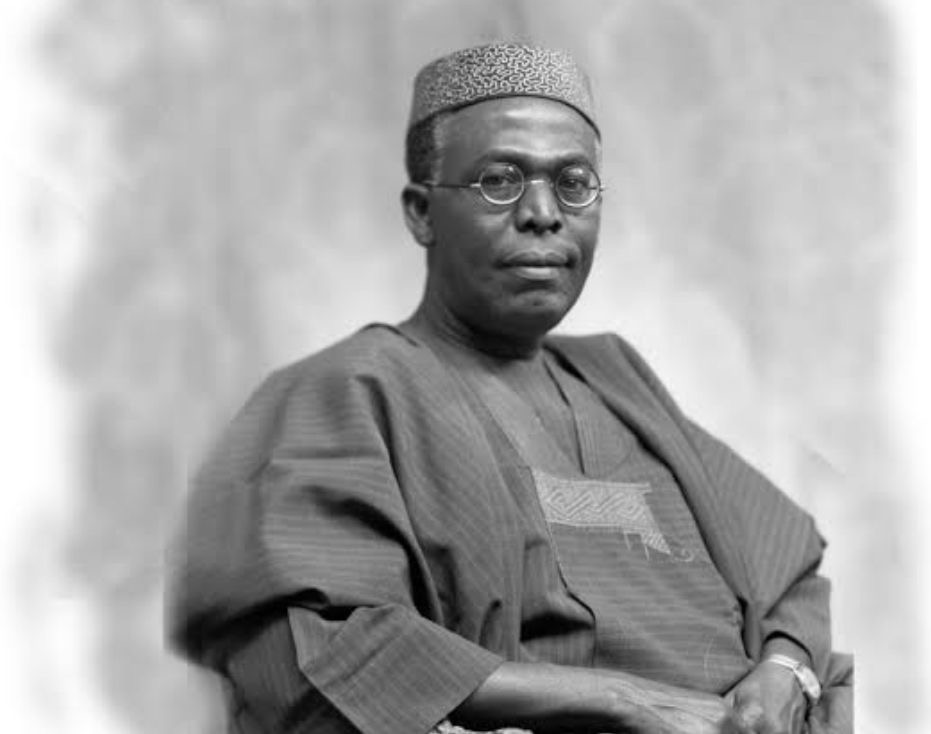

In the annals of postcolonial Nigeria, few figures have cast a shadow as enduring, as controversial, and as divisive as Chief Obafemi Awolowo. Hailed in some quarters as a visionary and nation-builder, he is equally condemned in others as a master of Machiavellian subterfuge whose thirst for power unraveled the sociopolitical architecture of the Yoruba people and set the Western Region on a path of destructive infighting, cultural inversion, and monarchical desecration. While his intellect was undoubted and his charisma undeniable, it is within the crucible of his political decisions that the most searing questions emerge—questions of loyalty, identity, ambition, and the calculated dismantling of indigenous authority.

In the annals of postcolonial Nigeria, few figures have cast a shadow as enduring, as controversial, and as divisive as Chief Obafemi Awolowo. Hailed in some quarters as a visionary and nation-builder, he is equally condemned in others as a master of Machiavellian subterfuge whose thirst for power unraveled the sociopolitical architecture of the Yoruba people and set the Western Region on a path of destructive infighting, cultural inversion, and monarchical desecration. While his intellect was undoubted and his charisma undeniable, it is within the crucible of his political decisions that the most searing questions emerge—questions of loyalty, identity, ambition, and the calculated dismantling of indigenous authority.

In this deeply researched exploration, we journey beyond the sanitized hagiography of textbooks and state propaganda to confront the less-spoken truths: how Chief Awolowo, a man of remarkable cognitive sophistication and legal acumen, unleashed a series of political decisions that not only fractured Yoruba unity but desecrated the symbolic and institutional throne of Oduduwa’s descendants. His political trajectory, marked by ideological rigidity, sectional loyalty, and internecine sabotage, deserves more than a romanticized appraisal; it demands a reckoning.

The tale begins not with Awolowo’s rise, but with the Western Region’s regal harmony—a symphony of crowns, palaces, and ancestral thrones that governed the Yoruba people through centuries of diplomacy, warfare, and sacred traditionalism. The Alaafin of Oyo, direct custodian of the imperial legacy of the Oyo Empire, stood as the apex of Yoruba political authority, while the Ooni of Ife retained the revered status of spiritual preeminence. This delicate duality—a balance between throne and shrine—had survived centuries of change, until it came under existential threat from the very hands meant to protect it.

