“As Always…. a Painful Declaration

I have been happy

being me:

an African

a woman

and a writer.

Just take your racism

your sexism

your pragmatism

off me;

overt

covert or

internalized

And

damned you!”

“An Angry Letter in January” Ama Ata Aidoo.

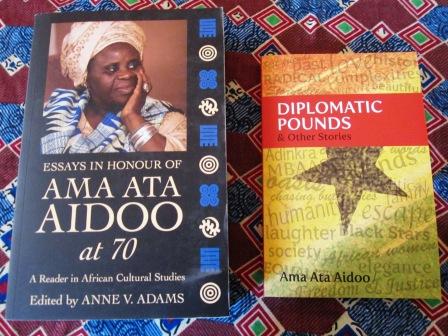

Professor Ama Ata Aidoo, née Christina Ama Aidoo is an internationally recognized literary

and intellectual Ghanaian figure of ethnic Fante extraction. She is as an accomplished author, poet, playwright, academic, feminist, and beacon to writers the world over. Aidoo is also a former Minister of Education in the Ghana government. Her novel ‘Changes: a Love Story” won the coveted Commonwealth Writers Prize for Best Book (Africa) in 1992. She is also an accomplished poet – her collection Someone Talking to Sometime won the Nelson Mandela Prize for Poetry in 1987 – and has written several children’s books.Aidoo is the editor of the anthology African Love Stories.

On Wednesday, September 17th 2014 at the British Council in Accra, Ghana, the much awaited documentary on Prof Aidoo entitled “The Art of Ama Ata Aidoo” put together by Yaba Badoe and Amina Mama, was finally premiered. The Art of Ama Ata Aidoo explores the artistic contribution of one of the Africa’s foremost woman writers, a trailblazer for an entire generation of exciting new talent. The film charts Ama Ata Aidoo’s creative journey in a life that spans 7 decades from colonial Ghana through the tumultuous era of independence to a more sober present day Africa where nurturing women’s creative talent remains as hard as ever.

Aidoo is an outspoken woman who, in the tradition of some of her predecessors such as Flora Nwapa (Nigeria) and Efua T Sutherland (Ghana) both resists and subverts traditional literary boundaries. Femi-Ojo (1982) pejoratively labelled her as belonging to the “old guard” of African women writers who are less ideologically aggressive, but Aidoo is nevertheless respected by well-established writers such as Buchi Emecheta -who thinks of herself as Aidoo’s new sister-or by the still-relatively unknown Ghanaian writer Ama Darko-who pays respects to Aidoo as her literary mother.

María Frías in her 1998 interview with Prof Aidoo entitled “An Interview with Ama Ata Aidoo: “I Learnt my First Feminist Lessons in Africa,” described her as “a medium-sized, strongly built, round-faced woman who wears Ghanaian dresses, and rich, colorful, and beautiful headwraps tied to her dignified head.” Frias further averred that Prof Aidoo`s celebration of the African story-telling tradition, her critical view of the Western world, her rebellion against “the colonization of the African minds”, and her preoccupation with the future of her country and her Ghanaian people-women in particular-makes a conversation with Ama Ata Aidoo a learning experience. Her voice always sounds fresh, critical, outrageous and full of life.

She has consistently and fascinatingly explored her society through many plays, novels, short stories and poems. Aidoo is the author of plays The Dilemma of a Ghost (1965), and Anowa (1970); short stories No Sweetness Here (1979), and The Girl Who Can and Other Stories (1999); novels Our Sister Killjoy or Reflections from a Black-Eyed Squint (1977), and Changes (1991); collections of poems Someone Talking to Sometime (1985), and An Angry Letter in January and Other Poems; children’s books The Eagle and Chickens and Other Stories (1986), and Birds and Other Poems (1987).

