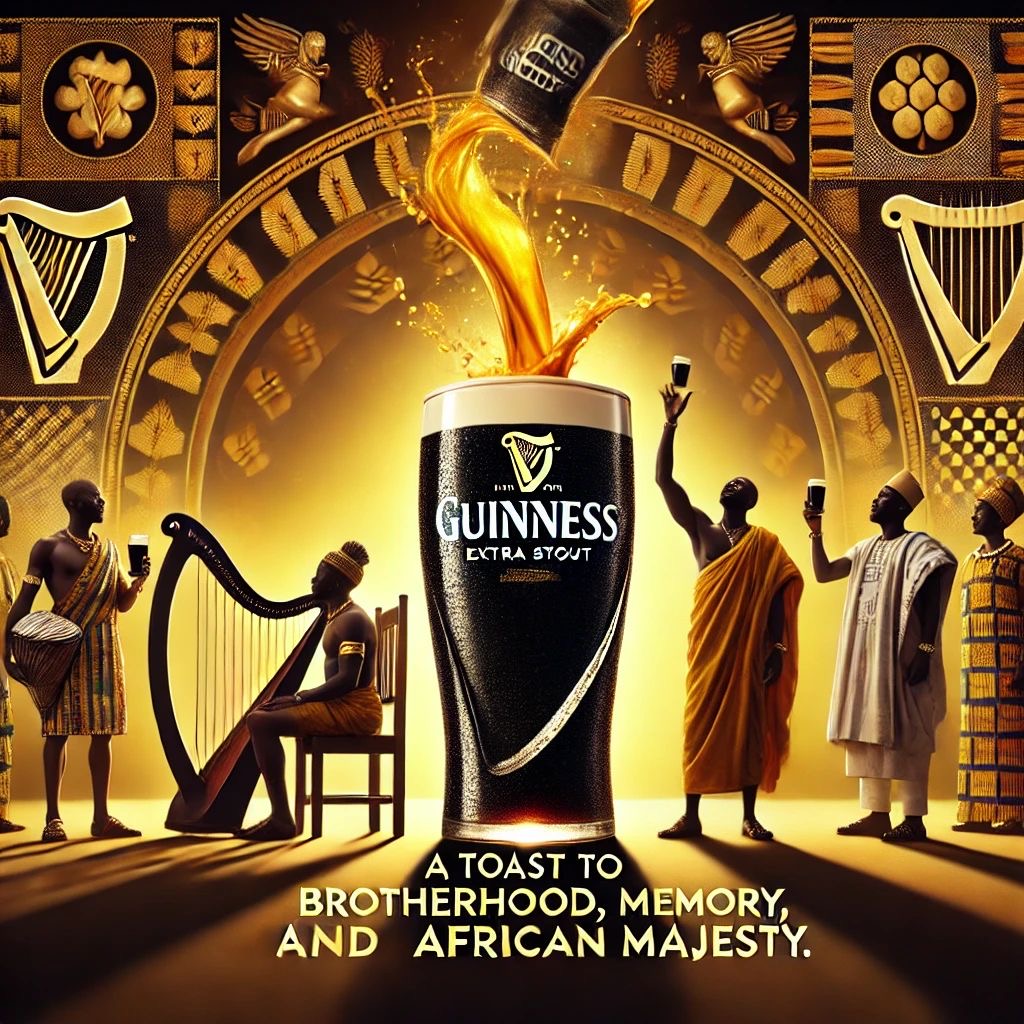

In the clinking of dark glass against sun-bronzed fingers, in the mellow pour of ink-black liquid into the heart of the gathering, there lies a ritual older than the bottle itself. Guinness Extra Stout, that bold, bittersweet emblem of fermented mastery, has transcended its Irish origin to become an icon of African identity, elegance, and emotional resonance. It is not just a drink—it is a symbol. A gesture. A mood. A communion. In many corners of Africa and across the diaspora, to hand a man a bottle of Extra Stout is to say, without words, “I see you. I honor you. You are kin.”