Chief Awolowo’s entry into the political theatre brought with it not only a new lexicon of legalism and modern statecraft, but a deep-seated hostility towards certain traditional structures he saw as impediments to his vision of regional unity and central command. Behind his modernist rhetoric was a latent ambition to neutralize the influence of autonomous power centers—especially monarchs whose lineage and authority rivaled that of any elected officeholder. To Awolowo, the Alaafin represented a bastion of resistance too steeped in ancestral pride, too unyielding in tradition, too emblematic of a Yoruba aristocracy that refused to bow before party politics.

It was this ideological conflict that would crystallize into a political vendetta. The removal of Alaafin Adeyemi I—Omo Oba Lamidi Adeyemi’s father—was not merely a constitutional affair; it was a symbolic decapitation. Awolowo’s government, under the veneer of constitutionalism, orchestrated a campaign to dethrone Adeyemi I and send him into political oblivion. What offense had the monarch committed? He dared to preserve the dignity of his stool in an era where politicians demanded total allegiance. He resisted encroachment. He maintained the ancestral independence of Oyo in the face of a surging political machine.

Yet Awolowo’s machinations did not stop at dethronement. There were whispers—documented and oral—of plans to imprison the Alaafin at Kirikiri, a move that would have been an unpardonable desecration of Yoruba sacredness. The idea of confining an Oba—a custodian of centuries of wisdom and ritual—in a colonial jail built to house criminals, was not only an affront to Yoruba cosmology, but a loud declaration of war against a cultural institution that predates the Nigerian state itself.

This attack on monarchical dignity was part of a broader pattern. Awolowo’s falling out with Premier Ladoke Akintola, his former deputy turned adversary, mirrored his intolerance for political deviation. The Action Group, once a symbol of Yoruba unity and progressivism, became a battlefield of egos and ideological extremism. Awolowo’s obsession with command led to an intra-party purging, culminating in the infamous Western Region crisis—a descent into chaos that birthed the term “wild, wild west.” Streets were stained with blood, thrones desecrated, and palaces engulfed in the flames of political war. Awolowo, holed up in Ibadan, would rather see the region burn than concede space to any dissenting voice.

And herein lies the central paradox: How could a man so gifted in intellect, so passionate about federalism and education, descend into the politics of vengeance and cultural subversion? How could the supposed avatar of Yoruba progress be the same force that displaced its ancient institutions and insulted its regal memory?

The answer lies in his ideological construction—a dangerous cocktail of Fabian socialism, legal absolutism, and sectional ambition. Awolowo’s vision of governance, though draped in the regalia of modernism, bore the teeth of autocracy. His disdain for compromise, his refusal to entertain political plurality within his fold, and his vendetta against perceived rivals all suggest a mind too rigid for the demands of a pluralistic society. This rigidity explains why, despite his oratory brilliance and unmatched organizational skill, he never ascended the presidency of Nigeria. He was perceived, rightly or wrongly, as too sectarian—his politics too Western, his loyalty too tribal, his vision too narrow for a diverse federation.

Even among the Yoruba he professed to serve, questions lingered. Why was Ooni Adesoji Aderemi—an Oba of Ife whose spiritual authority was never meant to translate into political supremacy—elevated to the status of Governor-General of the Western Region? Why was Ife, a sacred city of origin and ritual, made the political darling, while Oyo—the imperial bastion of Yoruba political identity—was humiliated? Was this not a deliberate act to reconfigure the axis of power in Yoruba land, away from its traditional seat to a more pliable figurehead?

It is here that one must consider the Machiavellian genius of Awolowo. He understood, more than most, that to control a people, you must control their symbols. By elevating the Ooni, he created a counterweight to the Alaafin’s resistance. By politicizing the throne of Ife, he secularized a sacred stool and weaponized it in service of his political ambitions. What was once a dichotomy of reverence and governance became an arena of manipulation.

Yet in the end, his grand project collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions. By alienating traditional institutions, antagonizing political allies, and running a campaign of sectional absolutism, he not only destroyed the moral credibility of his movement but also became a prisoner of his own myth. Awolowo died with brilliance in his skull but failure in his hands—a man who built free education and courts of law but tore down palaces and sowed discord among his own kinsmen. His political tomb is lined with unfulfilled potential, broken oaths, and a trail of kings humiliated in the name of progress.

The legacy of Chief Obafemi Awolowo demands a reckoning—not through blind reverence or perfunctory national holidays, but through honest interrogation. Can a man be great if his greatness requires the suppression of others? Can a sage truly lead if his wisdom never matured into empathy? And can Nigeria ever evolve if it continues to idolize those who broke her soul while claiming to save her body?

This article shall continue, unveiling further how the seeds of today’s Yoruba political fragmentation were sown in those tragic decisions of yesteryear—when ambition disguised as vision, and genius misapplied as domination, brought a region of crowns to its knees.

By : Jide Adesina

1stafrika.com

All rights reserved

@2025