Her fictional works are explicitly critical of the colonial history of Ghana, and of what she refers to as the “dance of masquerades called independence”. Anowa (1970), No Sweetness Here (1970), Our Sister Killjoy (1977) describe and criticize oppression and inequality, target colonialism and implicitly deny the term “postcolonial”. Aidoo is also known as an important feminist writer. Her

works feature strong female protagonists who are faced with institutionalized and personal sexist attitudes on a daily basis. In her non-fictional writings, Aidoo also explicitly fights against the axis of oppressive social constructions of gender and their consequences for women. She blames colonialism for importing “a fully developed sexist system, which has been adapted, maintained and exacerbated as it has been integrated into different aspects of African culture” (Marangoly, Scott

1993: 299). As with other African women writers, to use Busia’s words (1989-90: 90), Aidoo challenges, deconstructs, and subverts the traditional “voicelessness of the black women trope”.

One how she became a successful writer, Amat Ata Aidoo wrote in “To Be a Woman” (1985: 259), with a quote from her uneducated aunt: “My child, get as far as you can into this education. Go until you yourself are tired. As for marriage, it is something a woman picks up along the way”.

Through her short story writing prowess as exhibited in “No Sweetness Here”, Ama Ata Aidoo caught the attention of the celebrated literary giants Langston Hughes, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka and others and was invited to the African Writers Workshop at the University of Ibadan in 1962 when she was only 22 years old. At these Workshop Ama Ata Aidoo did not only interacted with African literary giants and received exposure but she also met a very young ‘Molara Ogundipe Leslie who also a student and a participant at the workshop.

Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe and Ghanian writer Ama Ata Aidoo

Ama Ata Aidoo perceives herself as a teacher, first and foremost, and like to teach her students about other African women writers. “I have been teaching Mariama Bâ (So Long a Letter), Bessie Head (A Question of Power), Buchi Emecheta (Joys of Motherhood) -which is a must-and, although she is not by nationality an African, I’ve always taught Marise Condé (Segú). In drama, I wouldn’t even move one inch without teaching Efua Sutherland, especially ‘The Marriage of Anansewa.” I always teach Nawal El Saadawi and there are a whole lot of other women (Frias 1998: 18-19).

Though venerated in Europe and the USA as the foremost African feminist-a fact that she somewhat resents and long immersed in gender issues-both at a personal, political, and literary level- Aidoo still questions artificial critical constructions. Her women, though, following the principles of the Akan society she comes from, are strong, hard-working, independent, articulate, and smart, thus, deconstructing the stereotypical image of the submissive, passive, and battered African woman. Aidoo herself takes pains to explain the reasons for portraying these provocative female protagonists: People say to me: “Your women characters seem to be stronger than we are used to when thinking about African women”. As far as I am concerned these are the African women among whom I was brought up. In terms of women standing on their own feet, within or outside marriage, mostly from inside marriage, living life on their own terms. (Wilson-Tagoe, 200: 248).

Ama Ata Aidoo made her glorious debut into this theatre of life in 23 March 1940 at Saltpond in the Central Region of Ghana. She grew up in a Nkusukum (sub-ethnic Fante group) royal household as the beloved daughter of Nana Yaw Fama, chief of Abeadzi Kyiakor, and Maame Abasema. Her Fante (Akan) ethnic group are matriarchal people and openly favors women to the extent that the mother of four sons still considers herself “infertile” because she could not have any daughters, and where women are supposed to have the authority but not the power to rule-Aidoo’s (for some) progressive portrayal of African women is simply a reflection of what she saw: “I got this incredible

birds-eye view of what happens in that society and I definitely knew that being a woman is enormously important in Akan society” (Wilson-Tagoe, 2002: 48).

In tandem with Fantes favoritism for women, women education is not joked with with at all as Dr James Emman Kwegyir Aggrey, the famous African educator and an unadulterated Fante ssummed it up: “If you educate a man, you educate one person but if you educate a woman, you educate a whole nation.” even with this quote the original states “. . ., if you educate a woman, you educate a family”).

