Analysis: A combination therapy – helping the body’s own defences fight cancer cells – has shown impressive results for terminally ill melanoma patients

Immunotherapy is the most exciting development in cancer treatment in years, beginning to take off at a time when much cancer drug research seems to be hitting a brick wall. More and more of the orthodox chemotherapy drugs have very small effects, buying people with the advanced disease a few months or even just weeks of life, as the Guardian reported on Saturday.

But the scientists working on immunotherapy have set out in an entirely different direction, tricking the body’s own defences into fighting the enemy cancer within. For a long time, this has been an aspiration. The concept dates back to the 1970s and for decades the big pharmaceutical companies showed little interest. Other drugs looked like much more certain money-earners. But now there is real evidence that immunotherapy can sometimes halt terminal cancers in their tracks and big pharma is joining the bandwagon with a vengeance.

In Chicago, at the American Society for Clinical Oncology (Asco) annual meeting, where so many promising cancer drugs have been announced in the past – not always in the long term fulfilling the high hopes – experts are saying that the results of a trial involving a combination of two new immunotherapy drugs for melanoma (skin cancer) patients are spectacular.

Half the patients in the British trial, considered terminally ill and with little time left, responded to ipilimumab, a drug licensed four years ago, combined with the new and as-yet-unlicensed drug nivolumab. On its own, ipilimumab works for around a fifth of patients. The combination of the two shrank the tumours of 58% of patients. There is hope they may disappear altogether. Results from the trial of 945 patients, led by the Royal Marsden hospital in London, were published in the New England Journal of Medicine to coincide with the conference presentation.

Both ipilimumab, sold under the brand name Yervoy, and nivolumab were developed by an American biotech firm called Medarex, based in New Jersey and set up by a handful of immunologists from Dartmouth medical school. Their belief in immunotherapy for cancer has been amply rewarded – in 2009, their small company was bought by the pharma giant Bristol-Myers Squibb. The following year, Bristol-Myers Squibb announced the first major trial results of ipilimumab. Companies have been clambering over each other to get involved ever since.

Excitement over new cancer drugs is a dangerous thing. There have been melanoma drugs before that were greeted as miracle cures. These “targeted drugs”, the BRAF inhibitors, caused tumours to vanish completely. There was euphoria at cancer conferences. But within a few months, the disease came back with a vengeance and killed.

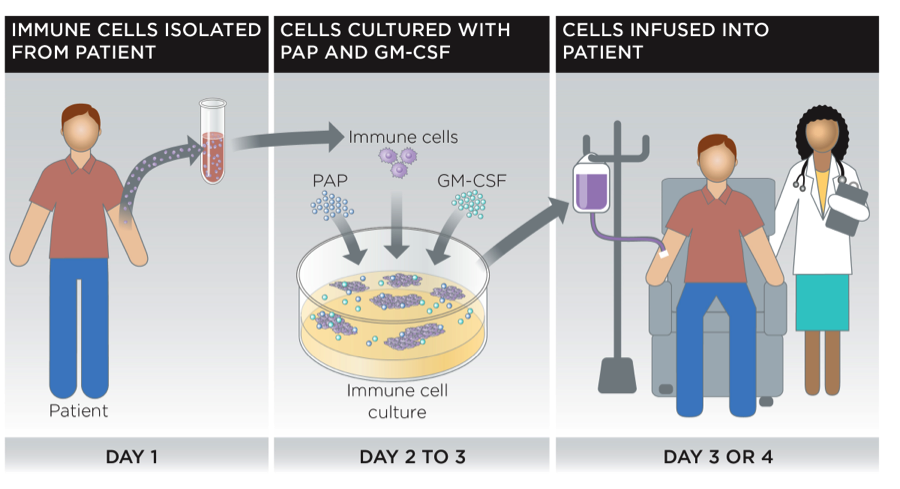

But the enthusiasm for immunotherapy may be better placed because this is a whole new way of tackling cancer. Scientists have long puzzled over the failure of the body’s own defensive immune system to attack cancer cells in the same way that it will fight a cold virus. They have discovered that cancer – just like the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that causes Aids – can hide from the T-cells that seek out and kill invaders. Cancer Research UK, which has been funding some of the research, says the cancer cells have developed a sort of “secret handshake” which persuades the T-cells not to attack.

In 1992, Japanese scientists discovered a molecule on the T-cells that was part of this secret handshake. They called it “programmed death 1” or PD1 and set out trying to disrupt it. The new drugs are the long-term result. They appear to work – at least for now – in advanced melanoma, which has a high death rate. Unlike other drugs, they are likely to work in a whole range of other cancers, too.

There are issues, as always. One is the likelihood of serious side effects. Dr Alan Worsley, from Cancer Research UK, said: “This research suggests that we could give a powerful one-two punch against advanced melanoma by combining immunotherapy treatments. Together these drugs could release the brakes on the immune system while blocking cancer’s ability to hide from it.

“But combining these treatments also increases the likelihood of potentially quite severe side effects. Identifying which patients are most likely to benefit will be key to bringing our best weapons to bear against the disease.”

Some patients have dropped out of the trials because of the side effects, which include feeling very sick. “Your immune system is designed normally not to attack your body’s own cells,” said Nell Barrie, of CRUK. “You have to boost the immune system beyond its normal function and you are going to sensitise the immune system. It’s very, very complex.”

The other big question will be how long the drugs will keep the cancers at bay. Most drugs for advanced cancers have delayed progression of the disease but not cured it. The immunotherapy drugs have not been used for long enough to be sure whether they will have a big impact on survival. But the big hope is that immunotherapy may be able to teach the body’s immune system to recognise and destroy cancer cells – and keep doing it so that the cancer is banished for good. And that is a truly exciting idea.

Ipilimumab was approved by Nice (the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) for advanced skin cancer patients in December 2012 in spite of the high cost of £75,000 for a four-dose treatment course, because Bristol-Myers Squibb agreed to give the Department of Health an acceptably sized discount. Nivolumab is likely to get its license this summer, which will allow patients outside the Royal Marsden’s clinical trial to have it, as long as a similar acceptable price can be negotiated with the company.

FRENCH VERSION