In the dark cell of Nigeria’s brutal war-torn years, when silence was mistaken for loyalty and dissent branded as treason, one man stood between the crushing weight of tyranny and the flickering flame of the human conscience. The Man Died, Wole Soyinka’s searing prison memoir, is more than a record of incarceration—it is a bold declaration of intellectual resistance, an elegy of conscience, and a timeless call to speak, to write, and to stand when all else collapses into fear. It is not merely a book. It is a cry from the deep, the soul-scrawl of a mind denied its freedom yet never broken.

In the dark cell of Nigeria’s brutal war-torn years, when silence was mistaken for loyalty and dissent branded as treason, one man stood between the crushing weight of tyranny and the flickering flame of the human conscience. The Man Died, Wole Soyinka’s searing prison memoir, is more than a record of incarceration—it is a bold declaration of intellectual resistance, an elegy of conscience, and a timeless call to speak, to write, and to stand when all else collapses into fear. It is not merely a book. It is a cry from the deep, the soul-scrawl of a mind denied its freedom yet never broken.

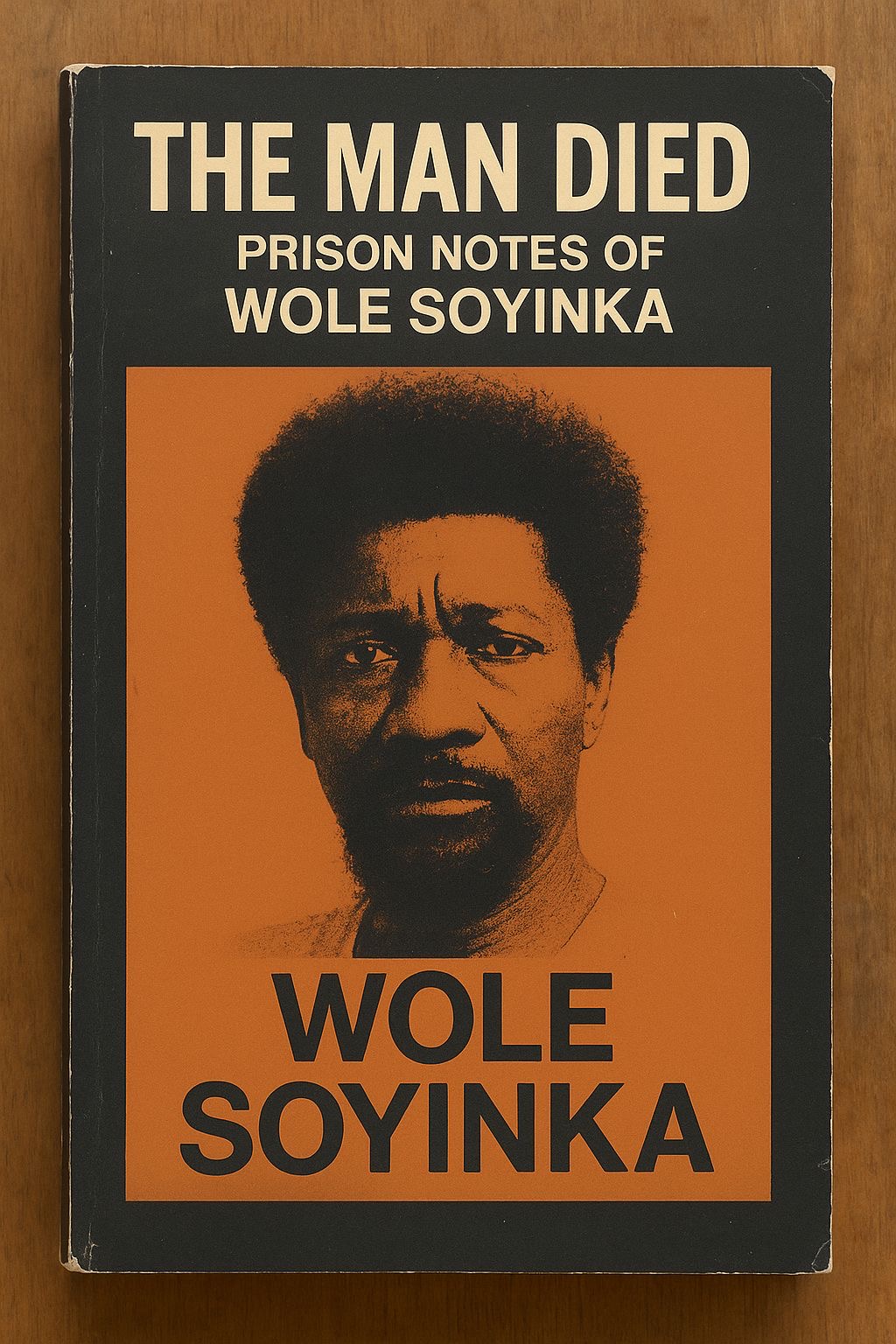

Wole Soyinka, playwright, poet, and moral lighthouse of his generation, was thrown into solitary confinement in 1967 at the height of the Nigerian Civil War. His crime was not violence. It was his refusal to be silent. As Nigeria bled, torn apart by the Biafran secession, Soyinka sought peace—not through arms, but through dialogue. He traveled discreetly, attempting to open lines of communication between both sides, believing in the possibility of a nation preserved by mutual understanding. But in a time when even the whisper of peace could be heard as betrayal, his quiet efforts were deemed dangerous. The military regime of General Yakubu Gowon ordered his arrest. He was detained for nearly two years—without trial, without charge, and most tellingly, without light.

What followed was not merely incarceration but an assault on the spirit. In the barren belly of the prison system, Soyinka endured what few could survive: 22 months of near-total isolation, sensory deprivation, malnutrition, and deliberate cruelty. The walls were narrow, the air thick with neglect, and time stretched like an endless wound. Yet, within this darkness, he wrote—on toilet paper, cigarette packs, even his own mind when pen and paper were denied. What he wrote became The Man Died, a title that emerges not just from observation but from the innermost reckoning of moral decay. For, as he famously inscribed, “The man dies in all who keep silent in the face of tyranny.”

This book is not a chronological diary. It is a pulsating, fragmented mosaic of thought and resistance. It veers between the poetic and the polemical, the personal and the political, the surreal and the scholarly. Soyinka’s voice traverses dreams and nightmares, interrogations and memories, philosophy and fury. His prose is fiercely lyrical, filled with metaphors that burn slowly like lit coals beneath frost. He invokes Orwell, Plato, Nietzsche, and Yoruba cosmology, weaving a tapestry of defiance that is both African and universal.