In line with the Fante tradition, young Nkusukum princess Ama Ata Aidoo had her basic education at Saltpond and afterwards, was sent by her father to Wesley Girls’ High School in Cape Coast from 1961 to 1964. The headmistress of Wesley Girls’ bought her her first typewriter. After leaving high school, she enrolled at the University of Ghana in Legon and received her Bachelor of Arts in English as well as writing her first play, The Dilemma of a Ghost, in 1964. The play was published by Longman the following year, making Aidoo the first published African woman dramatist.

She worked in the United States of America where she held a fellowship in creative writing at Stanford University. She also served as a research fellow at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, and as a Lecturer in English at the University of Cape Coast, eventually rising there to the position of Professor.

Aside from her literary career, Aidoo was appointed Minister of Education under the Provisional National Defence Council in 1982. She resigned after 18 months. She has also spent a great deal of time teaching and living abroad for months at a time. She has lived in America, Britain, Germany, and Zimbabwe. Aidoo taught various English courses at Hamilton College in Clinton, NY in the early to mid-1990s. She is currently a Visiting Professor in the Africana Studies Department at Brown University.

Ama Ata Aidoo sitting down with her colleague Kenyan writer Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, the famous author of Weep Not Child novel. Courtesy Nana Kofi Acquah.

Aidoo’s works of fiction particularly deal with the tension between Western and African world views. Her first novel,” Our Sister Killjoy”, was published in 1977 and remains one of her most popular works. In “Our Sister Killjoy”, Aidoo is concerned mostly with the estrangement of the African educated class. Sissy, the main character, is offered a grant to receive a European

education. Her journey into the west chronicles different aspects of her resistance to the overriding ideological hostilities that bring down Africa and African people.The novel is divided into four parts. “Into a Bad Dream” relates Sissie’s travel experience to Germany. She is secure in her racial background, and only progressively over the itineraries of her ‘westbound mobility’ does she

become conscious of her colour complexion. In “The Plums,” Sissie discovers Marija, a new German friend. Marija is entangled in boredom and immediately gets caught within the exotic Other ‘the black-eyed squint’ student stands for. In the course of their friendship, Sissie finds out Marija’s perverted behaviors, rejects her lesbianism and leaves her in frustration and total disillusionment. In “From Our Sister Killjoy,” Sissie moves to London, the colonial capital which brings back into her

mind the whole tale about the British colonial experience in Ghana. She appears to be extremely disappointed at the tragic social reality and marginalization of black African immigrants. In the epistolary section on a “Love Letter”, Sissie is engaged in a mock-conversation with a lover, using an extremely sarcastic style to assert her identity through the experiences she went through.

Raised in, respectful towards, and proud of her African oral tradition and the ancient story-telling, Aidoo’s forte is in her dialogues. Aidoo invests her female characters with the powerful tool of speech. Her African women make use of words as weapons to the extent that they can easily and intelligently fustigate men’s egos and beat them dialectically /metaphorically, at the same time gaining the respect of the other sisters in the community.

A farewell hug

Students and faculty colleagues bid farewell to Ghanaian playwright Ama Ata Aidoo. Credit: Mike Cohea/Brown University

Furthermore, in Allan’s words (1994: 188-89), Aidoo’s instinctive and innovative use of similes and proverbs is an effective rhetorical tool which shows women’s verbal dexterity at the same time as it highlights collective wisdom: Africanisms, new words coined from the alchemic blending of English and the African cultural scene, enrich Aidoo’s linguistic repertoire. Such terms as “flabberwhelmed”, “negatively eventful”, and “away matches” violate standard English in order to express a socio-linguistic identity that is uniquely African.