In the clinking of dark glass against sun-bronzed fingers, in the mellow pour of ink-black liquid into the heart of the gathering, there lies a ritual older than the bottle itself. Guinness Extra Stout, that bold, bittersweet emblem of fermented mastery, has transcended its Irish origin to become an icon of African identity, elegance, and emotional resonance. It is not just a drink—it is a symbol. A gesture. A mood. A communion. In many corners of Africa and across the diaspora, to hand a man a bottle of Extra Stout is to say, without words, “I see you. I honor you. You are kin.”

Among Africa’s elite class—from the weathered chieftains of Yoruba country to the sharply tailored statesmen in the streets of Kigali, from the griots of Bamako to the intellectuals in Johannesburg’s cafes—Guinness Extra Stout flows like black silk through time and occasion. It is not chosen out of chance or hype; it is revered. It exudes a rare duality: the rugged strength of ancestral labor and the refined allure of black-tie royalty. In boardrooms and bush bars alike, the presence of Guinness is a confirmation of status, memory, and gratitude—where wine may whisper, stout proclaims.

There is a reason the stout is called “Extra.” It’s more than just stronger; it carries weight, history, soul. Within its velvety bitterness lies the taste of aged patience and subtle pride. Africans do not merely sip it—they engage it. It is poured at naming ceremonies, placed beside the photos of the departed, held tightly in laughter-soaked reunions, and passed around in the silence of reflection when no words will do. It commands attention, invites storytelling, and wraps itself around memory like an ancestral cloth.

When an African elder accepts a bottle of Guinness, it’s not just a casual drink—it is the reenactment of generations who sat under moonlight to recount how far they’ve come. It is a nod to legacy, to survival, to dreams that refused to die. The bitter notes in the stout are not unpleasant—they are familiar, like the taste of hard-earned wisdom, like the ache behind old victories. In giving Guinness, one is not just offering refreshment but participating in a sacred exchange of respect and remembrance.

Across the diaspora—from Lagos to London, Accra to Atlanta, Nairobi to New York—Africans carry this ritual with them. In immigrant kitchens, at barbershop corners, in university dorms far from home, the bottle appears. It becomes a bridge between displacement and belonging, between cultural preservation and urban reinvention. Young men toast their fathers with it, and women of strength—queens in their own right—sip it slowly, reclaiming the spaces that once excluded them from ceremonial drink. It is not gendered, nor bound by class. It is universal in its African context: bold, resilient, black, and unforgettable.

Behaviorally, the presence of Guinness Extra Stout shifts the tone of any room. Where it sits, conversations deepen. Eyes soften. Stories unfold. It becomes easier to say “I love you,” “I forgive you,” “I remember you.” It slows time, not as intoxication, but as contemplation. This is why, even beyond Africa, to hand an African a bottle of Extra Stout is to perform an intimate act of recognition. It is a tribute to the dignity of blackness, to the depth of heritage, to the joy of resilience.

In African traditional circles, pouring libation with Guinness instead of palm wine or schnapps is no longer seen as dilution, but evolution. Acknowledging the past while embracing the present. It is now part of our rituals, our language, our texture. It speaks the grammar of unity.

So let it be known: to present a bottle of Guinness Extra Stout to an African man or woman is to offer more than a drink. It is to acknowledge the royalty in them, the journey in them, the beauty in their scars and laughter. In many African cultures, that gesture may hold more honor than offering a thousand-dollar bottle of champagne. Because in stout, there is story. In stout, there is spirit. In stout, there is home.

Long before the bottle is emptied, long after the last gulp has vanished into memory, what lingers is the feeling it created—a shared silence, a deep chuckle, a knowing look. That is the magic. That is the meaning.

Guinness is not just brewed. It is inherited.

And for those who know, for those who feel, for those who carry Africa in their bones—Guinness Extra Stout is not a drink. It is a crown.

By Jide Adesina

For 1stAfrika – Diaspora Culture and Society

©️2025 All Rights Reserved.