,

among these edan Ogboni, consistent with the use of the Ife life-size heads in chiefly and royal enthronements overseen by the center’s Obalufon priesthood.

In a community outside of Ife, I learned of an important tradition that offers additional insight into this corpus of ancient Ife life size heads. In the local Obalufon shrine are found sixteen copper

alloy heads. While I was unable to see these works, in the course of several interviews with the elderly temple chief, I learned a considerable amount about them. He described them as erunmole

(imole, earth spirits).28 This identity underscores the likely association of the heads as sacred icons honoring ongoing offices and/ or titles (Abiodun 1974:138) rather than simple portraits (i.e. references to a specific person) (Underwood 1967:nos. 9, 11, 12). Consistent with this, each of the sixteen copper alloy heads located in this rural Obalufon temple is said by the priest to have been identified with a “powerful” individual from Ife’s distant past who was subsequently deified, among these Oramfe (the thunder god), Obatala (god of the autochthonous residents), Oluorogbo (the early messenger deity), Obalufon (King Obalufon II), Oranmiyan (Obalufon’s adversary, the military conqueror), Obameri (an ancient warrior associated with both dynasties), and Ore (the autochthonous Ife hunter). These names harken back to important early personages and gods in

the era of Obalufon II and the Ife civil war when the Ife life-size metal heads were made. The descendants and priests of these ancient heroes still play a role in the ritual life of this center. As

explained to me by the priest of this temple: “These imole are sixteen in number, all sixteen heads are kings [Oba, here meaning also deified chiefs], the sixteen kings of erunmole.” The Ogboni

association, of which this rural priest also was a member, similarly comprise here sixteen core members (titled officers). Lisa Aronson (1992:57) notes for the Yoruba center of Ijebu-Odu

that nearly 90 percent of the chiefs in this center are members of Ogboni. There are other connections between the tradition of Obalufon metal heads honoring historic leaders and Ogboni

arts. Not only are a majority of modern Yoruba copper alloy sculptures identified with both Ogboni and Obalufon, but the “sticks” (staffs) said to be secured to the modern Obalufon heads during display (Oluyemi p.c.), a ritual and aesthetic continuum extending back to the ancient Ife Florescence Era.

*As with the two Ife king figures (Figs. 15–16), differences in the ancient Ife life-size heads’ facial markings and other features offer additional insight to their identity and meaning. Half of these sixteen life-size metal heads display vertical line marks that I have identified with autochthonous (first dynasty) elites; the others have plain faces complementing the new dynasty’s denunciation of facial marking. As explained to me by the priest at the rural Obalufon temple where the grouping of copper alloy heads were housed: “there were sixteen crowns in the olden days, eight tribal and eight nontribal.” In using the term “tribal” here, he is referring to Ife’s autochthonous residents. Like the new city plan created by Obalufon II as part of his truce, these heads give primacy to the display and sharing of power by lineage heads of both dynasties.

Other features of these works also are important. A majority of the plain-faced heads, but not the striated ones, include holes around the beard line probably for the attachment of an artificial beard of beads or hair. In the twentieth century, beards in Yoruba art often identify important leaders, priests, and others by signaling senior age status and rank.30 Because all the plain-faced heads include beard holes, but only a few with facial markings do, the plain-faced works seem to be linked to power and/or status different than that of the heads with vertical facial lines. The non-bearded heads conceivably reference ritual status and sacral power consistent with Obatala lineages today; the bearded heads instead seem to convey ideas of lineage leadership and political status consistent with the center’s new rulership line.

Interestingly, four of the eight heads with facial lines are—like the Obalufon mask (Fig. 1) and the two of the Tada figures (Figs.11, 13)—cast of nearly pure copper (96.8–99.7 percent), a feat that

artists of ancient Greece and Rome, the Italian Renaissance, and Chinese bronze casters never achieved. The pure copper heads in this way differ materially from the stylistically similar heads that incorporate sizable amounts of alloys along with the copper (the associated copper content ranging from 68.8–79.8percent). A majority of the latter are without vertical facial lines. The five

nearly-pure copper heads additionally contain no detected zinc, a mineral that in the copper alloy heads ranges from 9.3–13.9 percent. Since half of the nearly- pure copper striated heads (two of the four) have beard holes, this small subset of works may have been intentionally differentiated in order to identify chiefs of both sacred and political status. One of these pure copper heads additionally displays red and black lines around the eyes (Fig. 28). This feature is said by Adedinni (p.c.) to identify a “most powerful person,” someone who is also a powerful imole (sacral power). To Obatala diviner Akintitan (p.c.), these eye surrounding lines reference someone who “can really see,” i.e., a person with unique access to the supernatural power that imbues one with spiritually charged insight.

Metal differences in these heads also carry important color differences that were significant to the ancient Ife patrons and artists. The pure copper works would have been redder, while those made from copper alloys were more yellow. The redder, nearly pure copper heads may have been linked to ideas of heightened potency or danger. And since casting pure copper is technically far more difficult than casting copper with alloy mixtures, the former heads also display greater skill, challenge, and risk on the part of the artist, attributes no doubt important to the meanings of these heads as well. This material feature, in short, also gives them special iconic power. The use of nearly pure copper in these works suggests not only how knowledgeable Ife artists were in the materials and technologies of casting, but also how willing they were to take related risks to achieve specific visual and symbolic ends in these works.

Dating Ancient Ife Art

How do the diverse forms and meanings of Ife’s early arts inform dating and other related questions? Dating ancient Ife art has posed many challenges to scholars, largely because many

of these artifacts come from secondary sites, rather than from contexts that can be dated scientifically to the period when the works were made and first used (e.g. primary sites). While developing a chronology of Ife art has proven difficult, several schema have been published in recent decades. Following the late Eko Eyo, some Ife scholars have utilized the term “Pavement Era” (and concomitantly “Pre-Pavement” and “Post-Pavement” periods) to distinguish those art works that are linked to the period of Ife’s famous potsherd pavements. However, because these

pavements are still seen (and used) in abundance in the center today, and in some cases reveal several different construction periods, the term “Pavement Era” is problematic. Ife historian

Akinjogbin instead takes up (1992:96) local temporal terms to discuss Ife chronology. Without attributing dates, he notes that one such local term, Osangangan Obamakin, in some situations