Aidoo has travelled widely, is not blind to the trauma and pain of the African diaspora, and has personally experienced the always confl ictive encounter between African and Western cultures. Maybe this is the reason why some of her female protagonists also undergo a physical and emotional journey that is painful and traumatic, though always instructive and regenerative. Aidoo deals with the impact of colonialism, postcolonialism, and neo-colonialism on the bodies and psyches of her African women characters but, contrary to the “nervous condition” of Dangarembga’s female protagonist, Aidoo’s women are much more in control of their bodies and minds and they can always come back home-though psychologically injured, physically exhausted, emotionally disillusioned, and culturally alienated-start a new life, or choose a liberating but tragic ending. Though confronted with and struggling against social norms and cultural disintegration as well as with the traumatic dichotomy of African tradition versus Western modernity, Aidoo’s women-albeit shaken-retain their sanity and are able to articulate their anger. Madness-a recurrent

theme in post-colonial African fiction Femi-Ojo (1979), Adepitan (1993/94)-does not hit /affect Aidoo’s heroines. Only in the case of Anowa did Aidoo contemplate the possibility of her protagonist ending up insane, but she thought it too cruel, and handed Anowa the privilege of choosing her own death. Aidoo’s women are peripatetic beings who cross boundaries-geographical, social, cultural, and emotional-who dare to step over patriarchal borderlines, who violate traditional discourses on the cult of marriage and motherhood, at the same time as they dramatize their vulnerability and their subjugation to African tradition. As Allan (1994: 178) argues, by portraying African women’s tensions, frustrations, and contradictions, Aidoo’s works refl ect on the dual theme of “social stasis”-tradition-versus “change”-modernity.

source:http://publicaciones.ua.es/filespubli/pdf/02144808RD16064646.pdf

“THE ART OF AMA ATA AIDOO” : A DOCUMENTARY by Yaba Badoe and Amina Mama

The art of Ama Ata Aidoo is a very thrilling exploration of the vast universe that is Ama Ata Aidoo’s mind and it’s phenomenal expression in her literary works which have so shaken up the very foundations of literature in Ghana and Africa.

Traversing her life from the inception of her art to its explosion, the documentary gives quite a vivid insight into the cultural, societal, and familial influences that, in many ways, were the inception of the great literary mind that was Ama Ata Aidoo’s.

Yaba Badoe (right) and Ama Ata Aidoo in conversation at the AWDF African Women in Film Forum

In the documentary, Ama Ata Aidoo remembers stories her mother used to tell her in the early mornings in the village (not the usual nighttime storytelling style), of a preacher-man/ evangelist who came by the village when she was young, of her royal birth and subsequent disregard for the institution of royalty.

In the nostalgia of black-and-white, sepia-tinted pictures, she also shares the fairly pivotal influence of a teacher in Wesley Girls High school who gave a young Ama Ata Aidoo her first typewriter after she expressed the ‘crazy’ desire to be a writer.

Her time in Takoradi was another pivotal moment in Ama’s life where she participated in a Christmas story competition running in the Daily Graphic at the time.

Her story was published, which turned out to be a milestone for her, being the very first of her work that got published. And she got paid!

With interviews of Prof. Carole Boyce Davies and Prof. Anne V. Adams from Cornell University, Prof Irwin Appel of the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Prof. Nana Wilson-Tagoe (University of Missouri), the documentary encouraged intense contemplation, as well as self-introspection, into the very controversial issues Ama Ata Aidoo was fearless to raise in her works.

She says quite bluntly of controversy, “How can you call yourself a writer, if you’re running away from controversial issues?” And so controversial issues there were:

The contemporary Ghanaian woman battling the stereotype. Talking about the character Esi in her novel Changes in the documentary, Ama Ata Aidoo shared the numerous accusations readers made of her, “She’s cold”, “She’s selfish”, “She’s not a good mother”, etc. and in her blunt and matter-of-fact way, Ama Ata Aidoo reminds all outraged sensibilities that this earth is not only for the warm, the unselfish, and good mothers.

