The Kafkaesque existence that millions of people suffered through under South Africa’s apartheid laws is rendered with powerful simplicity in “Sizwe Banzi Is Dead.”

Currently presented by the McCarter Theater Center in Princeton, this production arrives from the Market Theater of Johannesburg and has been directed by John Kani, who wrote the play with Winston Ntshona and Athol Fugard in 1972.

When the two-actor drama was staged on Broadway in 1974 (in repertory with “The Island,” another work created by the trio) with Mr. Kani and Mr. Ntshona as its interpreters, they shared an unusual joint Tony Award for best performance by a leading actor. It is obvious that Mr. Kani understands well the nuances of staging and performing this remarkably subtle work.

What makes “Sizwe Banzi Is Dead” such persuasive theater is the way it evokes a nightmarish world using understated means. There is no screaming, gunfire or impassioned invective. Instead, the 90-minute drama translates the repressive horror of apartheid into human terms through the use of easygoing humor in its early passages, then shifts into graver tones as the play progresses.

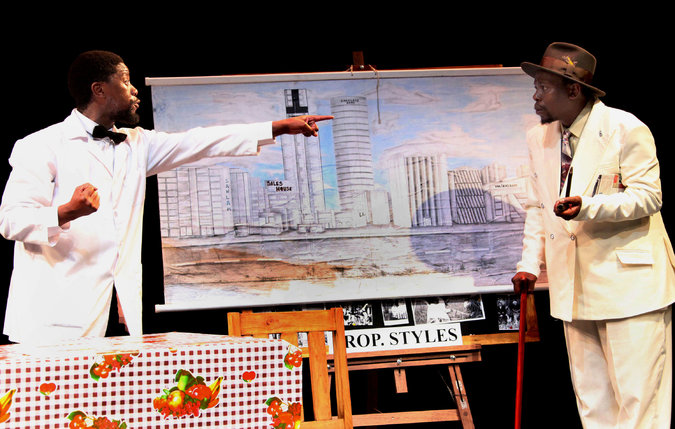

Starkly set against a black background are two tables, a chair, a camera on a tripod and a display board of photographs that suggest a modest photography studio. It is owned by Styles, a cheerful young man, and situated in a black township located outside Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Wearing a bow tie and a white dustcoat, Styles is first discovered chuckling over a newspaper.

Speaking directly to the audience, Styles tells an amusing anecdote about his previous job as a worker at a disorderly Ford Motor Company factory, which convinced him to become his own boss and turn his hobby into a profession. Styles disarmingly chats about the ways his photos help record the dreams and achievements of “simple people.”

A prospective customer enters. A stocky, shy fellow resplendent in a new suit, he eventually poses for several portraits. As a final camera flash goes off, he briefly freezes, smiling, as the studio disappears into darkness. The photograph then comes to life, and the man is heard dictating the letter to his wife that will accompany the portrait.

“I’ve got wonderful news for you,” he says. “Sizwe Banzi, in a manner of speaking, is dead!”

This man — the customer from the photo studio — is none other than Banzi himself, and the remainder of the play, which is set in the early 1970s, relates in an extended flashback the way he reluctantly came to assume the identity of another individual in order to get on with his life.

Crucial to the story is Banzi’s passbook, an official document that, under apartheid, all black South Africans were required to carry at all times. In addition to a photograph and other descriptive information, the passbook stipulated where the holder could live and work.

Banzi has strayed far from his home to seek employment near Port Elizabeth, and now finds himself trapped there beyond his permitted time limit. He could face fines and imprisonment. He cannot get a job or start a business, or venture into the streets for that matter, without showing that his passbook is in order. And Banzi’s document is certainly not in order.

Fortunately, a friend of a friend named Buntu and a chance occurrence combine to deliver Banzi from his predicament.

The play illustrates South Africa’s dystopian apartheid system by degrees, beginning with Styles’s personal history and bureaucratic struggle to open his own business. As Banzi’s passbook issues arise, a terrible picture of apartheid slowly comes into focus.

Staged with minimal scenery, Mr. Kani’s production is cunningly austere. His son, Atandwa Kani, neatly portrays both the upbeat Styles and the forthright Buntu. Mncedisi Shabangu appealingly depicts Banzi with a musical voice and a sweet smile. Their interaction is natural and confident.

The performances make this penetrating play all the more compelling.