A young boy is flogged in a public square. Onlookers shout “God is great.” Boko Haram militants shoot civilians in the heart and head, ignoring pleas of innocence and prayers.

The report below contains graphic images from secret Boko Haram videos obtained by VOA and 1st Afrika. The harsh violence may offend some viewers. It shows the reality and cruelty of life under Boko Haram’s rule.

In the northern Nigerian village of Kumshe, the terror group Boko Haram administered a violent and distorted version of Islamic law. Transgressions like wearing western-style clothing or getting a secular education carried extreme punishments. Purported drug dealers – such as the offenders shown in these videos – were sentenced to beatings and death.

Raw, unedited video of Boko Haram operating inside its territory in Nigeria is rare. The group is known for secrecy and carefully hides the identities of members and their whereabouts.

But VOA News obtained 18 hours of uncut videos in which the group recorded scenes of its own brutality. The images, from a Boko Haram laptop captured in a military raid, testify to the devastating suffering Nigerians endured under Boko Haram.

The execution of the men in the town of Kumshe, and other scenes showing Boko Haram members callously going about the daily business of their self-proclaimed caliphate are the subject of a VOA four-part video series, “Boko Haram: Terror Unmasked.”

The unedited recordings made little or no effort to hide the group’s most brutal acts. By all indications – time stamps on the videos, references by fighters, events described in news broadcasts heard in the background – the recordings were made in late 2014 and 2015, a period of expansion

Throughout its seven-year insurgency, Boko Haram has attacked government and civilian targets to win territory and instill fear across northern Nigeria. Leaders promise young foot soldiers martyrdom, conscripting them and sending them into battle lightly armed and with little training. The group has abducted thousands of women and children.

The videos recorded by Boko Haram chronicle one attack on a Nigerian army barracks in the town of Banki. Fighters gather in the morning, and leaders prep them to kill and be killed. The assault turns into chaos, with some militants begging for a gun.

Later, the Boko Haram fighters execute civilians in a nearby village after first interrogating them to find food and money. Boko Haram finances itself with kidnapping for ransom and with extortion and robbery, among other things.

Boko Haram’s campaign of violence has shattered lives, spread fear, displaced millions and destroyed the social order across northeastern Nigeria.

When the militants capture a village, interrogations follow. The goal: to extract information about the loyalties and whereabouts of loved ones who have fled.

Boko Haram’s purpose, as stated by its longtime leader, Abubakar Shekau, is to wage a holy war, ridding Nigeria of any western influences and creating a strict Islamic state. In practice, the group has shown little mercy for Nigerian Muslims, attacking mosques and majority-Muslim towns.

The Boko Haram video below shows leaders justifying killings and other atrocities based on their distorted religious ideology.

At a public tribunal, a messenger steps forward. He speaks for Abubakar Shekau, the Boko Haram leader in hiding, as militants prepare to execute two of their own.

The charge: homosexuality.

Boko Haram’s violent interpretation of Islam traces to the teachings of its founder, Mohammed Yusuf. Yusuf preached that western education was sinful. Tension between Nigerian authorities and the group escalated into deadly violence in 2009, when police cracked down on Yusuf’s followers and executed Yusuf in the street.

Shekau believes that attacking civilian targets, kidnapping schoolgirls and killing “unbelievers” – Muslims or not – are justified in the name of “jihad.” Religious scholars in Nigeria emphatically reject Boko Haram’s violent theology.

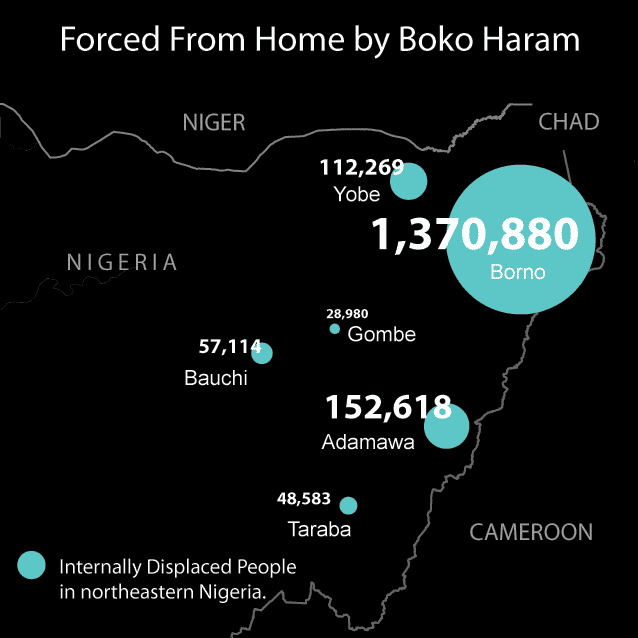

At its peak, Boko Haram controlled a territory twice the size of Belgium. The group’s occupation displaced more than 2 million Nigerians and has led to widespread food insecurity.

Today, many towns formerly under Boko Haram control have been liberated by the Nigerian military and neighboring states. VOA News traveled to northeast Nigeria in September 2016 to confirm military claims of improved security and see firsthand the human cost of Boko Haram’s insurgency.

Accompanied by a 12-truck military convoy outfitted with anti-aircraft guns, VOA visited cities once considered off limits and witnessed how Nigerians are attempting to rebuild. In areas not under military control, Boko Haram remains a threat. The group continues to launch suicide bombings and armed attacks on civilian and military targets.

Source: International Organization for Migration, Nigeria, December 2016