Ama Ata Aidoo receiving award at the 5th anniversary of African Women Development Fund

The dark business of slavery and the guilt-driven Ghanaian treatment of a past they would rather not deal with. Yaba and Amina’s documentary explored Theatre in telling the story of Ama Ata Aidoo’s words and their universal truth. In deliberate juxtaposition, Yaba Badoe and Amina Mama show scenes from the performance of ‘Anowa at the University of California , Santa Babara, in conjunction with Ama Ata Aidoo reading the words of the play. I find what this did for me as a viewer was a play on the very different ways in which her Ama’s words could be interpreted in the different voices that were employed. Reading (and acting) a section of Anowa which recounted what her grandmother said to her about places she’d been to, Ama Ata Aidoo’s voice was motherly, and softly censorial, as is usual of a Ghanaian grandmother to her eager and curious grandchild. The African American actress, Erin Pettigrew, said those very same words with all the weight of a painful history of which she was a consequence of. Where ‘places’ was a thing of sad and painful wonder in an older Ama Ata Aidoo’s voice, ‘places’ in young Erin’s voice had a ring of desperation and an exuberant, tearful anger and indignation. Where Anowa would have been interpreted as a sad love story, excerpts from this play hinted a more heavy-handed focus on the issues of slavery which Ama Ata Aidoo raised in that timeless play. “Ghanaians have always been nervous of the presence of the Diaspora here,” Ama Ata Aidoo says.In interviews about the play included in the documentary, the many factors which might have influenced the mindscape of Ama Ata Aidoo as she wrote Anowa are examined: She being a Ghanaian writer in the United States of America in the ‘sixties, a time of the Black Civil Rights movements, a time of burgeoning feminism, the hippie revolution and so much more. All of this played a huge part in the themes and allegory probed into in Anowa.

African Writers lunch with Ama Ata Aidoo, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, Nii Ayi Parkes, Martin Egblewogbe, Nana Fredua Agyeman, Nana Nyarko Boateng, Nana Ayibea Clarke and Kinna Likimani.

Language. Speaking about the medium she writes in: English, Ama Ata Aidoo shared that since it was English she had chosen to write in, she would make sure all her characters were as authentically Ghanaian as possible which informs her very unique style of speech, using simple words in symbolic ways, very much like the proverbial speech of Ghanaian local languages.4. Her phenomenal work Our sister Killjoy and her hints on the topic of lesbianism in the piece. Ama Ata Aidoo shared how she was attacked from both sides; by Ghanaians who accused her of introducing something foreign to Ghana and lesbians who accused her of not thoroughly dealing with it because she disapproved.5. Her work as the Minister of Education, the unapologetic chauvinism of parliament and how it interfered with her writing. She spoke very candidly, as is her style, of how in Cabinet, when the men spoke, everyone treated it as important, but when she began to speak, “suddenly, those who were smokers would light a cigarette, others would suddenly want to pass notes” and such in the typical, chauvinistic manner with which most Ghanaian men treat women, leaders or not. Even worse, was how her work as a writer was interfered with due to her ministerial duties, to which the very wise Ama reflected, “Writers, just write. Everything else is secondary.”

The Woman’s story that is never told. “Women’s biographies and stories are not told, women do not take the attribution that they ought to take and this is why we ought to be proud of this documentary, in this most provocative medium,” Prof. Esi Sutherland said in her speech at the premiere of the documentary. And that was what we did last night, celebrate a phenomenal woman whose fearlessness and incredible gift has left a legacy that spans continents and cultures to become something universal.

My only qualm was that there was very little shown of the great impact of Ama Ata Aidoo on Ghanaian pupils and students.

I felt a holistic story of such a universal, and national, figure was not complete without this.

Though the scenes of Anowa, Dilemma of a Ghost, being treated in an American university was a powerful way of showing that the relevance of Ama Ata Aidoo’s work had gone beyond the Ghanaian shores, Ghanaian school children who read her work as prescribed literature, teachers of all levels who teach her work, were also scenes I felt needed to be included.

This would have added great perspective in telling about the national legend Ama Ata Aidoo is for us as Ghanaians.

On the whole however, the documentary is outstanding in portraying how Ama Ata Aidoo has become not just a Ghanaian song of celebration, but a timeless tune that is sung across continents and cultures, across races and differences, to become a cosmic figure, not just in Ghanaian, African or African American literature, but Literature as a whole.

By: Nana Akosua Hanson/citifmonline.com/Ghana