OPINION

One year after the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a pandemic in March of 2020, the spread of the virus remains unabated. In fact, some countries are now going through a second, and for others, a third wave of the pandemic.

The United States, a country recognized as one of the richest countries in the world and a paragon of scientific innovations and medical excellence is still paralyzed by the deadliest public health disaster since the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. According to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center, there are more than 29 million COVID-19 infections and deaths surpassing 540 thousand in a population of 330 million people. The trajectory of the case fatality rate (CFR) in the United States is a moving target riding on an incline. The same is true for countries in Europe, South America and other parts of Asia

For example, in most of the 48 countries in Europe, health care delivery systems are comparable to that of the United States. Europeans, on average, have €14,739 per-capita purchasing power, according to Growth from Knowledge (GfK), a global consultancy on data and analytics. Like the United States, COVID-19 burden is also on the upswing in Europe. There is now an easily transmissible variant of the virus in the UK, Italy and France. This may further increase the pressure on the estimated 37.7 million cases and over 880 thousand deaths so far in a total population of about 747.8 million in Europe.

By all objective public health and socio-economic measures, the continent of Africa should be a basket case in coping with the pandemic. Though rich in natural resources with a potential market of 1.3 billion people, most of the continent’s 57 countries have weak health care systems when compared to Western standards. According to the WHO, Africa bears more than 24 percent of the global disease burden, but only has access to about 3 percent of health workers with most countries having less than one doctor for every 1,000 people. In addition, most Africans live on less than $2 a day, according to The Brookings Institution, a nonprofit public policy organization based in Washington, DC. Communal living and the proliferation of densely populated slum communities within earshot of major metropolises in Africa, render social distancing nearly impractical. Add to that, political instability in places like Sudan, Ethiopia, Central African Republic, Mali, Ivory Coast and Libya, a coordinated public health response to a pandemic such as COVID-19 should be impossible. And yet the burden of COVID-19 is far less in Africa, compared to the most affluent regions of the world outside of Africa.

Well, assessing the pandemic reports and speaking to a noted expert on African affairs, revealed the following:

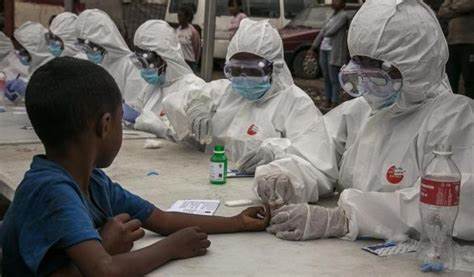

Public health leadership: African leaders and public health institutions have shown remarkable leadership and cognizance by putting in place measures, sometimes draconian, to control the spread of the virus. They closed airports, restricted internal travels, closed schools and religious worship services. Some countries like Ghana, Liberia, Namibia, South Africa and Nigeria imposed weeks-long lockdowns and curfews, and even used whips and arrests to disburse crowds during the lockdowns and curfews. Samuel Jackson, an African economist and author of “How a Pathogen Ruled the world” a book on the coronavirus and how COVID-19 exposed global inequalities within countries, attributes the experience with epidemics such as Ebola, HIV/AIDS, Measles and other tropical diseases, may have adequately prepared African governments to ably manage the pandemic. The incident management infrastructures from previous epidemics remained intact, like in countries like Liberia, afflicted by Ebola in 2014-2015, according to Jackson. That may have reduced the apprehension and efforts required to set up a new incident management infrastructure from scratch.

Before a single COVID-19 case was reported on the continent, a taskforce known as Africa Taskforce for Coronavirus (AFCOR) was set up by the Africa Centers for Disease Control (ACDC), a specialized technical institution established by the African Union to strengthen the capacity and support public health initiatives of Member States.

During the first wave of the pandemic, Liberia, one of three West African countries devastated by the Ebola epidemic in 2014, quarantined for 14 days all persons entering the country from coronavirus hot zones. Today, a PCR test or proof of a PCR test taken in the last 3 days, is required to enter or leave the country. Nigeria, the most populous country on the continent, requires proof of a PCR test on entry and another test on departure. South Africa also requires proof of a PCR test on entry and departure. Ghana requires a rapid antigen test on arrival and another test on departure. Ethiopia and Rwanda perform inquiry on history of exposure on entry. These measures, to a large extent, appear to have slowed the spread of coronavirus on the continent.

Low to limited COVID-19 testing regime: Testing provides a key measure of disease incidence. Though there are rigorous testing/screening regimes at various entry points to the continent, population testing or testing in communities is still very low compared to other regions. For example, of the more than 36 million tests performed to date on the continent, nine countries (South Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda and Zambia) account for about 70 percent of testing, according to data analyzed from Worldmeter, a global coronavirus data repository. The remaining 48 countries have only performed about 11 million tests in a population of about 737.5 million people or 1,513 tests per 100,000 people.

Limited access to healthcare services: The distribution of hospitals and other healthcare facilities in most African countries is not adequate to meet the care needs of the population. Locations of the few facilities that are available present challenging barriers in the form of long travel times and transport cost. On average, it takes between 2 to 5 hours in travel time to get to the nearest hospital or healthcare facility, according to a study by Dr. Pascal Geldsetzer of the Department of Medicine at Stanford University and his colleagues, published in The Lancet. Long travel times, coupled with poor roads in rural areas, discourage physical access to healthcare facilities. As a result, people needing healthcare attention may resort to traditional or herbal remedies. A COVID-19 infection, for example, could easily be interpreted as malaria, an endemic disease in Sub-Saharan Africa, with signs and symptoms (fever, headaches, body aches, loss of the sense of taste and loss of appetite) almost similar to COVID-19’s. Walking 2 hours one way to the nearest healthcare facility in rural areas where an illness can be properly diagnosed becomes an insurmountable challenge. Local remedies for malaria and related diseases are instead administered thus undercounting what could be a possible COVID-19 case.

Youthful population: The Brooking Institution’s Africa Growth Initiative estimates that more than 60 percent of Africa’s population is under the age of 25 years. Only 6 percent of the population is 60 years and older. In a research published in Nature Medicine, only 21 percent of persons ages 10 to 19 infected with COVID-19 exhibit clinical symptoms. That means, 79 percent of teenagers infected with COVID-19 are asymptomatic. If we generalize these findings to the African population, it means many people in Africa could be infected and spreading COVID-19 without knowing it. This could reflect why the number of cases is lower in Africa compared to other regions.

Given the factors assessed above, there could yet be a hidden phenomenon that is responsible for the low level of coronavirus cases in Africa. A further examination will be required to understand this phenomenon.

Taiyee N. Quenneh, PhD.,