What makes The Man Died extraordinary is not just what it describes but what it evokes—the soul-warping effects of state brutality, the terrifying silence of a nation too afraid to speak, and the inner war of a man determined not to lose his mind or humanity. This is not just a Nigerian story. It is a global parable of all men and women imprisoned for their voice, from Nelson Mandela’s Robben Island to Solzhenitsyn’s gulags, from Ken Saro-Wiwa’s gallows to the silent exiles of our digital age.

Soyinka does not spare his country. He does not disguise his disappointment. In razor-sharp passages, he calls out not only the military elite who weaponized fear but also the so-called intellectuals and artists who abandoned their duty to truth. For Soyinka, complicity is the great unspoken evil. He understands that dictatorship thrives not only on guns but on the absence of moral courage in everyday men.

And yet, The Man Died is not without moments of transcendent beauty. Amid the desolation, Soyinka finds sparks—birds at the prison window, memories of friends, flashes of laughter, even hallucinated conversations with the dead. These fragments become lifelines. They remind him—and us—that the human spirit, even bruised and bludgeoned, is luminous when lit by conviction.

This memoir was not written for pity. It is a challenge. A document of indictment, yes, but also of invitation—an invitation to think, to speak, and above all, to remember. For in forgetting lies the quiet burial of freedom. Soyinka does not want us merely to know what happened. He wants us to feel it, to be disturbed by it, to interrogate our own silences in the face of injustice.

As the pages unfold, you begin to hear the heartbeat of a man who, though caged, remained free. A man who turned suffering into testimony, isolation into reflection, pain into literary fire. When Soyinka writes, “Justice is the first condition of humanity,” he is not offering a slogan. He is offering the very foundation upon which a meaningful life—and society—must be built.

The Man Died remains, more than fifty years after its first publication, a towering work of protest literature. It is a sacred scroll for freedom fighters, writers, and thinkers across continents. It belongs on the same shelf as Letters from Birmingham Jail, Night by Elie Wiesel, and Conversations with Myself by Mandela. It is at once a Nigerian tragedy and a universal warning.

In an age where silence has become a survival tactic and truth is bent by convenience, Soyinka’s voice calls through time like a trumpet in the wilderness: Do not die while you yet breathe. Do not let fear bury your humanity. Do not remain silent when the world needs your voice.

Conclusion:

The Man Died is not just Wole Soyinka’s story. It is a collective memory. It is the portrait of a society on the brink, painted by the last man standing when all others looked away. It is literature born of pain and purpose. It is the ink of resistance. And long after the bars rust, the guards vanish, and the prison walls fall, his words remain—unyielding, urgent, and immortal.