The blast shook buildings for miles around. Sleeping residents awoke, called each other, then stared at glowing screens, seeking an explanation for the explosion and the sirens wailing in the distance.

Last Thursday a massive car bomb had detonated outside a security building in Shubra Al-Khaima, a working-class district on Cairo’s northern edge. Chunks of concrete had been blasted off the building, shards of glass were sprinkled across the pavement. The windows of the neighbouring apartment building had been blown out, the private spaces of the families within flung open to the street.

Such incidents have become almost routine in Cairo. The Egyptian state is locked in battle with an accelerating insurgency. In June, Egypt’s chief prosecutor,Hisham Barakat, was assassinated in a bombing in an elite Cairo neighbourhood. Days later, insurgents staged a brazen attack on the military’s positions in north Sinai. Last week, Islamic State militants claimed to have beheaded a Croatian man who was abducted from a desert highway outside Cairo.

In response, the government drafted a draconian counter-terrorism law that establishes special courts and imposes fines on journalists who stray from the government’s account of an attack. Critics say the law grants sweeping powers to the president and could lead to an expansion of the government’s two-year-old campaign against political opponents.

Ordinary Egyptians find themselves wedged between the violence of the insurgents and a security state that wields unprecedented power.

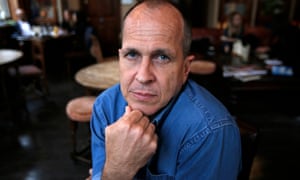

“I refer to it as the terror law because it’s not really anti-terror. It’s legitimising state terror,” said Wael Eskandar, an Egyptian journalist. “It’s a replacement for the emergency law, trumping the constitution and trumping people’s right to freedom of expression, and granting legalised impunity to police forces who are already very brutal.”

Egypt’s president, Abdel-Fatah al-Sisi, signed the new measure into law last Sunday. Sisi is the former military commander who led the forced removal of the elected Islamist president Mohamed Morsi in July 2013. Egypt currently has no parliament, and as a result legislative power rests in Sisi’s hands.

The legislation comes in the context of the two-year clampdown. Since Morsi’s removal, the state has accelerated the use of lethal force to suppress demonstrations, killing some 1,000 people in a single day in August 2013. In the crackdown, more than 40,000 people have been arrested, according to the Egyptian Centre for Economic and Social Rights.

Eskandar identifies with a generation of Egyptians who participated in the 2011 uprising that ended three decades of dictatorship under President Hosni Mubarak. It ejected Mubarak and his coterie from power and dismantled his political apparatus.

Millions of Egyptians hoped the revolution would go beyond merely a change of personnel to end the practices of authoritarian rule that characterised Mubarak’s regime: torture, corruption, electoral fraud. But since the 2013 military take- over, many of those same practices have returned and increased. Beyond the raw data of the political clampdown, activists say fear has crept back into Egyptian political life, a result of the re-emergence of a Mubarak-era security state.

“There was this culture of fear of criticising the government even under Mubarak, but now it feels even more real, where you know they might act upon it,” said Eskandar. “It feels like I’m under threat all the time. People I know are being threatened, being assaulted.”

The fear is a result of the possible consequences of running foul of the security services. Egyptian human rights defenders and activists have been jailed after farcical trials. Others have been banned from travelling. Still others face murkier fates. Esraa El-Taweel, a 23-year-old photojournalist, and two friends were reportedly arrested walking along the Nile cornice in Cairo’s Maadi neighbourhood on 1 June. For at least two weeks the authorities denied the three were in custody. Two weeks later Taweel was reportedly spotted in a prison.

Taweel is just one of dozens of people who have been “disappeared” recently by Egypt’s security forces, according to human rights groups. In early June a group called Freedom for the Brave identified 163 people who went missing over two months. The list included 64 people who were eventually located after spending more than 24 hours in undisclosed detention, 66 who were still missing, and other cases that were unverified.

In the new reality of a violent struggle between state and insurgents, journalists also face harassment and worse at the hands of the authorities. Reporting on the militants’ attacks has become a risky prospect, not least because of police who have come to regard people with cameras as suspect. After a bombing that destroyed part of the Italian consulate in Cairo in July, police held four journalists for arriving on the scene “too fast”.

In reporters’ encounters with police, the stakes are high. At least 18 journalists are in Egypt’s prisons, according to a tally released in June by the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists. On 29 August, a verdict is expected in a retrial of three journalists – Mohamed Fahmy, Baher Mohamed and Peter Greste – who spent more than 400 days in prison over their work with Al Jazeera English. Another, photojournalist Mahmoud Abu Zeid, known by the nickname Shawkan,has now been in prison for more than two years after attempting to document the August 2013 massacre in Cairo’s Rabaa Al-Adawiya Square.

“Their entire quest for power is built on a lie and they want to maintain that lie, so it’s really important for them that they’re not challenged,” said Eskandar. “So, for example, for international recognition they need to counter journalists who are reporting out of Egypt.”